By 1956, the British Empire was crumbling. They had left India almost a decade earlier, removing the main rationale for their control over the Suez Canal, but the growing dependence of Europe on Middle Eastern oil had made Suez more important than ever. But British actions in Egypt had left a lot of bitterness, bitterness that was exploited by Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had risen to power in a coup. Anthony Eden, the British Prime Minister, had become obsessed with Nasser, and when Nasser nationalized the Canal in July, Eden ordered plans drawn up for military action.

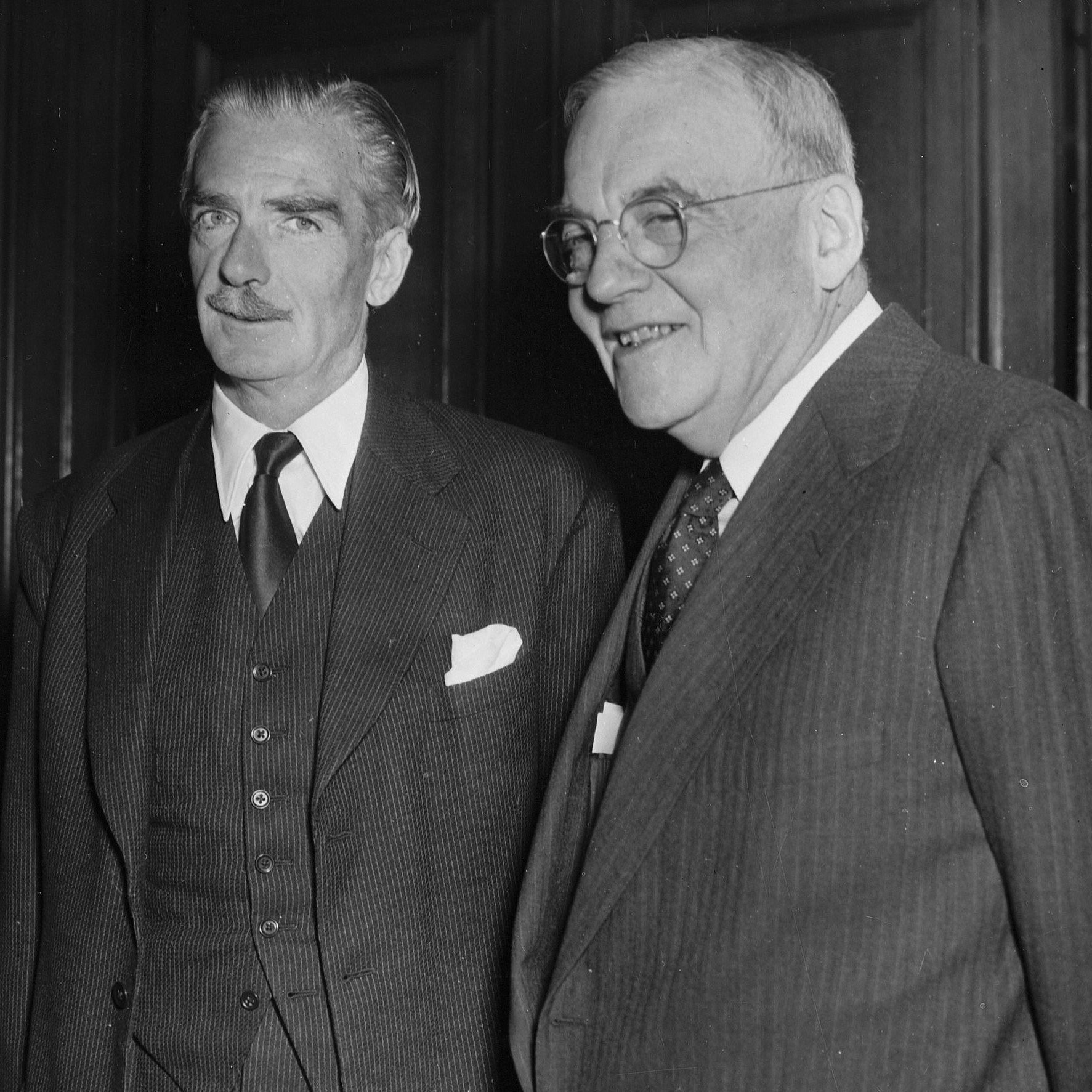

Anthony Eden and John Foster Dulles

The French, whose private investors still held a major stake in the Canal, were quick to sign on, and both nations believed the Egyptians would be unable to safely operate the Canal without the Suez Company's skilled pilots and technical know-how. Unfortunately, the most important member of the western powers, the United States, was not onboard with the plan to invade, and Eisenhower sent Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to try and head off military action. But Eden was determined, stung by charges of "appeasement" from MPs who well remembered the failure of British diplomacy in the years before Hitler invaded Poland.1

There were two other major factors at play as the Suez issue heated up. The first was tension between Israel and Egypt, dating back to the 1948-1949 war that had seen Israel established. The Egyptians still smarted from their defeat, and the need to avoid being seen even tacitly accepting the existence of Israel was a major driver of the actions of leaders throughout the region. The British and Americans had tried to dampen the conflict by limiting arms sales to Egypt, but the arrival of Soviet weapons convinced Israel that the Egyptians would attack once they had mastered the new hardware, a belief furthered by obvious preparations on Nasser's part for war and an ongoing series of raids and counter-raids across the border. A secondary issue was the status of the Straits of Tiran, which should have given Israel an outlet onto the Red Sea, but which Egypt had closed in retaliation for Israeli reprisals for guerilla raids.

The aftermath of an Israeli counter-raid

The second factor was the upcoming Presidential election in the US. Eisenhower, seeking a second term, very much did not want a war, and he and Dulles made it clear that the US would only countenance peaceful solutions to the problem. This prompted Nasser to reject a proposal to put the Canal under international control, which in turn increased the strength of the Anglo-French case for military action. Dulles would have none of it, and repeatedly came up with schemes that looked like they would be used to pressure Egypt, brought the Europeans into them, then revealed that they were in fact nothing of the sort. The Egyptians helped him by being surprisingly willing to work towards a reasonable settlement, although Eden thought Nasser would renege and continued to push for war.

