Popular perception is that the battleship of WWII was useless, supplanted by the aircraft carrier and kept around merely because of hidebound admirals. The idea dates back to the 1920s, when Billy Mitchell began his PR campaign in favor of the air services. Some date its obsolescence back to that point, others cite the lessons of WWII to prove the malign influence of the "Gun Club" on naval procurement. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. The battleship had a vital role to play in the fleets of WWII, and even for a few years thereafter, and the Allied Navies in particular did a good job of balancing their fleets for the threats they faced.

Missouri under air attack

The basic argument against the battleship is that it was far too vulnerable to air attack, and that resources would have been better spent on carriers. And on the face of it, there's some logic behind this. Aircraft were indeed the largest killer of battleships, despite not being a threat until WWII. But the carrier's use of aircraft was a double-edged sword. It could only be effective in conditions that allowed it to operate its aircraft, which pretty much ruled out operations at night1 or in bad weather. If a surface ship managed to get within gun range, either by taking advantage of one of these conditions or via sheer luck, the consequences for what was essentially a big box of fuel and ammunition could be catastrophic.

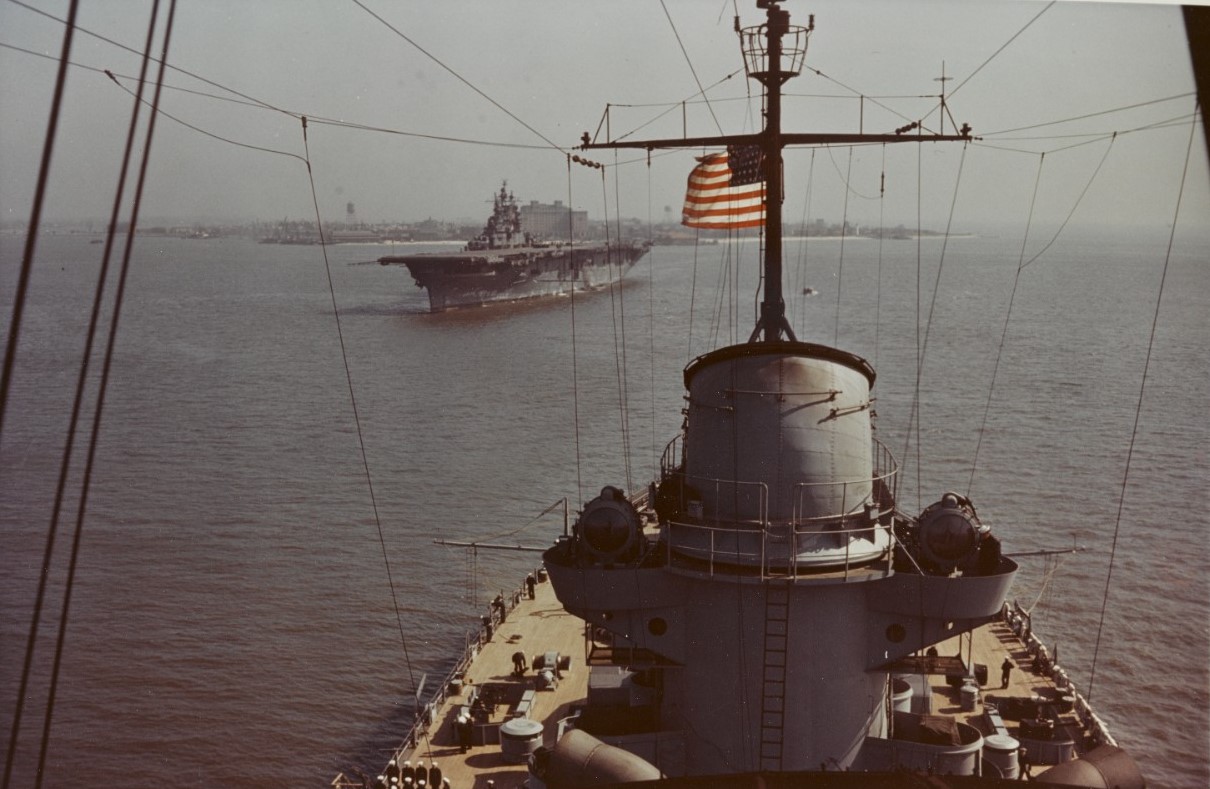

Lexington from Spot One aboard Iowa, 1943

This was obviously of major concern to navies, and both the US and Japan fitted their early carriers with 8" guns explicitly to deal with surface threats. However, this was obviously not the solution (the whole "box of fuel and ammunition" thing) and it soon became common for a carrier to be escorted by several of the new treaty cruisers. Later, as battleship building resumed, the need to keep up with the carriers played an important role in the design of first the North Carolina and then the Iowa classes. This arrangement continued during the war, and although it was never tested properly against surface ships, the battleships and cruisers played a vital role in screening the carriers from air attack.

