I've recently been thinking deeply about the question of dual-purpose secondary batteries in the treaty era. Until recently, I've basically bought the line that DP is the obvious solution thanks to superior weight efficiency and the fact that you can build one gun which fills both roles. But further research has left me unsure of this, at least for most countries.

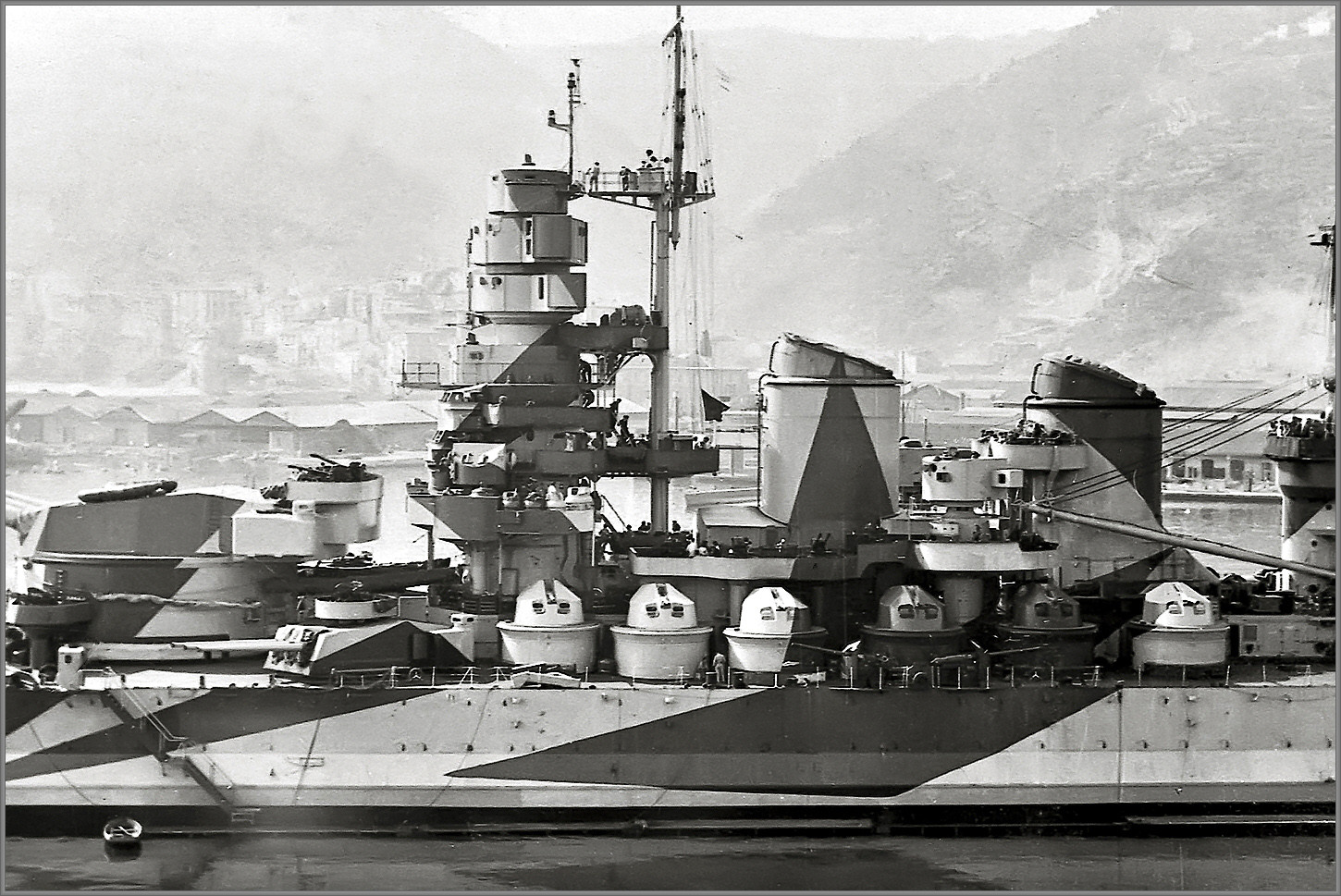

Vittorio Veneto displays portions of her secondary battery

The logic that Japan, Germany and Italy used in selecting their secondary batteries was all fairly similar. Basically, they thought that they needed a 6" weapon firing ~100 lb shells to be able to effectively counter destroyers. France also bought this logic on the Richelieu, although they chose to make those guns DP. They then discovered the problem with this, that a 6" shell is far too heavy to load rapidly, particularly at high angles, and were forced to join everyone else in fitting their ships with dedicated AA guns of around 4", which seems to have been the ideal AA caliber early in the war, with only the US not making use of it.

In many ways, the British ran into the same problem. While they didn't go all the way to 6", the 5.25" guns used on the King George Vs were selected because they would be more effective against destroyers than the 4.5" guns fitted to some of the Queen Elizabeths during their refits. But an 80 lb shell, cramped turrets and poor ergonomics meant that rate of fire was limited to 7-8 rpm. Some of this was probably because they thought that they could get away with it. The 4.5" gun that it replaced fired fixed (powder and shell together) ammunition that weighed about 85 lb, and that was capable of 12 rpm, at least in theory. But even that was clearly too heavy for really rapid loading, and it's not quite clear why the British didn't realize as the Americans did that the practical limit for a hand-loaded shell was at most 60 lb. Reports going back to the 4.7" AA guns on Nelson should have made it clear that 75 lb was too heavy.

5" guns aboard Iowa, 1943

So the only navy to really nail the DP gun was the USN, with the superb 5"/38 Mk 12, capable of throwing a 55 lb shell at 15-22 rpm, at least when in a mount with fuze-setters integrated into the hoists. This seems to have been the key to the gun's success in the AA role, as it gave a rate of fire higher than most of the dedicated AA guns fitted by other nations. While better fire control meant that rate of