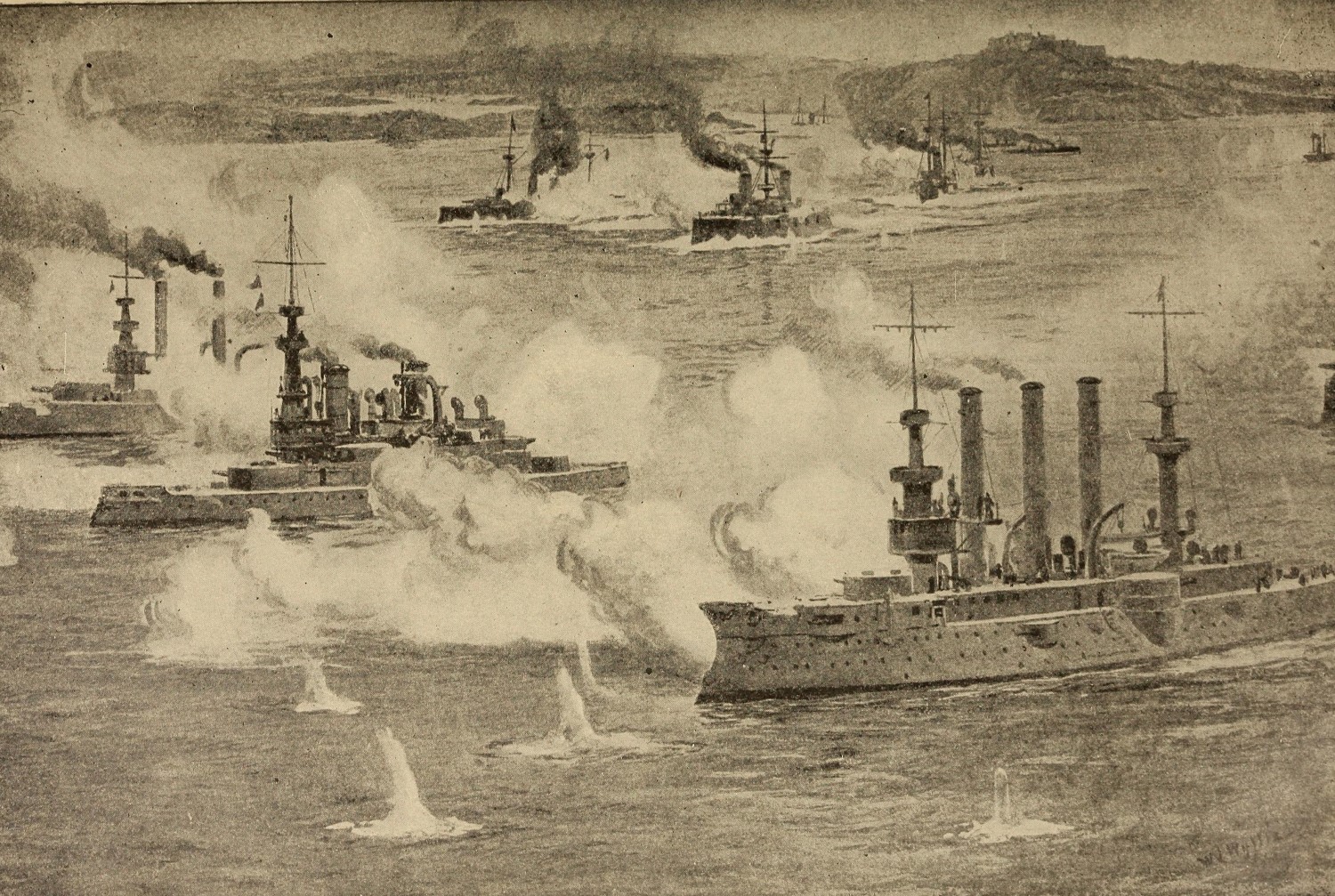

In 1898, tensions between the US and Spain over the remains of Spain's Caribbean empire boiled over after the battleship Maine blew up in Havana Harbor. The US declared war and blockaded Cuba, while the Asiatic Fleet under George Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet in the Philippines at Manila Bay. The Spanish dispatched a fleet under Admiral Cervera to break the blockade, but it ended up trapped in Santiago on Cuba's south coast. The Americans landed troops and tightened their blockade, and on Sunday, July 3rd, Cervera finally sortied. Three of his cruisers were destroyed almost immediately, while the last one survived less than four hours. The Spanish lost almost 20% of their men, while the Americans had a single sailor killed and minor damage to their ships.