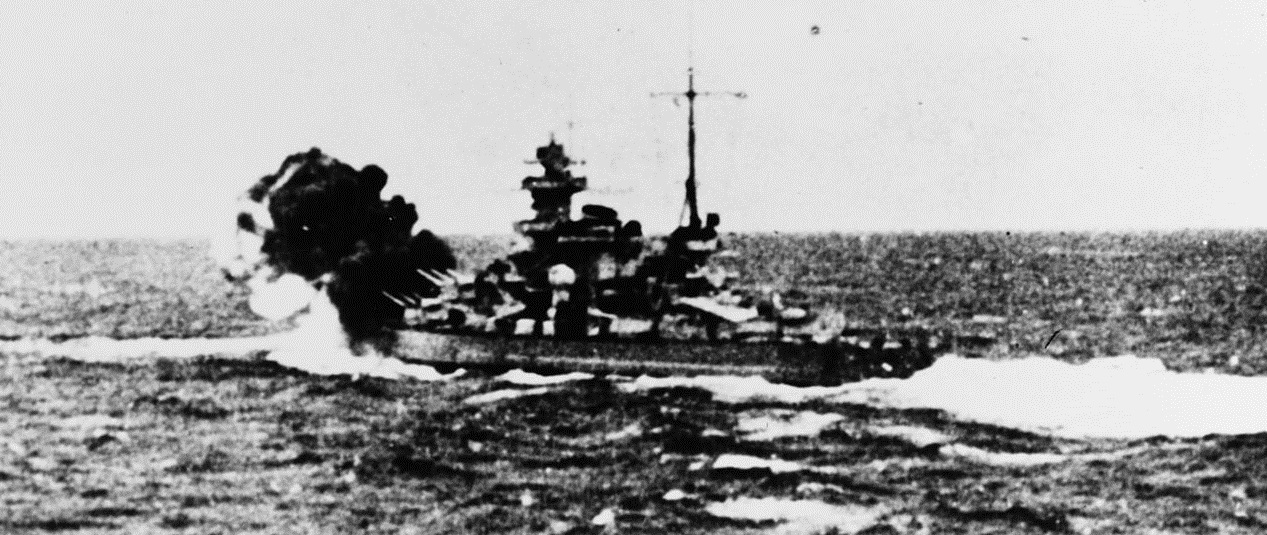

Scharnhorst firing on Glorious

Carriers only ended up within gun range of enemy battleships twice during the war. The first time was when Scharnhorst and Gneisenau caught HMS Glorious while she was aiding the evacuation of Norway. She was escorted by only two destroyers and was not flying patrols or otherwise on alert for surface threats, and all three ships were sunk by the German battleships. Four years later, an American escort carrier group by the name of Taffy 3 found itself staring down most of the Japanese battle line off Samar in the Philippines. The six carriers were protected by only three destroyers and four destroyer escorts, and the Japanese should have been able to overwhelm the entire group much more easily than Glorious had been sunk. This wasn't the case, and Samar is instead remembered as perhaps the most illustrious action in the history of the US Navy, with only one of the carriers, Gambier Bay, sunk by gunfire while the escorts managed to actually drive off the massively superior Japanese force.

Shells fall around Gambier Bay

But how did battleships fare under air attack? Most people cite Pearl Harbor as signalling the end of the battleship era, but this makes little sense when examined closely. All of the battleships in question were stationary or moving very slowly (as was the case at Taranto earlier) and were not buttoned up for action. If the carriers had been in port, they would have suffered exactly the same fate, and with no more ability to defend themselves. If we restrict our sample to only ships that were at sea and thus able to defend themselves, we find that only five battleships were sunk by air attack,2 while four fell to other capital ships,3 three to smaller surface ships4 and two to submarines.5 And even the five ships sunk by air attack provide a good view of some of the limitations of air power against battleships.

Prince of Wales (top) and Repulse under attack

We'll start with Repulse and Prince of Wales, sunk on December 10th off Malaya while attempting to counter the Japanese attack on Singapore. 85 Japanese land-based level and torpedo bombers attacked the two ships while they believed they were out of range. The first torpedo attack was fatal for Prince of Wales, as the single hit bent one of her shafts, flooding the engineering spaces and throwing the electrical system into chaos. Repulse, skillfully handled, avoided several torpedo attacks before the Japanese managed to trick her captain and land a hit amidships. Even this wasn't immediately fatal, as she could still make 25 kts, but Prince of Wales took three more hits during the same attack. The Japanese then focused on Repulse, and three more torpedo hits sent her to the bottom. Prince of Wales followed an hour or so later. This was by far the best performance of aircraft against battleships at sea. 49 torpedoes were launched for 8 hits, and both ships had relatively ineffective torpedo defense systems. Repulse was a WWI-era battlecruiser that had only been lightly modernized, while Prince of Wales had several serious design flaws. Other battleships would have done significantly better in the face of these attacks.

