The Suez Canal is one of the world’s vital transport links, cutting thousands of miles off the trip between Europe and East Asia. In 1956, Egyptian dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the canal, enraging the British and French, who had owned it and depended on it for their oil. Diplomatic attempts to regain control of the Canal failed, and they began to conspire with Israel to stage a war between Israel and Egypt, which the European powers would then “intervene” in, giving them an excuse to recapture the canal and humiliate Nasser. Unfortunately, this failed to take into account such minor factors as Arab public opinion, the opposition of the United States and the likely response of the Soviets.

Ariel Sharon (left) with his paratroopers

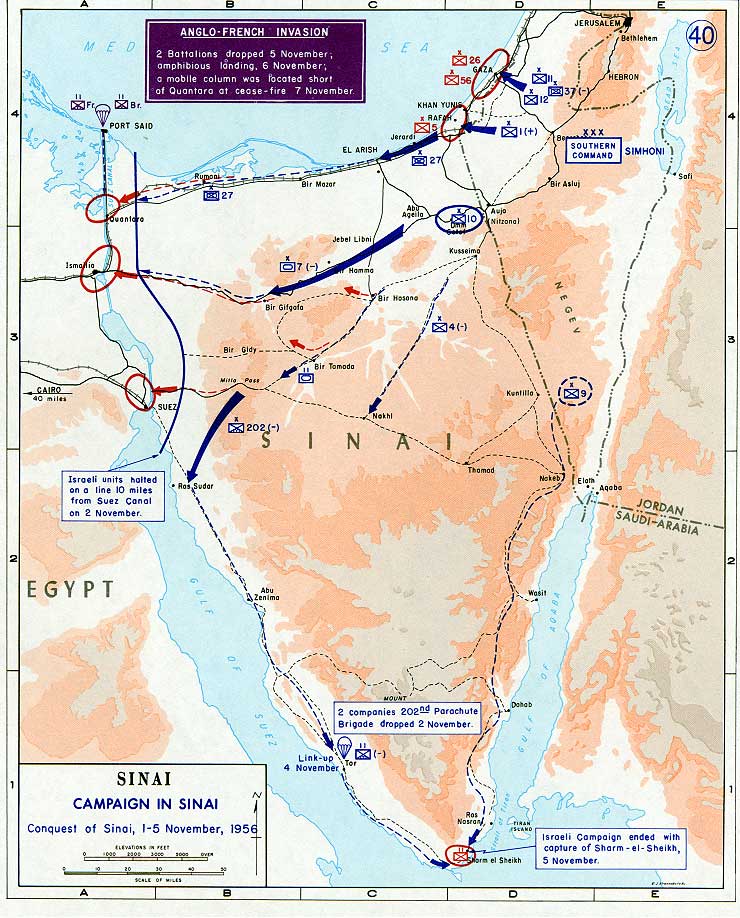

Things kicked off on October 29th, 1956, with Israel citing terrorist attacks out of the Egyptian-controlled Gaza Strip as the reason for its invasion.1 A deception plan intended to make it look like they were about to attack Jordan had worked, and the Egyptians, and the rest of the world, were taken by surprise, to the point that they weren’t even sure it was a real attack and not another reprisal operation for about 24 hours. P-51 Mustangs were dispatched to cut Egyptian telephone wires with their wings and propellers, sowing confusion in the face of a three-pronged Israeli attack. In the south, the 9th Infantry Brigade seized Ras an-Naqb on the Gulf of Aqaba, infiltrating through rough terrain to bypass Egyptian positions, while the 4th Infantry Brigade struck al-Qusaymah in the north, opening the way to attack Egyptian positions in Gaza and northern Sinai. Both of these were at least in part to secure the flanks of the main action, a thrust through the central Sinai by the 202nd Paratroop Brigade, under the command of an officer named Ariel Sharon. Most of his men would walk or ride, but a battalion was dropped on Mitla Pass, two-thirds of the way across the peninsula, in an attempt to secure the chokepoint before the Egyptians could respond, and to make the threat to the Canal credible as part of the pretext for Anglo-French intervention. Unfortunately, a navigational error placed them several miles from their objective, and they dug in on the east side of the pass instead of the western end, while Sharon’s plans to reach Mitla within 24 hours fell victim to inadequate transport. In the end, he would arrive in the evening of October 30th, a creditable performance given that three Egyptian strongpoints had to be overrun in the process and they were faced with Egyptian air attacks.2

The basic plan for the Anglo-Franco-Israeli attack

On October 31st, things heated up both at Mitla and in the north. Because of the navigation error during the initial drop, the paratroopers were dug in on bad ground to the east of the pass, and Egyptian troops had begun to probe the Israeli position. Sharon wanted to push into the pass, where his light units would have better defensive positions, but his orders were to stay put. He solved this problem by requesting permission to reconnoiter the pass, which aerial reconnaissance indicated was empty, but sent in two companies with tank support. Unfortunately, the aerial photos were wrong, and the force ran straight into an ambush which kept it pinned for seven hours, facing not only machine-gun fire but also repeated air attacks. Finally, darkness fell, and Sharon sent in another force which descended from the tops of the cliffs. In the small-unit actions that followed, the Israelis routed the Egyptians, killing over 200 for the loss of only 38 men. Despite this, the incident remained a controversial one throughout Sharon’s career, as the seizure of the pass was strategically unnecessary.

