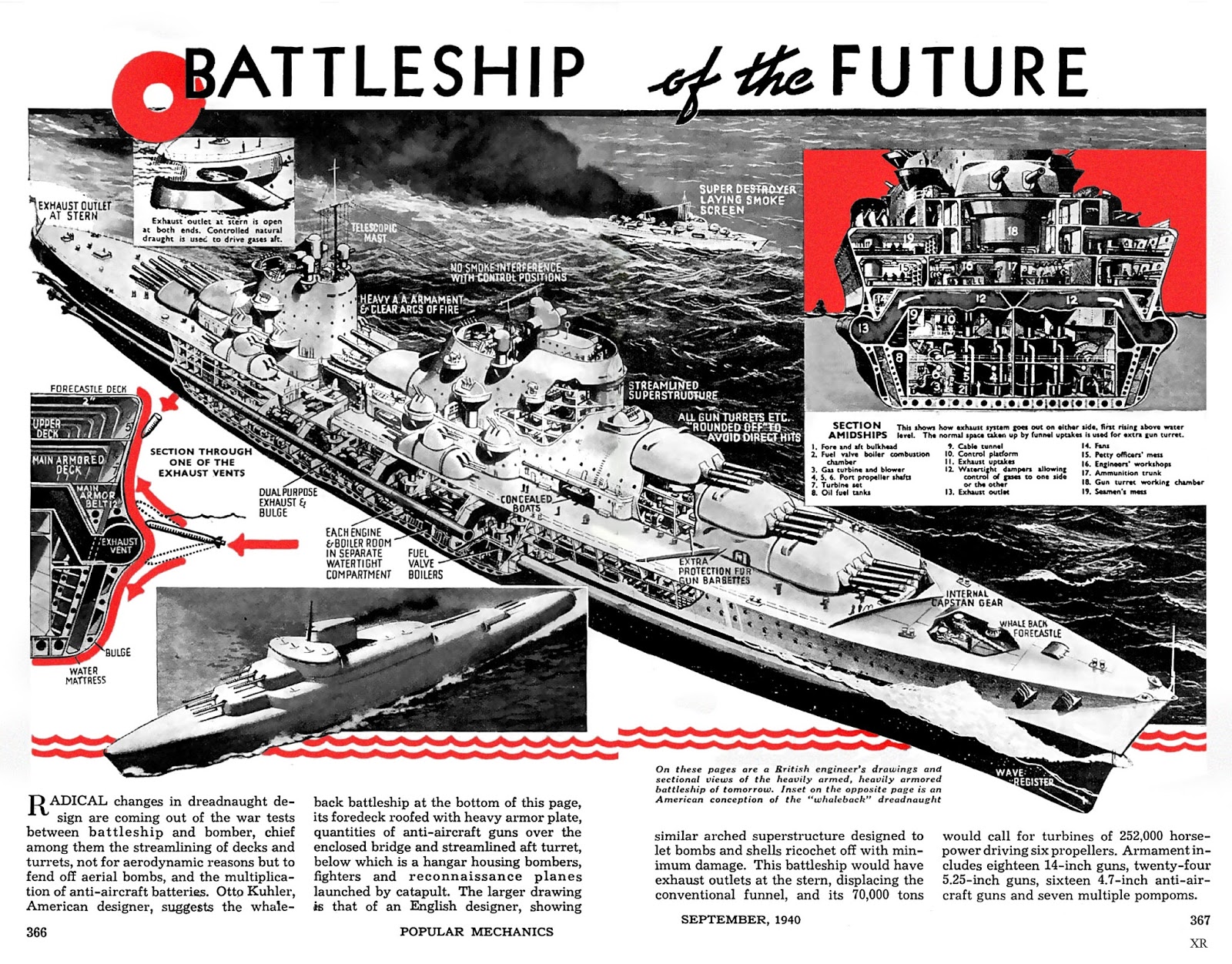

I recently ran across the following spread from a 1940 edition of Popular Mechanics. It's an interesting study in the way that outsiders get warship design very, very wrong.

I can sort of see where the designer of the main ship was coming from. He was trying to solve a few real problems, but did so in bizarre ways. Smoke interference was a fairly big issue for most warships, and finding another way to dispose of it would be nice, and would simplify topside arrangement, possibly leaving space for more guns. But his solution was the sort of thing that only a lunatic would come up with. Similar exhaust ducting had been tried on HMS Argus, an early carrier, with poor results. Heat was a major problem, and Argus was slow and low-powered compared to this ship. I suspect that backpressure would have given issues, too. Worse, the duct literally could not have been placed for greater vulnerability to underwater damage. Whoever drew the picture of it deflecting torpedoes had no idea how torpedoes worked. It would have been utterly destroyed by the first hit, and at very best, that would merely have forced half the boilers to be shut down. More likely, it would have provided a ready flooding path deep into the ship. I honestly cannot fathom how anyone believed this would be a good solution.