Musashi under air attack

By far the hardest of the ships to sink was Musashi, sunk the day before Samar. The Americans had expected the Japanese to interfere with their landings at Leyte Gulf, and had in fact detected the Japanese force that ultimately attacked Taffy 3 the previous day. They had 5 fleet carriers and 5 light carriers within range, with a total of about 600 planes onboard, while the Japanese force had five battleships and seven heavy cruisers. The Americans were only able to put about 259 sorties over the Japanese fleet, about half of which were dive and torpedo bombers. They zeroed in on Musashi, hitting her with 19 torpedoes and 17 bombs before she succumbed. Unfortunately, their concentration on that ship meant that while Yamato and Nagato each took two bomb hits and heavy cruiser Myoko suffered enough torpedo damage to send her home, the Japanese still had four battleships and six cruisers off Samar.6 Even the largest carrier force the world had ever seen couldn't put enough weapons on target to actually defeat the Japanese battleships.

Yamato during her last sortie

It was Yamato's turn six months later, when the Japanese sent her on a one-way sortie to interfere with the American invasion of Okinawa. This time, the Americans sent 386 planes against the Japanese battleship, a light cruiser and eight destroyers. Both of the larger ships and half of the destroyer contingent were sunk, but it took 13 torpedoes7 and at least 8 bombs to put the battleship under.8 Nor did the Americans treat this as a foregone conclusion. They assembled a force of six older battleships, seven cruisers and 21 destroyers from the ships protecting the landing and providing fire support, with the intention of protecting the landing beaches in case Yamato made it through the air attacks.

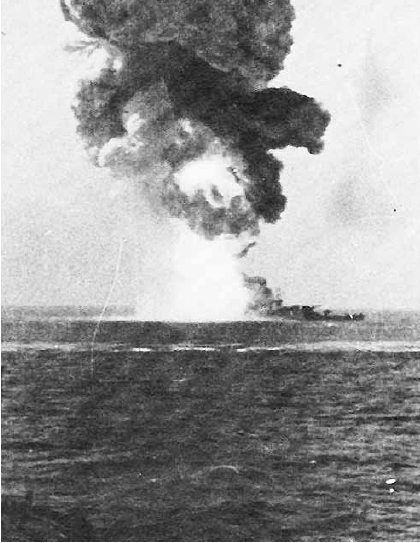

Roma blowing up

That just leaves Roma, the only one of the ships to be sunk by a small attacking force. Six German Do 217's loaded with Fritz-X guided bombs attacked the Italian fleet fleeing in advance of the armistice between Italy and the Allies. Two of the bombs hit Roma, the first doing serious damage to her engines and the second setting off her forward magazine, destroying the ship instantly. A third hit on her sister Italia did some damage, but not enough to cripple the ship.

The sort of carrier power required to reliably sink battleships

The point of all of this is that battleships are remarkably durable things, and barring bad luck, take a lot of punishment to sink, which in turn requires a lot of airplanes. Roma alone succumbed to a small number of aircraft, and they were land-based bombers carrying a unique weapon that proved much less successful later on. But even Repulse and Prince of Wales required at least two carrier wings worth of aircraft between them,9 while Yamato and Musashi required far more than that. It's also worth pointing out that none of the battleships sunk by air attack had more than minimal air cover.10 For that matter, I've focused on battleships sunk by air attack simply because it would be far too difficult to chronicle all of the battleships that survived air attack. But the consequences of allowing a battleship within range of your carriers are all too clear. Both times it happened, it didn't end well for the carriers, and it really should have ended a lot worse off Samar than it actually did.

So was the decision to build more battleships in the late 30s a mistake? No. Simply put, the big guns of the battleship were the last, best argument of naval warfare until the early 50s.11 Planes could be grounded by darkness or bad weather. Inadequate scouting could let the enemy slip ships into gun range. Destroyer torpedoes might miss or run out. Navies could never rule out the threat of an enemy warship appearing over the horizon from the bridge of a carrier, and a fast battleship was the best possible counter. We also cannot overlook the uncertainty that the men making these decisions operated in. As a 1936 Parliamentary sub-committee looking into proposals that Britain stop building battleships said, "If their theories turn out well founded, we have wasted money; if ill founded, we would, in putting them to the test, have lost the Empire."