fire wasn't quite as important as it had been in the days of barrage fire, it still helped to get more chances at your target. And it had a big enough shell to be reasonably effective against destroyers, with any deficit in single-shot hitting power hopefully made up for by the fact that each 5" gun could generally match a 6" in terms of weight of steel per minute, and an attacker would be facing 60% more guns, which would hopefully offset the reduction in accuracy thanks to lower muzzle velocity.

But even the USN wasn't really happy with this, as evidenced by BuOrd's ongoing quest to build a higher-velocity gun firing a heavier shell to replace the 5"/38, entirely because of concerns about its effectiveness against surface ships. Bigger AA guns weren't seen as really necessary until 1941 or so, when faster and tougher aircraft prompted the development of the 6"/47 DP guns used on the Worcester class cruisers, and later overtaken by SAMs as the basis of long-range air defense.1

Midway shows her 5"/54 guns

Why did the USN get this right in a way that no other navy did? As best I can tell, this traces back to the decision to use the 5"/25 in the aftermath of WWI. When mounted aboard battleships and particularly the treaty cruisers (which had no other secondary battery) it began to be used as a dual-purpose gun. When the USN looked at resuming destroyer construction around 1930, the obvious answer was the 5"/25, although concerns about its accuracy during a surface engagement led to the decision to make the barrel longer and increase muzzle velocity. Most of the other features, such as the use of a cartridge case instead of bagged powder and power ramming instead of hand ramming, were inherited directly from that gun.

I am rather puzzled by the state of the evidence here. On one hand, every major navy was extremely concerned about the risk of surface attack, and it was the primary driver of caliber selection everywhere except the USN. On the other hand, the war itself saw very few cases where capital ships came under torpedo attack from destroyers, and even when they did, the destroyers were rarely particularly successful. On the other hand, capital ships did routinely face air attack, although as per my usual disclaimer, they were only rarely sunk by it. So in retrospect, the superiority of the AA-optimized armament is obvious. But it's always a good idea to avoid judging the actions of the past too harshly in light of evidence they didn't have.

