The attack on Pearl Harbor and the devastation of Battleship Row, are well-known. Less well-known is the later salvage of most of the battleships sunk that day, and their service around the globe, covering amphibious landings and providing fire support. However, five of them did get one moment of glory, fighting in the last battleship-on-battleship action in history.

Pennsylvania leading the US fleet near the Philippines

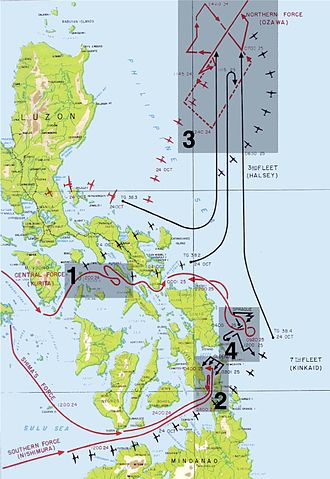

In October of 1944, the US launched its long-promised return to the Philippines, landing on the island of Leyte. This triggered the largest naval battle in history, the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The Japanese, who had planned for the ‘Decisive Battle’ between their battleships and those of the US for decades, designed their counterattack on the US landings around three main groups. Their carriers would come in from the north and draw off the US carriers covering the invasion, while two groups of battleships would sneak up on the invasion fleet from the east, passing through the Philippines and pincering the US transports from the north and south.

The northern group, denuded of planes after severe losses in June during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, managed to draw off Admiral Halsey. He’s often criticized for this, but his primary mission was actually to destroy the Japanese fleet, and the US didn’t realize how badly the carrier air groups had been hammered. The center group (with the faster battleships) had been detected, and appeared to have turned back after Musashi, Yamato’s sister ship, was sunk. They in fact resumed their course, and their encounter with escort carrier group Taffy 3 is the stuff of legend.

The action at Leyte Gulf, Surigao Strait is #2

The southern group had two older battleships, Fuso and Yamashiro, famous as the possessors of the ugliest superstructures ever fitted to dreadnoughts, the heavy cruiser Mogami and four destroyers. It was to pass through the Surigao Strait on its way into Leyte Gulf, and had managed to escape nearly unscathed by American air attack, if not unnoticed. They were followed by an independent cruiser group, two heavy and one light cruisers and 7 destroyers, far enough back to not participate in the main battle.

Photographic proof (Fuso)

Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf was the commander of the 7th Fleet’s heavy support forces. He had battleships West Virginia, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee, California and Pennsylvania. Of the survivors of Pearl Harbor, only Nevada was missing, on her way from the Atlantic. Oldendorf also had four heavy and four light cruisers,1 28 destroyers, and 39 torpedo boats. He placed the battleships across the northern end of the strait, with the cruisers in two groups slightly to the south. The PT boats and destroyers were distributed near the shore further south, to launch torpedo attacks as the Japanese came north.

Fuso or Yamashiro under air attack before the battle

And now, as John Schilling requested, I will tell the story of “Surigao Strait, where a Japanese task force encountered a fleet of invincible zombie battleships on a dark and stormy night”.2

The PT boats made the first contact at 22:36 on October 24th, 1944. They launched repeated attacks over the next few hours, but all failed to harm the Japanese. Then, at 0300 on the 25th, the destroyers began their attacks. The first two torpedoes hit Fuso after an 8-minute run, crippling her, and sinking her within the hour. Four more ships were hit by the next wave of torpedoes at 0320, Yamishiro3 and three of the destroyers. One merely lost her bow, while the other two went down immediately. Ten minutes later, Yamirshiro was hit again, but struggled back to 18 knots.