1 Night carrier operations began during WWII, but even the US never took it past a few special carriers, barely able to provide CAP and scouting during the hours of darkness. It wasn't until the 50s that it became a standard part of carrier practice. ⇑

2 Prince of Wales, Repulse, Roma, Musashi and Yamato. ⇑

3 Hood, Bismarck, Kirishima and Scharnhorst. ⇑

4 Hiei, Fuso and Yamashiro, with the last being in conjunction with capital ship gunfire. ⇑

5 Barham and Kongo. ⇑

6 For those wondering why the Americans didn't know it was coming, the Japanese briefly turned back, which was misinterpreted as turning for home, and limited night scouting meant that their true course wasn't detected. ⇑

7 It's worth pointing out that 131 torpedo bombers flew missions against the Japanese force, and the light cruiser Yahagi took 7 torpedo hits, so the hit rate was only about 15%, even with the Americans at the end of the war. ⇑

8 One of the major reasons that Yamato took so many fewer torpedoes than her sister was that the pilots had all been instructed to make torpedo attacks from the port side, instead of hitting both sides as they had in 1944. ⇑

9 Yes, a typical carrier wing was ~90 planes, but about half were fighters, which wouldn't usually contribute much to sinking capital ships. ⇑

10 The Japanese did attempt to provide fighters during Leyte Gulf, but the Americans never saw more than maybe 4 at a time, and simply shot them down. ⇑

11 Battleships went away slightly earlier because the Soviets had nothing bigger than cruisers themselves. The two major changes that took place in the early 50s were the development of all-weather carrier aviation and the deployment of nuclear-tipped SAMs, which had a secondary anti-ship function. ⇑

Comments

I don't really disagree, but I feel inclined to gesture vaguely in the direction of the Bismark. Like yes it was scuttled rather than directly sunk by enemy action and artillery damage played a role, but it was effectively mission kill by a handful of biplanes.

So in the spirt of asking bean to do more work I am curious how these numbers stack up against carriers, both in terms of hits and sorties against required to sink. My impression is that they are much softer targets, but I'm curious if that's simply a function of the higher emphasis placed on sinking them.

Bismarck is a dubious counterexample - yes, a handful of Swordfish dealt what amounted to a mission kill at the time, but on the other hand, that was a spectacularly lucky shot (at least as lucky as the critical hit on Hood), and Bismarck probably could have recovered from that if not for being run down by battleships.

@megasilverfist

I'd say you should fight me over Bismarck being scuttled, but you have swords and I don't. Practically speaking, she was sunk by the British. There was no reason to scuttle her, except as part of the process of abandoning ship, because she was going down soon. Also, torpedoes from the British.

As Jade says, the aerial torpedo was both a spectacularly lucky hit and probably survivable if the battleships hadn't shown up. Also worth pointing out that PoW's shell hit played a part in the mission kill.

@Chuck

There is no doubt that carriers are softer targets, particularly against bombs. Examples: Lexington took two bombs and two torpedoes, and exploded after gas vapor leaked from the fuel system. Yorktown was essentially killed by three bombs and two torpedoes. Hornet was three bombs and a torpedo. Akagi was one bomb, Kaga four, Soryu three and Hiryu four. The big issue in pretty much all cases was fire.

I’m just now working my way through Toll’s Twilight of the Gods and just now read this passage, about the beginning of the Yamato’s passage through the SB strait:

“Steaming again to the east, the Center Force passed a few miles south of the smoking, listing, foundering wreck of the Musashi. As one of the two most heavily armored ships in the world, she could take a great deal of punishment, and she had—more than twenty bomb hits topside, and about nineteen or twenty torpedoes below the waterline, including fifteen in her port side. No warship in history had ever suffered such punishment and survived.”

To be fair, there are carriers and carriers. The US sort of assumed that that carriers couldn't be adequately protected (certainly not while meeting treaty limits) and built them to hit first and hard. The British Illustrious class had 3" flight deck armour, which while by no means battleship grade, enabled the class to survive bomb hits of over 2,000lb, and shrug off many lighter hits.

On the one hand, all the battleships sunk by aircraft had crap AA. Most were crap by the standard of their day, and they were all extremely crap by the standard of 1945. this should strengthen your argument, late war radar guided VT shells were extremely deadly.

That said, I don't think I'm convinced. Even the iowas had virtually no ability to force decisive results on a carrier, while an essex could reliably mission kill an iowa pretty reliably.

@cassander

I'm not arguing for the primacy of the battleship over the aircraft carrier. I'm arguing that it was still an important part of the fleet during WWII, and a lot less vulnerable than commonly thought. I may have spent too much time on the second half of that to get the full message across.

@Alexander

Yes, but look at Okinawa. The British took as many kamikaze hits as the US carriers, despite having a lot fewer ships. The sacrifice in air group really wasn't worth it. Also, they had a lot fewer pitched carrier battles than the Americans or Japanese.

@Alexander: Notwithstanding their armored flight decks, both Illustrious and Indomitable were mission-killed by a handful of ~1000 lb bomb hits from the equivalent of a carrier air wing's worth of Stukas. And I don't think either had a real torpedo defense system, though fortunately there was only a single torpedo hit between them.