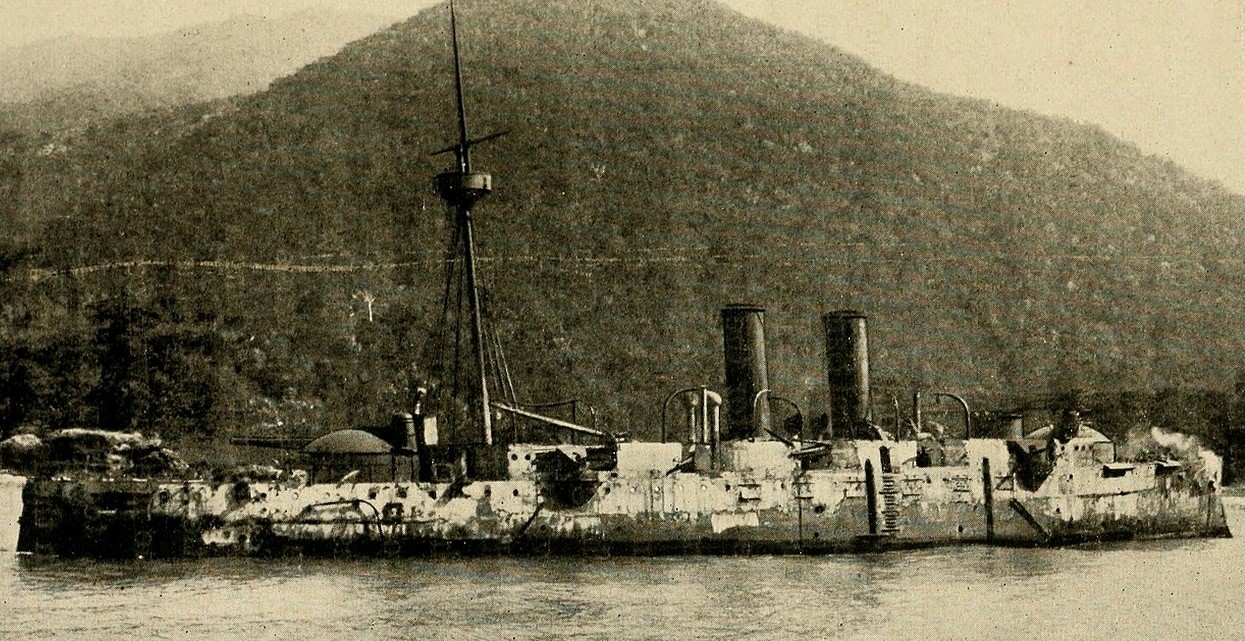

But what explains this one-sided victory? Unlike Manila Bay, the answer is not found in overwhelming superiority on the part of the American ships. The Spanish cruisers were reasonably modern, and while they had some technical issues, particularly with the 14cm guns, these alone cannot explain their failure to inflict any meaningful damage on the Americans. The most badly-damaged American ship, Brooklyn, took only four hits from medium-caliber (4"-6") guns and another 16 from lighter guns, mostly 6 pdr and 1 pdr.1 The best explanation probably lies in the ability of the Americans to establish fire superiority over the Spanish at the beginning of the battle. This is best seen in Gloucester's victory over the Spanish destroyers, where rapid and accurate gunfire drove the gunners from their posts and prevented any meaningful retaliation. Most of the guns, particularly the lighter ones, were mounted in the open, and the hail of American fire drove many Spanish gunners from their posts and hindered the accuracy of those who stayed.2