But why were navies so concerned about the risk of surface attack? I suspect that a big development here might be radar. Without radar, there's a very real risk that you'll find enemy destroyers bearing down on you at point-blank range, and need to deal with them quickly. With it, your escorts can probably intercept them some way out. More broadly, surface torpedo attack generally failed to live up to its prewar promise, although the same is also true of the weapons that were to be used against attacking destroyers, most notably at Samar.

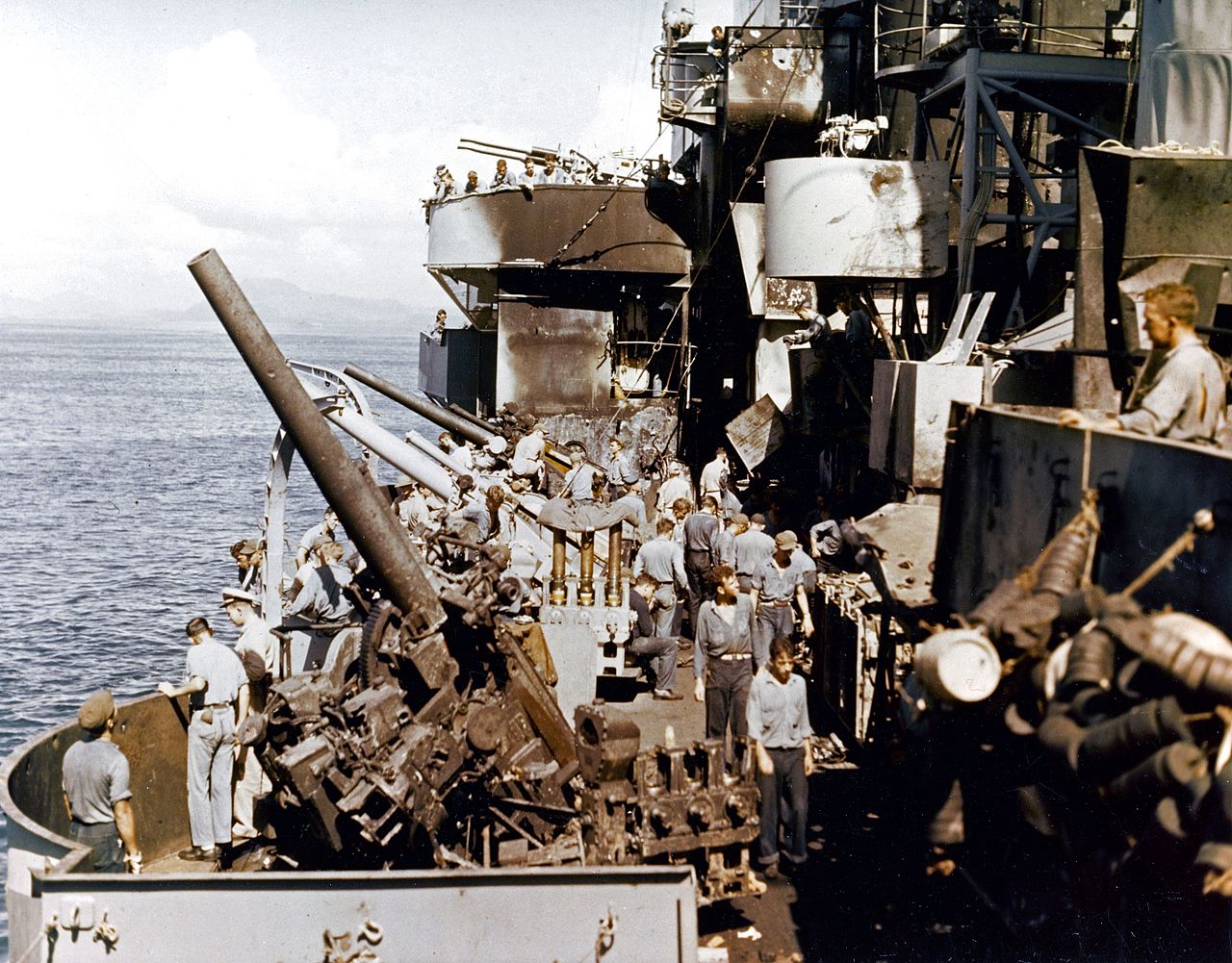

Kamikaze damage to the 5"/25 battery aboard Nashville

I'm not sure I have a clear conclusion to all of this. Obviously, if you have the 5"/38 with all of the trimmings, use that because it's just better. But a lot of the 5"/38's capability came from the mounting, most notably the integrated fuze-setter and better ergonomics, and Britain and France both demonstrated that it was easy to get the DP gun wrong. Both went with guns that fired far too slowly to be useful AA weapons, mostly due to heavy shells. The RN in particular should have been aware of this more than a decade before it was selected for the King George V. The 4.5" would have been a better choice, as it fired somewhat faster and more guns could be fitted, although it too was handicapped by a too-heavy fixed shell + powder combo. But this too could have been overcome, as the version of the 4.5" gun used on late-war destroyers fired separate-loading ammo and came close to the 5"/38 in rate of fire.

It's worth noting that the three nations which went for DP armament were also the three that took the treaties seriously. But I can also construct an argument for why the three nations that didn't go for DP guns might have prioritized split armaments without invoking the treaties, and I'm not sure that it's clear where the truth lies. Italy's battleships were the earliest of the treaty ships by a significant margin, and at that point, it probably wasn't as clear that aircraft would be a major threat as it was later. Also, operating in the narrow seas of the Med greatly increases the chance of running across enemy destroyers. Germany had always been weird in its choice of secondary armament, and many of its design choices in WWII look far more like