Even the RN recognized that the Illustrious-class, with their woefully undersized air groups, weren't really suited for Pacific-style carrier battles - that's why they leaned so hard into night operations, as their own version of trying to get the first hit in despite their inability to contest the skies. Of course there are some obvious difficulties inherent in being exclusively a night-fighting force, that can't risk being spotted by the enemy in daylight, and some of the limitations of RN carrier doctrine showed up pretty clearly during Somerville's attempt to ambush the Indian Ocean Raid (where if Nagumo had paid attention at all, I suspect the whole "unsinkable armored carrier" meme would have died in April 1942).

The British carriers certainly weren't 'invincible', and had issues with their air wing, partially due to a lack of hanger space, though operating without a deck park accounts for a lot of the difference. Relying on Fulmars for air defence because of a heavy focus on night operations made dealing with land based single seaters tricky, though this was largely resolved (with USN help) before Okinawa. Arguably they were lucky, but I think that they are a good example of carriers that were by no means soft targets.

Speaking of armor on carriers, given how battles actually played out, did the belt armor on US fleet carriers actually make any sense?

Meaning, basically, why build armored ships, if nukes will kill them anyway, right? But isn't that oversimplified?

Armor and a strong hull means the nuke has to hit much closer. Or be much bigger, but IIRC blast damage scales with the inverse cube of distance.

So you'd need a precision attack, bomber in the 60s or missiles later. Which can all be shot down, especially if nuclear SAMs are allowed.

And anyway, the question isn't whether battleships are vulnerable to nukes, it's whether they're more vulnerable than other ships while securing sea control. The point being that battleships went away because the open oceans were firmly under US control, and the only serious enemy didn't even try to do more than denial.

And now I'm hoping for a "battleships vs nukes" post.

@Alexander - Even in 1945, operating with deck parks in the Pacific, the Illustrious-class air groups were still pretty anemic by USN (or IJN for that matter) standards. The armor made them small, cramped ships for their tonnage, qualities which are particularly unhelpful for operating aircraft. And as bean mentioned, at Okinawa their small air groups meant they took a disproportionate number of hits, especially given their placement well away from the primary threat axis.

"Soft" vs. "hard" targets are relative, and by the standards of "twenty thousand ton warships," the Illustrious class were still pretty soft. Armor meant to protect against 500 lb bombs was a lot less effective against weapons two or four times that size, and didn't help at all against hits that bypassed the armor entirely, notably including torpedoes.

The Talos and Terrier SAMs (and their Soviet equivalents) were designed to defeat single aircraft targets with conventional warheads, which is plenty accurate against ships, and were fast enough that no 1950s-vintage SAM was going to be much use against them with any warhead. Once those are in service, any guided-missile cruiser can insta-kill any surface target within its radar horizon once nuclear release is authorized. And in the 1950s, it was assumed that nuclear release would be authorized for any conflict worth sending a battleship.

At that point, not much value for battleships except shows of force and shore bombardment against non-nuclear powers.

@Jade

Never got tested, but it's probably a good idea to harden your carriers at least a little so a destroyer can't turn one into a pyre with a few 5" shells. Belt armor just isn't that heavy compared to decks. I think the ratio is usually 6 or 7 to 1 for a given thickness.

@Alex

Pretty much what John said. Battleships are a little bit harder than unarmored ships against nukes, but not nearly enough to compensate for the sheer killing power of nuclear weapons. My nuclear bomb slide rule shows that the warhead on a Talos would only have to get within about a half-mile to hit 10 psi overpressure (the USN's target for hardening stuff like antennas), and at that range, everyone onboard is dead in two weeks from radiation (assuming no protection, but even battleship armor isn't that effective against high-energy X-rays).

Nuclear weapons at sea - effects is coming along, but slowly.

@Philistine Roughly what was the difference in air group between an Illustrious and a Yorktown? How much air power do you have to give up to be able to resist the sort of hit that crippled the Franklin, a more modern post treaty design (https://www.navalgazing.net/OCallahan-and-the-Franklin)?

@Alexander

It was originally 36, expanded to 54 by the end of the war. Yorktown-class was ~90. Late-war group on both was US aircraft, so no worries about different types.

The largest air group I can find for an Illustrious-class was 42 fighters and 15 torpedo bombers, and that was for a special operation in 1944. The standard at that time appears to have been 28 fighters and 21 torpedo bombers. By comparison, the USS Enterprise in 1943 was carrying 36 fighters, 36 dive bombers, and 15 torpedo bombers - 77% more than an Illustrious standard group, 53% more than an overloaded Illustrious.

That is a lot of planes to give up. The Yorktown group looks like what I would imagine from a Lexington (though I suppose they were conversions) or an Essex. Overloading with aircraft probably complicated operations, and you'd have to compare with a similarly expanded air group on the Yorktown to be fair.

During our RTW2 discussions I was very much advocating for armoured carriers (with a substantial TDS) to protect our battleships from land based attack aircraft, and I still think that an armoured carrier primarily operating fighters would be useful in such circumstances. If you are operating on the far side of the Pacific Ocean, well beyond the range of your own patrol bombers, having an extra three attack squadrons (while not sacrificing fighters) looks very attractive. Midway would have worked out quite differently if the US carriers had no dive bombers - even though there they did have land based aircraft to support them.