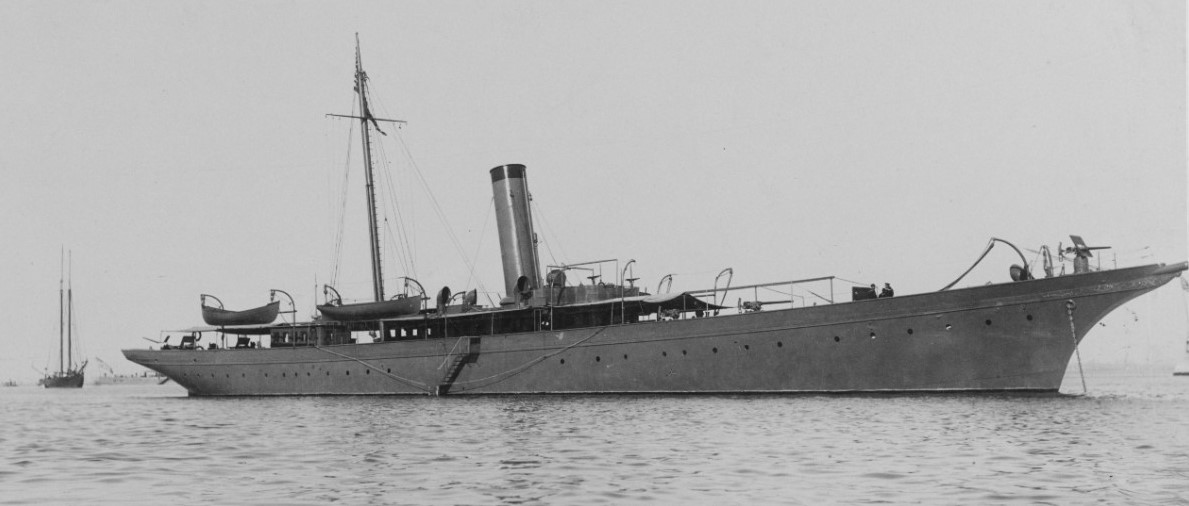

USS Gloucester

An interesting parallel can be drawn between the experience of the Spanish at Santiago and Jackie Fisher's maxim "Hit first! Hit hard! Keep on hitting!!" Before WWI, many believed that the first side to start hitting, or even straddling the target, would gain a major advantage not only in the direct damage done but also in the disruption of the enemy's gunfire. A high rate of fire and early hits were not only offensive measures, but also defensive ones. This thinking led, among other things, to the British stuffing their battlecruisers with extra ammunition, a policy that ended in tragedy at Jutland. Two main factors probably explain why such tactics were so much more effective at Santiago than they were during WWI.3 First, the Spanish at Santiago were suffering from serious morale problems, which neither side faced two decades later.4 Second, the decade after 1898 saw more and more of a ship's firepower move from the traditional model of men working a gun in an open or lightly-protected position to men under heavy armor working machinery. The hoist operator on a 12" turret can't really see the effects of battle unless the shell actually penetrates the turret, while an ammunition passer for a 6" QF gun might see the guy next to him killed and decide he'd rather take shelter.