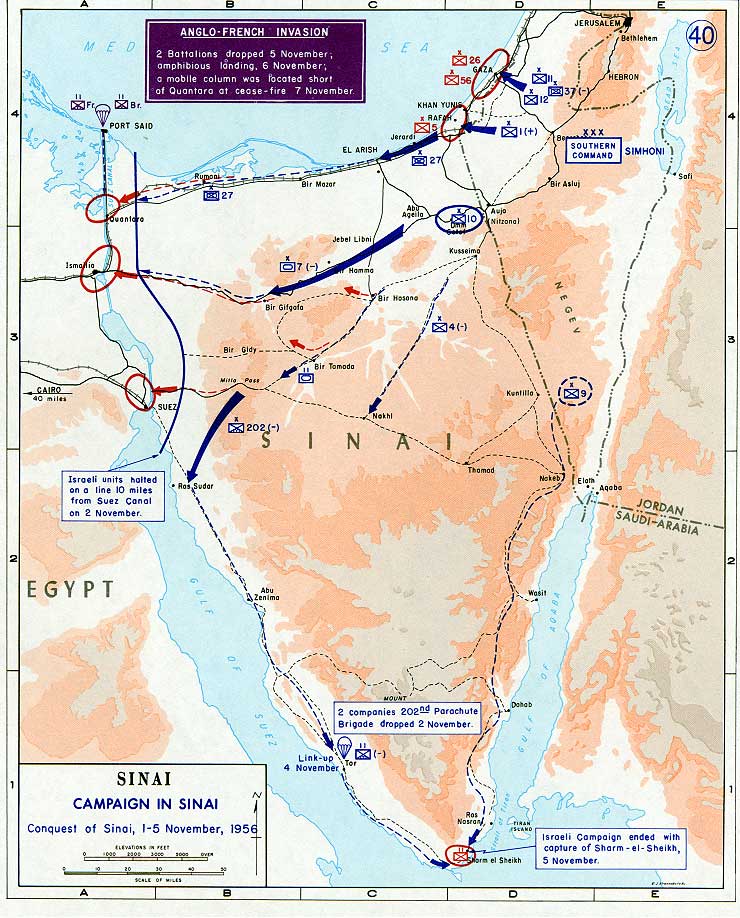

Matters finally came to a head in mid-October, three months after Nasser took control of the Canal, at a meeting at Chequers, the British Prime Minister's country residence. The French, who thought Nasser was the critical backer of the revolt they were facing in Algeria, suggested that they attack Egypt in concert with Israel, which would end the threat to France's African colonies and show the nation's resolve in the aftermath of their recent defeat in Indochina. The British, concerned about what this would do to their "informal empire" in places like Iraq and Jordan, came up with a modification. Israel would invade the Sinai on its own, prompting Britain and France to "intervene" and take control of the Canal to "separate the combatants". The French had been backing Israel and serving as its main weapons supplier to distract Nasser, so it was easy to bring them onboard, and the Israelis were delighted to be able to preemptively take out the Egyptian Army.

Egyptian Il-28

Eden was delighted by this plan and quickly agreed, with the main sticking point being strikes against the Egyptian Air Force, which had recently taken delivery of Il-28 bombers from the Soviets. The Israelis wanted them taken out before they invaded, something only Britain, operating from bases in Cyprus, could do. Eden thought that a preemptive strike was impossible, but agreed to issue an ultimatum that would expire only 12 hours after the start of hostilities. The Israelis were unhappy with this, but agreed to the proposal in a secret meeting at Sèvres, France. The entire matter was kept to only a handful of senior ministers and civil servants in each nation, with Eden telling the broader Cabinet only of a plan to intervene to protect the Canal in case the Israelis attacked. The US could see the activation of reservists (largely to backfill units withdrawn from NATO duties) and the movement of military forces into the eastern Mediterranean, but was apparently in the dark about the specifics of the plan. Oh, and the international situation was complicated not only by the looming election in the US, but also by the outbreak of turmoil in Hungary, where revolutionaries sought to break away from the Soviet bloc.

The basic plan for the Anglo-Franco-Israeli attack