I don't think any cruiser can survive being bracketed by a salvo of W23's, which is what happens about two minutes after it pops up over the horizon.

On second thought, maybe save a turret's worth of nukes and fire it a few seconds later, set to detonate in echelon along the threat axis, to mess up the guidance (if not the airframe) on any missiles that the cruiser might have managed to launch.

How likely are missiles to be launched, survive the trip and then, confused and unguided, to get within kill radius?

Or skip the nuclear artillery (although why would you) since the Soviets started to actually have missile cruisers in the mid-60s, so let AA escorts do their job and rely on an Iowa probably not needing nukes to take out a cruiser with the first salvo.

There are several problems with that approach:

First, the Mk 23 was not intended to be used that way. They had a single-digit number of shells onboard, which sort of rules out the AA barrage approach.

Second, the Mk 23 was a gun-type device, and very prolific with the enriched Uranium. The warhead on a missile was a lot cheaper.

Third, the missile cruiser is a lot more versatile. It's capable of contributing to air defense as well as to winning nuclear surface gunfights, and air defense is a lot more important most of the time. Also, the cruiser is much cheaper to operate.

All told, not a good case for the battleship.

Also, the 3T SAMs are faster than a 16" shell, so if both sides shoot simultaneously, the battleship will be destroyed before the guidance beam from the CG is disrupted.

In reality, human-factors and mechanical (e.g turret rotation) delays in initiating the engagement will dominate, so whoever shoots first wins. If one side brings a 45,000 ton battleship and the other side brings a 15,000 ton missile cruiser, and the only thing that matters is crew reaction time, one of these sides has chosen poorly.

Using 9 shells to take out an enemy missile cruiser loaded with nukes, sounds like a good deal.

Although a full salvo sounds like overkill. It might be enough to send 2 shells at the cruiser and a third set to go off about 10km from the battleship as barrage against the incoming strike.

But the shells would be some other type, since the Mk23 was retired in 62, when the Soviets had just launched their first missile cruiser. The Mk23 did prove that it was possible to shoot nuclear shells from 16in guns, so ordnance would have been (relatively) plentiful.

The ability to win nuclear gunfights is precisely what is being questioned. I'm not arguing that battleships can replace cruisers or escorts, only that those can't defeat battleships in stand-up fights either.

Wiki says that, of the three, only Talos had enough range to compete with battleship guns, and lists its max speed as Mach 2.5. I haven't found data on its acceleration and course, so I'll assume its time to target is maybe around 50-60s. Should be enough to put a fireball in its path. Could a Talos fly and home in through that?

Of course, in reality, both have onboard airborne ISR, and there would probably be other friendly airborne ISR around as well, so both know what's coming. Don't see why the BB couldn't just fire blind and bracket the CG's position with nukes just as its radar appears above the horizon.

I think you're coming at this the wrong way. Every country is going to build a fleet based on how it expects to fight and how the enemy expects to fight. And for the USN after WWII, that was primarily with carriers. So that means your primary method of killing ships is with airplanes, probably dropping nuclear weapons. Now, we know this doesn't always work, and there's a chance of an enemy ship getting in close to your carriers, which is very bad. We have two alternative contingency plans for dealing with this:

Keeping battleships in commission and buying a bunch of nuclear shells for them.

Using the nuclear SAMs already fitted to the guided-missile cruisers we were planning to buy anyway.

Option 2 is so vastly cheaper that nobody is really going to look at Option 1. Doesn't matter if Option 1 might be slightly better in a surface nuclear gunfight. If we're really concerned about surface duels between our ships and theirs, we'll build a nuclear-tipped ASM and slap it on our cruisers. The procurement cost of that is probably no more than the cost of buying the nuclear shells for the battleships, and the operating cost is vastly less.

Anyone who isn't expecting to use carrier aircraft is just going to take the nuclear ASM option, which is what the Soviets actually did. Nowhere in here does the battleship come out the winner.

If you have airborne ISR, then just hang the nukes on the aircraft.

SAMs in anti-surface mode can have more range than in AA mode. AIUI, doctrine was to fly the (beam-riding) SAM to a point in space, then turn off the guidance beam and let it fly ballistic to its target. That's going to buy you a bunch more range than a beam-rider would naturally have.

@Alexander -

"That is a lot of planes to give up. The Yorktown group looks like what I would imagine from a Lexington (though I suppose they were conversions) or an Essex." Yeah, the Yorktowns were pretty efficient little bird farms; while the Lexingtons were probably the best carrier conversions in any navy, they were never considered to be particularly efficient. More like, Big enough to be useful despite the inefficiency. The Essex class could carry still more, "up to 110" (but most commonly somewhere in the range of 90-105 AFAICT).