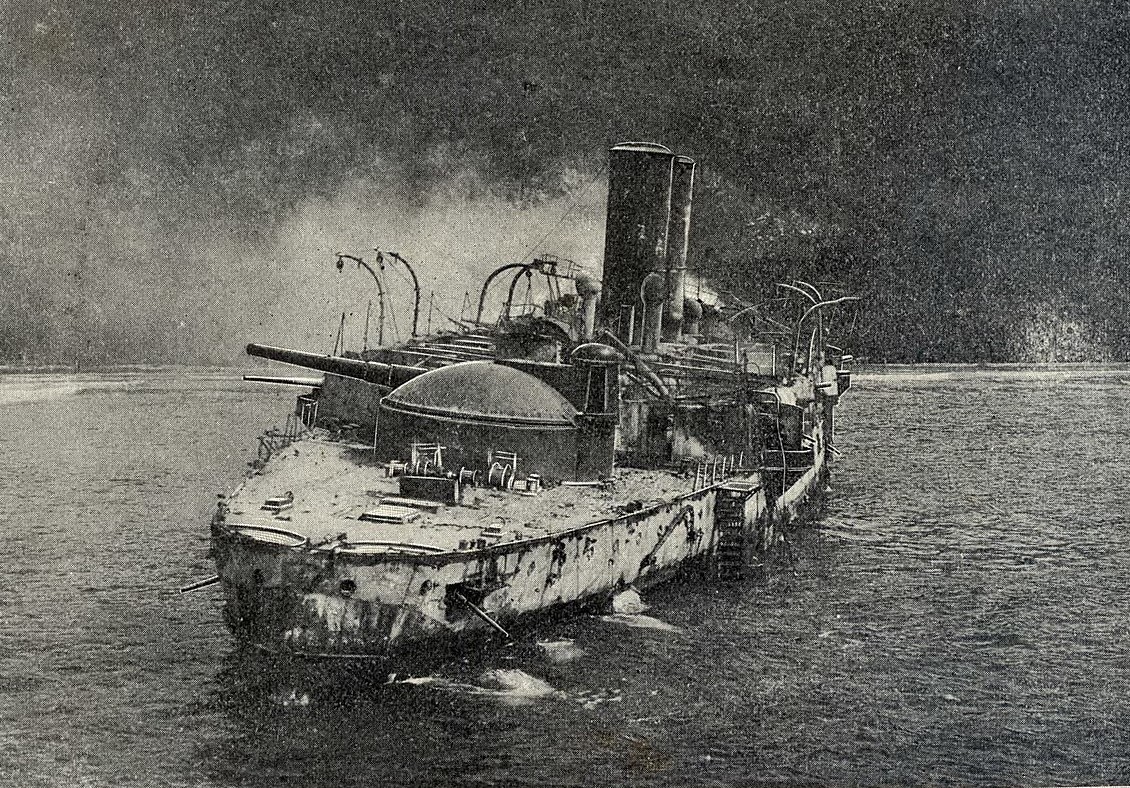

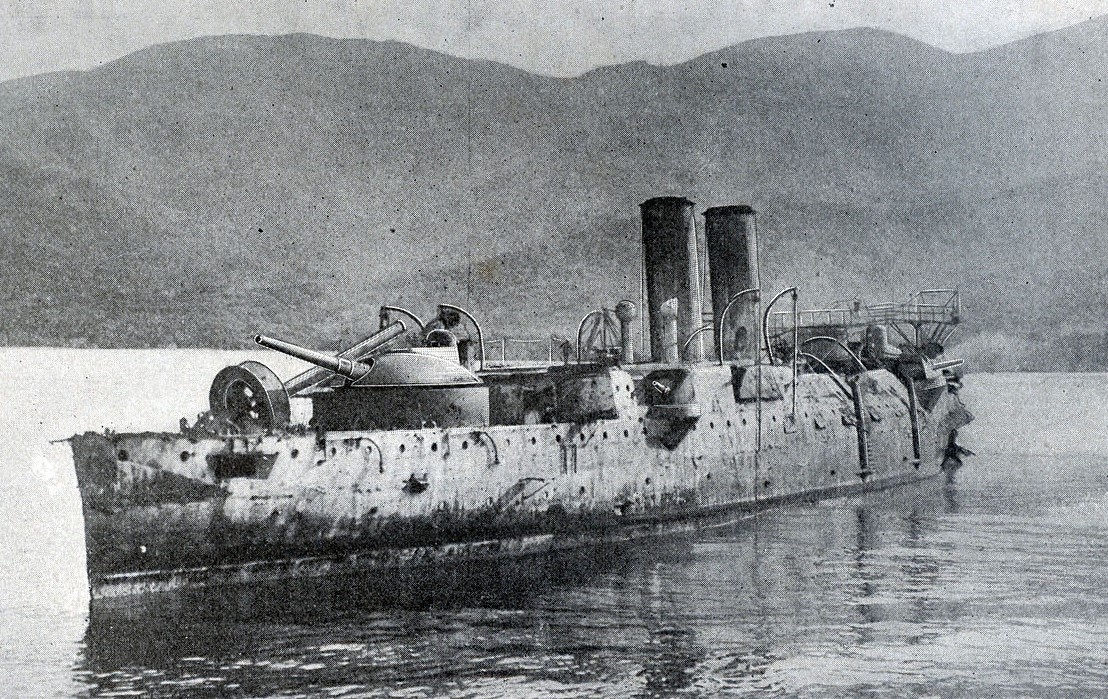

The wreck of Vizcaya. Note that the wooden weather deck, which would be overhead, has been burned away.

An examination of American gunnery makes the results even more surprising, as the Spanish were disabled by a small number of hits. Teresa took only 10 hits from guns 4" and above, while Vizcaya and Oquendo took 14 each.5 Less than 3% of American shells hit the target,6 a value significantly lower than would have been predicted by looking at the target practice results. Longer range and the stress and smoke of battle explain some of this, but the situation still did not do a great deal of credit to the American gunners, particularly when compared to the Japanese three years earlier. But the Spanish deserve even less credit, as a comparison to the performance of Zhenyuan at Yalu River makes clear. The Chinese battleship, despite having many of the same personnel problems as the Spanish, had 464 holes in her when inspected after the battle, and she was still able to fight. In partial fairness, she was a battleship, and much