The military plan, dubbed Operation Musketeer,2 had undergone substantial evolution while the diplomatic angle was being worked on. The initial plan had been a lightning seizure of the Canal Zone itself by parachute assault, although neither Britain nor France had appropriate airborne forces trained and ready, as the task of policing their declining empires had stretched things very thin. Work began on getting them ready just after the seizure of the Canal, but it was clear that a bigger assault would be needed, and a lot of very muddled planning ensued, where it wasn't clear what Britain and France wanted to accomplish, or how their efforts would bring about any objectives they would have. The initial plan was to secure Alexandria, with its excellent harbor, then push to the Canal Zone, hopefully deposing Nasser along the way, but the required force to fight across the Nile Delta and the addition of Israel to the plan meant that the objective was changed back to the Canal itself, where the Anglo-French force could make a claim that it was intervening to protect the vital waterway with a straight face. If that wasn't enough, they could push on to Cairo, using a total of 50,000 British and 30,000 French troops. Before the invasion, which was now a combined airborne-amphibious operation, the Egyptians would be subjected to several days of intense aerial bombardment while the ships moved east from Malta, which some within the RAF thought would break them entirely and render the ground assault unnecessary.

A Centurion tank on a low loader

The military plan itself was relatively sensible, though badly handicapped by the low state of readiness of both nations, which resulted in such exciting problems as not being able to move the planned armor contingent to the embarkation ports in time because the British Army had sold off most of its tank transporters and the commercial moving company hired worked to union rules. The diplomatic plan, on the other hand, was conducted in an air of unreality that was usually found only in the planning rooms of Imperial Japan. The assumption that an attack on the Canal Zone would lead to Nasser's overthrow was dubious at best, as the Arabs, both at home and abroad, were more likely to rally behind him in the face of what they would see as an obvious extension of European colonialism. More concrete was the situation with Britain's allies in the Arab world, most notably Jordan, where British troops were actually stationed to protect the country.3 If Israel attacked Jordan as well as Egypt, then there was even a possibility that the British and Americans could end up facing off against each other. And the fact that one or both superpowers might oppose the operation to avoid antagonizing the Arabs didn't even seem to have crossed the minds of the planners in London or Paris. Instead, they pushed ahead with military operations, which we will look at next time.