The armament is almost as weird. Double-superfiring was never tried on battleships for reasons of topweight,1 and a twin-over-triple-over-quad arrangement is downright bizarre. This triples the design effort necessary for the turrets over the use of a single type of turret, not a small consideration at the time. The arrangement was probably inspired by the twin-over-quad used forward on the King George V, but that particular configuration was adopted due to the need for a higher armored deck under treaty limits, and the ships were originally designed with three quads. The use of 14" guns was also bizarre, as even the British had adopted the 16" for their future battleships by 1940. A ship of this size, sensibly designed, would likely have a pair of 16" triples at each end, much as the US Montana class did.

The curved armor is also novel, and not in a good way. While sloped armor increases the incidence of a hit, and thus reduces the chances of penetration, curved armor is significantly more difficult to make than flat plates, and the increase in protection from AP bombs would be fairly minimal.

The secondary armament is also odd. Even the British, who had serious problems procuring medium-caliber guns,2 were unlikely to fit two different calibers to the same ship. Likewise, 7 pom-poms would have been seen as a laughably inadequate armament by the end of the war,3 although in fairness it was similar to 1940 fits on British battleships.

The whaleback design in the lower left is even weirder. Based on the picture, it looks like the turrets can't even train, which I suspect is a drawing error. The text describes it as being heavily armored against air attack, a possibility, and carrying an extensive air group, launched by catapult, which of course raises the question of how they're recovered. There's no deck to land them on, which means you're using seaplanes. Given the less-than-illustrious history of such aircraft in WWII, I don't think this was a good idea. The concept of a battleship-carrier hybrid tempted many nations before they recognized it was a bad idea,4 but most of those designs could at least recover their own aircraft. Without that capability, this design is simply silly.

Both of these designs are good examples of the sort of monstrosities that result when people with only a very limited understanding of the actual at-sea problems attempt to design battleships. There are some interesting ideas, but mostly in the same way that a car wreck is interesting. But it's a valuable lesson that the number of factors which go into a battleship, or any really complex technical system, is beyond the ability to those outside the field to comprehend.

1 It was done on a few AA cruisers, most notably the American Atlanta and British Dido classes, but these used small turrets relative to their size, minimizing the problem. ⇑

2 The US used the superb 5"/38 on everything. The British had at least half a dozen different guns in the same role, apparently because they didn't seem to think that a single weapon could meet the different requirements of various roles adequately. ⇑

3 Iowa carried 19 quad 40mm Bofors gun mounts of roughly similar size and role. ⇑

4 I'm aware of the conversion of Ise and Hyuga, but that was the result of a lack of proper carriers and time to build new ones. Nobody built them from scratch. ⇑

Comments

The cross-section shows the exhaust ducts going up over the waterline before dropping down into the weird excuse for a torpedo defense system, so you might not actually flood the engine rooms until the ship had taken on enough of a list that it was doomed anyway. Maybe no worse in flooding terms than the voids of a proper TDS.

But, you still lose half the boilers on the first hit for lack of an exhaust path. And with the actual outlet just above waterline level, there's no natural convection to speak of and the entire engineering plant is absolutely dependent on the blowers working. Which might be a reasonable sacrifice for a TDS that works. And if the Italians could believe Pugliese's system would work, I can see the same sort of false intuition at work here.

Unfortunately, actually testing torpedo defense systems is even more expensive than testing heavy guns vs. armor, so the pre-WWII designs are going to be mostly intuition-based.

That's not very far over the waterline. Any underwater damage, or even a reasonably rough sea, is going to start dumping water into your boilers, and that very rapidly leads to you imitating a WWI pre-dreadnought. Not to mention that one of the key lessons of all battleship design is to never fit something that's entirely reliant on your ship never being heavier and lower in the water than on the original design.

Disagree. The Pugliese system was based on model testing, and they got the tests wrong because scaling those is really, really hard. (Full discussion coming very soon.) This is going to fail in any test where even a reasonable effort at honesty was made.

But this isn't a pre-WWII design. If this drawing had come out of 1910 or even 1920, I'd be more merciful, but the article was published after Iowa was laid down.

Not a comment on the article, but on the website: the expansion of the image (click to expand, scroll to zoom, click-and-drag to navigate) is wonderful and I wish it was more common.

I was wondering what kind of 'battleship designer' ends up making sketches for Popular Mechanics. Otto Kuhler (behind the smaller-sketched ship) turns out to have been a real working designer--of locomotives and rail cars. Looking over his works, a big believer in sleekness.

Unfortunately the English designer of the larger-sketched ship is unnamed, so we can only guess.

Oh, he was a designer instead of an engineer. This makes a great deal of sense of that design, which I couldn't really figure out.

The continued use of mid-ship turrets (i.e. ones that can't fire straight ahead/behind because of the superstructure) after the first generation or two has always struck me as a poor use of space and tonnage. I realize that they persisted even until the Nelrod, but nonetheless they just seem like a poor idea.