An Egyptian tank destroyer knocked out by the Israelis

In the north, the fall of al-Qusaymah had opened the route to the main Egyptian defensive position in the area, the so-called “hedgehog” just to the southwest of the Gaza Strip. It was a strong position, laid out by ex-German officers in the early 50s, but fairly lightly held, as the Egyptian forces had been drawn down to reduce tensions with Israel and minimize the number of men caught west of the Canal if war broke out with the European powers. The commander had assumed that the main threat would come from the east, but on the 30th, the Israeli 7th Armored Brigade found a pass that allowed them to flank the position, opening it to attack from the west as well. Despite this, the Egyptians held out through heavy fighting until the predawn hours of the 2nd, when they withdrew, afraid of being cut off. But this was minor compared to the scale of Egyptian troops trapped in the Gaza Strip, where the Israelis had managed to breach the minefields around Rafah on the 31st. By noon the next day, they had seized all of the road junctions, isolating the Egyptians to the north, who surrendered after an attack on the 2nd.

A column advances on Sharm el-Sheikh

The defeat of the Egyptian forces in and around Gaza cleared the way for armored thrusts to the west, continuing the fiction that the Canal was menaced by the fighting. The Egyptian units that had been ordered into the area were promptly withdrawn, presumably to face the Anglo-French attack that now appeared imminent. The final drama of the Israeli portion of the war would play out in the far south of the peninsula, where the 9th Infantry Brigade began a long march down the coast of the Gulf of Aqaba, with the intent of taking Sharm el-Sheikh and opening the Straits of Tirian. The route was normally a camel track, and the Israeli soldiers struggled to get their lighter vehicles through the steep ridges and deep sand, while their tanks were transported by landing craft that had been sent from Haifa to Eilat by road and rail. The brigade finally reached the outer defenses of Sharm el-Sheikh on November 4th, only to find them abandoned, at least in part thanks to a drop of some units of the 202nd Parachute Brigade to the west, which prompted the Egyptian commander to pull his forces in on the town itself. The Israeli assault on the heavily-fortified town the next day got off to a bad start, with the first push chopped up by heavy Egyptian fire, but the defenders promptly collapsed, bringing the war in Suez to an end with their surrender at 9:30 AM on November 5th.

Ibrahim el-Awal under tow

The Israeli-Egyptian conflict was not solely fought on land. The only naval action of note came on October 30th, when the Egyptian destroyer Ibrahim el-Awal attempted to shell the industry around Haifa. A French destroyer on patrol nearby attempted to intervene, but was unable to prevent 160 4″ shells falling on the city. Two Israeli destroyers, Eilat3 and Yaffo, set off in pursuit, and as they were a few knots faster than the Hunt-class Ibrahim el-Awal, they hauled her in after a few hours. Their greater firepower soon told, and after a couple of Israeli fighters joined in with rockets, the Egyptians abandoned ship. Despite the damage, Ibrahim el-Awal was intact below the waterline, and after a boarding party tugs were soon dispatched to bring her into Haifa. She was eventually commissioned as INS Haifa, serving under the flag of Israel until 1968. In the air, the Israelis, despite being outnumbered at the start of the war, quickly gained air superiority over Sinai. They appear to have shot down between 7 and 9 Egyptian planes with the loss of one in air-to-air combat and another 10 to ground fire. That said, the IAF’s free hand wasn’t always an unalloyed good thing from the perspective of the soldiers on the ground, as target identification is hard and air strikes proved almost as dangerous to the people they were supposed to be supporting as it was to the defenders. The reason for their superiority can be found partially in Egyptian incompetence and lack of pilots, but mostly because the British and French intervention gave them more important problems to deal with, like a lack of airplanes, as we will see next time.

1 Nasser had actually been working to bring the incursions under control to avoid having to fight Israel while he was in a confrontation with Britain and France. ⇑

2 This is to the credit of the Egyptian Air Force, which had only 30 pilots for the 150 MiGs it had received from the Soviet Union, as well as some Vampires, but still managed to fly 40 sorties on the 30th and 90 on the 31st, losing 4 fighters without claiming any kills. ⇑

3 Which would gain some prominence a decade later. ⇑

Recent Comments