1 There's at least a colorable argument that British diplomacy didn't really fail, and that appeasement was less a matter of "hopefully we can buy off Hitler" and more "hopefully we can buy enough time to rearm before war breaks out". But this is a fairly recent development in historical understanding, and the former was how everyone saw it in 1956. Also, the recent regime change in Iran gave Eden the confidence to try something similar in Egypt. ⇑

2 A word picked because it was the same in English and French. The initial name had been Hannibal, but that is often spelled Annibal in French, so it had to be changed. ⇑

3 In fact, Britain had armored units stationed in both Libya and Jordan, but thought it impossible to use them against Egypt for obvious diplomatic reasons. ⇑

Comments

A long time ago, I read one a book that was simultaneously one of the most fascinating, and most boring, books of all time: The Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich by William Shirer. It had all kinds of fascinating things in it.

Shirer had access to all kinds of internal Nazi Party documents, and the book is extremely well-sourced. And one thing that really surprised me in reading that book, is that in the 1930s, Germany did not want to go to war with Britain, and in fact believed that Britain might end up being an ally. They had planned for Britain to stay neutral in all of their military adventures, with a sort of "they'll leave the continent alone, since they have an ocean to protect them" mentality.

With this in mind.... FROM BRITAIN'S PERSPECTIVE, appeasement WOULD HAVE WORKED if Britain had stayed out of World War 2. Obviously, this would have some rather extreme downsides. But the point is, none of those downsides would have hit Britain.

So, in a sense, British Appeasement actually worked, in terms of serving British interests.

Press X to doubt. It might have worked in the short run, but a Nazi Germany that had subjugated the whole of Europe could have easily outbuilt Britain in a naval arms race, at which point the ocean would no longer have been much of a barrier.

Britain viewed the emergence of a European hegemon as an existential threat for centuries, and for good reason.

I'm with Humphrey on this one. Not only was Britain always nervous about a European hegemon, but whoever is running Europe is going to be inherently nervous about Britain sitting there astride their trade routes. The choices for Britain were fight alongside France in 1939, or fight on their own later. And in that frame, the right choice is obvious.

(I'm not saying that Hitler wasn't saying "wouldn't it be great not to have a war with Britain". He absolutely was. But that just proves that he was an idiot when it came to strategy, which we already knew.)

It is well explained in Yes Minister.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVYqB0uTKlE

No there isn't, all the delay did was buy time for Hitler to rearm.

There's quite a bit of scholarship that would disagree with you. Hitler was running ahead of Britain in a number of areas, and the year or two bought with appeasement made a significant difference. To pick the easiest example to check, the Bf 109 was introduced in Feb 1937, the Hurricane in December of that year and the Spitfire in August 1938, a month before Munich. The extra year meant a lot more Spitfires in service when war broke out relative to Bf 109s.

The big question is how much of this was policy.

Thanks for this series Bean.

Just a side note. Anthony Eden spoke French quite well. I have watched an interview with him that was conducted solely in French.

The reason I mention this is I wonder if he was consulting with the French in French. My guess is that most likely he had an expert interpreter on hand for those times he might have needed something clarified.

My understanding is that it's very common for meetings between political leaders with different first languages to be conducted via interpreter, even when one party is fluent in the other's language, both to avoid miscommunications and to give people time to think.

There is a ton of scholarship on the diplomatic aspects of the crisis, and I'm sure that there's a PhD thesis somewhere on that. I am minimizing that in favor of looking more at the military side, which is covered poorly if at all in most sources.