@RedRover

I'd defend the NelRod turret as being rather different from traditional midships turrets. The biggest problem with those was that they were in the middle of the engineering spaces, which meant you had irregular powder temperature. Not a good thing. On NelRod, there was a deliberate decision to sacrifice astern firepower to save on the length of the armored box. It worked pretty well, actually. But battleships mostly fight on the broadside. Firing straight ahead/astern is a good way to get lots of deck damage.

Here, it's just bizarre. The ship would be vastly better if that turret went away and the two superfiring triples became quads.

Wait. Did he put the airplanes right under the midships turret? This can't possibly end well. Airplanes, particularly at that time, were rather fragile. South Dakota famously set her floatplane afire at Guadalcanal with the blast of her own guns, but it was at least at the other end of the quarterdeck. Here, it's right under the guns.

@bean

Clearly the idea is to use one of the guns as an improvised catapault! Just turn the main gun into the world's largest grenade launcher. : )

The telescoping mast was something that had occurred to me as useful-if-practical when reading about Jutland. At the end of the run to the south, Beatty confirmed scouting reports of the HSF being present by spotting the tops of the HSF's masts in time to turn around and get out of range. The main advantage of a tall mast is that it pushes the horizon back so you can spot enemy ships (for planning purposes and for fire control) at longer ranges, but it also extends the range at which your ships can be spotted by the tips of the masts rising above the horizon.

In a hypothetical situation where fleet A knows fleet B is coming from scouting reports and is trying to set an ambush, but fleet B doesn't know about fleet A, it seems like it would be useful for fleet A to be able to lower its masts so fleet B has to come closer before spotting the ambush. Of course, this is a corner-case to begin with, and an even rarer one in WW2 than WW1 because both sides will be using carrier-based planes to scout.

"SUPER DESTROYER LAYING SMOKE SCREEN" Uh, seriously? I mean, it's not something that makes the ship's design worse than it's already is, per se, it's just one more thing that the artist apparently didn't understand about naval warfare.

@Eric

The mast is actually another case that was probably overtaken by events. During WWI, you didn't normally put someone all the way at the top of the mast. They were mostly to support radio antennas and flags. During WWII, improved radio meant that this basically went away as a driver. Various other electronic bits were now at the highest point on the ship, but they were search systems, and not the sort of thing you want to haul down regularly.

@Aula

Actually, destroyers did lay smoke screens fairly often during WWII. Only the US and British ever had true blind-fire radar fire control, and even most of those systems weren't quite as good as their optical counterparts. A smokescreen could be useful if you needed to break off an action or hide valuable ships from the enemy. Taffy 3 deployed one at Samar. I'm not sure what a super-destroyer is, but I suspect a Gearing would count as one in 1940.

A "super-destroyer" is what you build when your budgeting folks just won't authorize any more CLs, I figure.

@bean

Sure, during WWII navies used smokescreens - of white smoke. Imagining in 1940 that future warships will lay black smoke as smokescreen seems utterly clueless to me. As a rare realistic detail in that picture, black smoke does rise up in direct sunlight, which is really not very desirable in a smokescreen.

I suspect that "super" got thrown in before "destroyer" merely because it sounded cool, without any thought given to what it might actually mean. That matches thematically the rest of the picture: lots of cool visual ideas which maker no sense once you start thinking about how they are supposed to work.

Actually, they used both. If it was a chemical generator, then it was white, but in a lot of cases, smokescreens were generated by burning extra fuel. Iowa has ports on her boilers, blanked off in the 80s, for doing just that. And the smoke is coming from amidships, which means it's stack smoke, not chemical smoke.

Absolutely agree. And I'll even agree that if the artist had known all of the various factors involved, he probably would have made the smoke white.

My interpretation may be wrong, but I think the idea was to have each of the boilers be separated in the exhaust front-to-back. So were you to take a hit to the exhaust, you'd only be looking at shutting down 1 or 2 sections of boilers on that side, not losing all of them on that side.

I don't think so. The diagram shows that the exhaust is all the way at the stern. It's also clear that the exhaust is going to both sides, which definitely means it's not being discharged along the sides. There'd be a tiny bit of sense in sending the smoke to the downwind side, which you'd fervently hope is also the disengaged one, but discharging on both sides guarantees that there's going to be lots of smoke right in your line of sight.

Second Battle of Sirte is another example of spectacularly successful tactical use of a smokescreen, even though it ultimately failed to save the convoy. C S Forester's lightly fictionalised account of it in The Ship isn't quite in the same league as The Good Shepherd, but still well worth a read.

I realized the other day: wouldn't Super-Destroyer be a pretty decent name for something with 6"/47 DP main guns? Same as how the 13.5" ships were called Super-dreadnoughts.

The most common use of the term super-destroyer is to describe the French contre-torpillers of the 1930s, starting with the Chacal class. These were very large for destroyers of the time, and extremely fast, although they didn't work all that well in practice. We call ships with 6"/47 DP guns light cruisers, because that's what they were. And they weren't small ones, either.