better armored than the Spanish cruisers, but it appears that the biggest difference is the extensive use of wood on the Spanish ships and their lack of firefighting capability after the mains were damaged.

The wreck of Almirante Oquendo

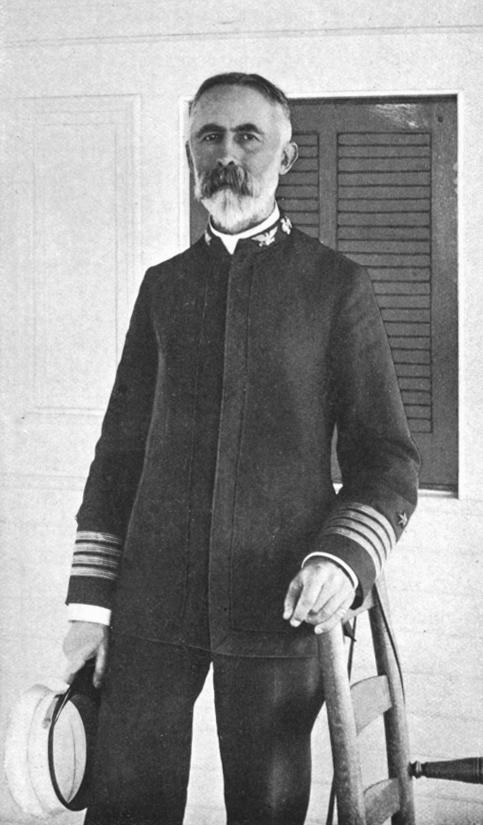

But the hardest-fought and most bitter phase of the battle was still to come when the smoke cleared. There was almost immediate controversy over which admiral, Sampson or Schley, deserved credit for the victory, and this quickly built into a public furor rivaling that between Jellicoe and Beatty over Jutland. Sampson had been in overall command of the fleet, and the plan for the blockade had been his, but he had been absent at the critical moment, leaving the fleet in Schley's hands during the chase. There was already bad blood between the two men, as Schley had been ahead of Sampson on the USN's seniority list before the war,7 but the junior man had been promoted over him and given the command. As soon as the battle was over, Sampson sent messages to Washington claiming complete credit for the victory and not mentioning Schley at all.