PT Boats preparing for the battle

At 0351, Oldendorf’s cruisers opened fire, followed by the battleships two minutes later. The Americans lay cleanly across the bows of the Japanese force, crossing their T perfectly. West Virginia, Tennessee and California had all been refitted with Mk 8 fire-control radar, while Maryland, Pennsylvania and Mississippi had the older Mk 3. West Virginia fired first, at 22,800 yards, and scored a hit on her first salvo. She was followed by Tennessee and California at 0355. Their fire was very effective, even though they were shooting over the cruisers part of the time. Initially, Yamishiro’s narrow radar signature made it difficult for them to see, but she began to turn to unmask Turret 34 at 0359, and this broadened her profile enough that Maryland was able to join the fight, aided by ranging on West Virginia’s shell splashes.

A map of the action

Yamashiro’s hull has been discovered, but she is upside down on the bottom, and the night action did not allow a careful examination of the hits, but she was badly handled by the American bombardment, and at 0405 she was hit by yet another torpedo. She finally managed to straddle the cruiser USS Denver a minute later, the closest she would get to damaging a major US warship, although a few destroyers suffered damage from her secondary guns. At 0409, Oldendorf was told that he might be hitting the American destroyer Albert W. Grant, and ordered a cease-fire. Mississippi had finally gotten on target, and fired the last salvo from the battleships, bringing to a close the era of the big-gun warship. Ironically, though she was not at Pearl Harbor, she later became the testbed for the RIM-2 Terrier SAM. Pennsylvania never fired during the battle.

West Virginia firing during the battle of Surigao Strait

Mogami had been disabled by cruiser gunfire, and she and Yamishiro turned south to try to rendezvous with the follow-on cruiser force. However, the battleship was caught by two more torpedoes, and began listing 45 degrees to port. By 0421, she was on the bottom, and only 10 of her 1,600 crewmen survived. The cruiser group following the battleships turned back after its flagship, Nachi, collided with Mogami in a rather bizarre case of bad shiphandling. The ships of that group, along with destroyer Shigure of the lead group, survived. Mogami, slowed by the collision, was sunk by airplanes the next morning.

PT Boats rescuing survivors

The victorious American battleships received a shock the next morning when they discovered the rest of the Japanese battlefleet bearing down on them from the north. Despite the depletion of the AP ammo, the battle line reassembled and headed north, only to discover that the Japanese had been turned back at great cost by one of the escort carrier groups. They would see action one last time during the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, in their traditional role of providing fire support. Several ships did prepare to meet Yamato if she managed to run the gauntlet of American aircraft to Okinawa, but it did not prove necessary.

Nor were the ships immune to damage (except at Suriago). Every one except the Pennsylvania took at least one Kamikaze hit, and Maryland was torpedoed off the Marianas in June of 1944. She made it back to Pearl under her own power, and was back in the battle line come August. Pennsylvania was torpedoed off Okinawa the next year, mangling three shafts. She was sent home, and never fully repaired due to her age and the late stage of the war.

Postwar, Nevada and Pennsylvania were too old (and Pennsylvania too damaged) to retain, and were used as a target vessels in the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll.5 Both were dangerously contaminated. Pennsylvania sunk off Kwajalein Atoll, and Nevada was sunk off Hawaii by gunfire and torpedoes from, among others, the USS Iowa.

California and Tennessee laid up in Philadelphia

The other ships were laid up in reserve, where they remained until 1959, when they were given up for scrapping. It’s sad that none of them were preserved, although I suspect that they were not well-maintained in reserve, and that made it uneconomical to turn them into museum ships. With their passing, an era in American naval history came to an end.

1 One of these cruisers, USS Phoenix, later became famous as the only ship ever sunk by a nuclear submarine in wartime. ⇑

2 To be pedantic, there were a few squalls, but it was actually a pretty dry night for the eastern Philippines. ⇑

3 Yamishiro was able to maintain speed, but had to flood the magazines for Turrets 5 and 6. ⇑

4 Turret 4 had been disabled by a hit early on, apparently a common problem with amidships turrets. ⇑

5 There were apparently efforts to save Pennsylvania (and the pre-Standard New York) as a museum. However, the Navy overruled them, and both ships were destroyed. ⇑

Recent Comments