One thing I must concede, with respect to the RN's situation in the mid to late 30s: building CVs with the capacity to operate 80-90 aircraft is less useful if you can't obtain 80-90 aircraft to operate from them. And at the time the Illustrious class were being designed and built (indeed, until mid-war when Lend-Lease really got going), the FAA could not depend on getting enough aircraft to fill the carrier decks they did have, let alone any hypothetical "Pacific-style" carriers. (And that's without getting into the qualitative problems with basically all British-built carrier aircraft in WW2, which the RN could not have entirely foreseen.)

Yes. What I'm trying to say is that, after WW2, battleships would have gone away regardless of nukes. Not because they were made obsolete by nukes, which I don't think they were, and we can keep debating this if you like. But because, nukes or not, they were no longer necessary in the post-war context of complete US naval dominance.

I don't think this is true. First, nukes really changed the game for everyone. This is obvious if you dig into strategic thinking in the late 40s. Nobody was quite sure what the new rules were, and so lots of things were up in the air. You could make the argument that if not for nuclear-tipped SAMs, then the job battleships did would have been taken over by heavy ASMs in the late 50s/early 60s. But the basic point is that if the existing way of doing a job (in this case, using a battleship to guard against surface attack on your carriers) is much more expensive than a newer method (ASMs or nuclear SAMs) then it's effectively obsolete.

Re: original post topic, I'd think it's also relevant that your adversaries can react to your choices. All of the analysis in the post concerns battleships built to fight battleships, but if you stop building battleships, your carriers might end up fighting battleships* built to fight carriers. Not sure how that design would shake out, but I bet that making sure your carriers could outrun it would cost you more aviation capacity than just building some battleships.

I think the result of that process looks a lot like the Alaska class. High speed and guns capable of killing any normal cruiser. (There would be some differences, but that's a topic for a couple weeks from now.)

In regard to @Philistines point above. "One thing I must concede, with respect to the RN’s situation in the mid to late 30s: building CVs with the capacity to operate 80-90 aircraft is less useful if you can’t obtain 80-90 aircraft to operate from them."

It would have been quite interesting to see how the RN did in the Pacific in 1945 with a set of Ark Royal type carriers instead of Illustrious type. IIRC the armoured carriers were specifically designed with the expectation of conflict in confined waters like the Mediterranean as opposed to the design of Ark Royal which was envisaged as being used in the Pacific.

This is an interesting article about the survivability of a battleship against air power in WW2.

I would note several things.

The withdrawal of battleships as usable warships after ww2 was not because of the survivability but because of power projection. Carrier can project power several hundreds miles, battleships only to the range of her guns.

Carrier night operations It was a thing before WW2. The RN practice this before the war and was quite skilled for the time and with radar it was even easier. In the case of the Japanese raid on the Indian Ocean, admiral Somverville planned to attack the Japanese carrier fleet during the night as he knows that the Japanese has overwhelming strength. It does not happen as the Japanese were delayed and both carrier forces missed each other.

Sinking of PoW The TDS was not bad, the PoW receive a golden hit. No battleship could be made immune, especially not the ones designed with treaty limitations. Another important thing was that radar does not work in huminidity and there was no time to remedy that so her AA was quite ineffective. And there were quite a golden hits during a war vs. battleships. (HMS Hood, Bismarck, Scharnhorst, Roma and one of US battleship, do not remember which one get that torpedo hit which luckily did not get to the magazine).

In support of this, the USN 1944 instructions still seem to consider battleship-vs-battleship action (in lines) to be the normal form of a major battle, even between forces with carriers.

Though they also seem to expect it to be a daytime action, that might be ended by nightfall and where smoke screens are useful but to be used with care because they block both ways, despite frequently mentioning radar.

They vaguely feel older than they are, more like 1934 (which they say was the previous version) than 1944, but I'm not claiming that that feeling is meaningful.

...or like 1940, when such a battle (both sides making air attacks, but with little enough effect that it still progressed to a battleship-vs-battleship action) actually took place.

Though yes, also sort of like Leyte Gulf, so it was at least still reasonable to plan for the possibility of surface combat in 1944.

Not by a carrier's escort, but all 4 battleships sunk (plus 1 disabled) by surface ships after 1941 were trying to attack something beyond those ships (a land airbase, a convoy and a landing force. All were at night, and at least sometimes this was explicitly to avoid air attack.

To quote Louis Denfeld, “Fleets never in history met opposing fleets for any other purpose than to gain control of the sea—not as an end in itself, but so that national power could be exerted against the enemy.” It's not really surprising that those took place with other objectives in mind. Given how naval power worked even in WWI, it generally wasn't the case that one side was steaming around just waiting for the other to come out.

I was meaning that as more (a) battleships attacking at night to avoid aircraft was a real thing and (b) the defending ships were able to notice and stop them in time, i.e. before they could destroy the thing being protected, and not just provide after-the-fact retaliation. Though yes, I didn't actually say (b) and probably should have, sorry.