William Sampson

Soon, the naval officer corps was divided into Schleyite and Sampsonite factions, the Sampsonites, lead by Mahan, claiming that Sampson's plan had been the key to victory, and that Schley's actions, particularly his dithering while trying to find Cervera and the order for Brooklyn to turn away from the enemy, revealed him to be cowardly and ineffective. Schley's advocates, joined by the majority of the popular press, viewed his command during the battle as the most important factor. Things got worse when permanent promotions were given to both officers, placing Sampson 2nd behind George Dewey on the navy list, with Schley 3rd. In November 1899, the Secretary of the Navy, fed up with the feud, ordered an end to public discussions of the matter by naval officers. This was unsuccessful in quieting the controversy, and in 1901, Schley himself requested a court of inquiry to clear his name. The court's results were mostly a victory for Sampson, although Dewey, the President of the court, submitted a minority opinion in favor of Schley. Schley appealed to President Roosevelt, who again told everyone to stop the dispute, and it finally died down, although it didn't really end until after Sampson and Schley died in 1902 and 1911 respectively.

Infanta Maria Teresa

So what do I make of all of this? I have to come down mostly on Sampson's side. Any reasonably competent officer in Schley's place should have been able to win the victory he did, and his only really notable order during the battle was to turn Brooklyn away from the Spanish. This is an understandable decision, as Brooklyn was the weakest of the big American ships, but also the only one that could, in theory, keep up with the enemy cruisers, so preserving it was obviously a priority. But Schley could not have won without a well-trained fleet, ready to swing into action in minutes and positioned so that it could intercept the Spanish when they sortied. And the credit for that rests primarily with Sampson, absent though he may have been during the actual action.

Vizcaya

The destruction of Cervera's fleet dealt the death-blow to Spanish hopes in the New World. The American ships were now uncontested masters of the Caribbean, with only light units now required to enforce the blockade and support the rebels still fighting for control of most of the island. The garrison of Santiago surrendered two weeks after the battle, bringing the Cuban land campaign to an end. Only Puero Rico remained as a major Spanish bastion, and it was there that American attention would turn next.

1 My primary source for this series, The Downfall of Spain, counts these weapons for rounds fired and hits, and generally treats them as meaningful parts of the ship's battery. This is slightly puzzling to us today, but at the time, so much of a ship's equipment was exposed that they were probably useful weapons at the short ranges of the day. ⇑

2 Several guns retrieved from the wrecks had their sights set for ranges over 10,000 yards, while the longest actual combat was around 6,000. This neatly explains why so many Spanish shells were overs, but it's hard to see why they were set that way in the first place. ⇑

3 While the Germans hit first at Jutland instead of the British, the "hit first" effect is mostly absent throughout the war, regardless of who was doing the hitting. ⇑

4 This might not have been the case if the High Seas Fleet had made one last sortie. ⇑

5 The 8" gun came out of the battle looking very good, although this had more to do with the lack of proper 6" QF guns on the American ships. As a result, the US battleships planned after 1898 mostly had 8" batteries as well as smaller guns. ⇑

6 It does bear pointing out that some shells may have left no mark, as they hit wood which was then consumed by fire, and others may have not been counted because the areas they hit were submerged when the ship sank. Hits on the destroyers were also not able to be counted because they sank, while the denominator in the calculation was the total number of shells fired. ⇑

7 For reasons that I don't understand, the USN continued the policy of promoting on the strict basis of seniority, except in time of war, until sometime around 1910. ⇑

Comments

The Chinese battleship, despite having many of the same personnel problems as the Spanish, had 464 holes in her when inspected after the battle, and she was still able to fight.

I, personally, would have been much more ready to surrender to the Americans than to the Japanese.

That's a good point as applied to Colon. Less so to the other three ships, which were hors de combat very early on.

@doctorpat - Maybe? AFAIK the Japanese had not yet earned a reputation for barbarity at this early stage, with the Port Arthur Massacre and the occupation of Formosa still in the future.

Wasn't this soon after the Battle of Pungdo where the Japanese fleet shot up the Chinese lifeboats after the Chinese ship sank?

I'd think that the Chinese sailors would have less trust in Japanese good treatment than the Spanish would have towards the Americans. Though I could be making my judgement based in hindsight.

A typo: "a minority opinion in favor of Schely."