And hence, that while this never happened to a carrier specifically (the two carriers that were sunk by battleships were both by day and with only light escorts), it's reasonable to guess that the results would have been similar.

Though for (b), I don't actually know how often the opposite happened, i.e. how often a battleship destroyed something with nominally-strong defences because they didn't notice it in time.

Also, all the above were protecting fixed or slow-moving targets, while fleet carriers were usually faster than battleships. Hence, if they notice one before it gets into range but don't have a strong escort, they can simply run away (until dawn, then bomb it).

You're absolutely right about (a), and this was a major factor in the plans at least at Guadalcanal and Leyte Gulf. I think it was less so at North Cape, but I am less familiar with that action.

Re (b), I can't think of any cases that match the counterexample, but I might have to check my notes/book draft.

I do think "carriers can just run away" is probably overstated. For one thing, there might be land in the way. For another, if you're running, you can't count on doing air ops because you don't know which way the wind is blowing.

But we can probably salvage all of this by remembering that cruisers existed, and were generally more available and faster than battleships. So the carrier does have to worry about a serious surface threat, which I framed as "battleship" because that's my thing, and what the public generally talks about. And I think cruisers did surface raids and bombardments fairly frequently, although I can't think of too many examples offhand right now.

Agreed that smaller surface ships are also a threat to carriers, and possibly more of one because of their numbers and speed. (Though they never actually sank any carriers that weren't already disabled.)

As somewhat more evidence that surface ships usually couldn't win by surprise, this doesn't list any either - the one successful surface raid on an escorted convoy (out of 5 attempts they list) defeated the (much weaker) escort in a straight-up fight.

Cape Matapan and 1st Guadalcanal did both start at ~3km range at night, but their results don't obviously favour the side with surprise.

I jokingly think of the CVE naming theme as "being run down can happen to Bays (slow CVEs) or in bays (full CVs being cornered)", but have no evidence of that being intended.

This may be sounding like more of a disagreement than it is - I'm not claiming that running away is a perfect solution. Given that everywhere that built carriers 1936-45 also built new battleships and assigned them together, the battleship as escort was clearly at least widely believed to be useful.

Clarification: by "usually couldn't win by surprise", I mean we don't see "escorts don't notice anything until the enemy fires from relatively close range, carrier (or whatever) sunk by the first salvo before they can do anything" (at least by gunfire). I'm not claiming that's impossible, only that it seems to be rare.

Sort of correction: 1st Guadalcanal favours the side with surprise more than I thought - it's not only the only time lighter ship gunfire cripples a battleship, they do it without a numbers advantage - though it's more "chaos" than "surprise used well".

How sure are we that it's not just that these battleships, by being the ones that got subjected to this attack, are the ones for which we found out their flaws? I think that one needs to chronicle at least some of the battleships that survived air attack to substantiate a claim of this kind; one doesn't prove anything by 'explaining away' the ones that didn't.

This argument seems rather less convincing once one remembers that Britain running out of money was how we ultimately lost the Empire :'(

We're fairly confident. The British handling of power systems was worse than the Americans, and they had quite a few updates there for Vanguard. (Note that this got tested by SoDak at Guadalcanal, for instance.) Ditto the protective system, although that was mostly that money for large-scale trials didn't show up until after the ships were already being built. The South Dakotas and Iowas also had flaws there, although I believe less serious. Oh, and the 5.25" guns. The 5"/38 was pretty thoroughly tested.

Reviving an old thread, but another contributor to the demise of the battleship was the guided torpedo and SSN. You could attack carriers with those, but they can also keep up with a carrier and sink a battleship. If an enemy surface warship, even a BB, did get within gunnery or LOS-missile range of your carrier, the sub could send it to the bottom pretty quickly, guided torpedoes being much more reliable for this than straight-runners were, and attempting to "delouse" the carrier first wouldn't exactly be easy.

I'm not sure that's actually true. First, most early SSNs really weren't fast enough. Before the Skipjacks (1959), all of the American SSNs were 18-23 kts, which was a lot faster than previous subs could sustain, but definitely isn't fast enough to keep up with the carriers. Afterwards, the Permits (28 kts) and Sturgeons (25 kts) were also slower than you would really want. The LAs were the first designed with carrier cooperation in mind, and as such were capable of 30+ kts. Second, just keeping up with the carrier isn't enough. Coordination between surface ships and SSNs is still notoriously hard, so sending "hey, we just had a battleship show up over the horizon" isn't going to work. You could do it today with long-range sonar, engaging way before there was a threat but towed arrays didn't show up in service until about 1966, and before that, I'd be really worried about the sub being out of position. And the problem with torpedoes is that they're really slow compared to other weapons, so if you are out of position, then it takes way longer than you'd really like to deal with the problem.