clinging to things that had worked in WWI than thoughtful responses to modern circumstances. And Japan was operating entirely outside the treaty structure, and their focus on torpedo warfare might well have caused them to prioritize defense against destroyers. They did deploy a 5" gun, but it was only capable of 14 rpm burst, 8 sustained (at least in part due to the use of fixed-loading ammo), and planned to replace it with a 4" weapon on Shinano and later ships.

After going through all of that, I think my final takeaway is that yes, by WWII a dual-purpose secondary battery was generally a good idea, although quite hard to implement. More than that, the AA-focused DP battery of the USN was significantly better than the anti-destroyer-focused DP battery used by Britain and France for the war that actually happened, although it's still not quite clear how much of that was predictable ahead of time.

1 If you're wondering about the proliferation of 3"/50 AA guns in the postwar years, those were really a growth of the Bofors to deal with the same problem, largely enabled by proximity fuzing. ⇑

Comments

Dammit, bean, you stole all the points I was going to make on this subject. Especially the fact that there were a lot more capital ships sunk/damaged by a lack of AA firepower than a lack of anti-destroyer armament.

I think I have one left. The treaties, at a first pass, limited how much steel could be used in ships, not how many dollars could be used. I can't prove it, but I strongly suspect that part of the reason the US was able to build generally superior ships under the treaty system was because the US was willing and able to be relatively lavish with its dollars. Sometimes this was highly visible, like higher pressure steam plants saving a lot of plant weight and allowing more compact engine spaces that needed less armor length. But it also showed up in subtler ways, like the expense needed to get better turret ergonomics/automation that made things possible for the US that weren't options for other countries.

This, of course, should remind us all of my favorite truism of naval warfare: victory goes to the side that spends more money.

Destroyers being largely unarmoured, would the main disadvantage of an all 4" secondary battery be the reduced range? Or does the increased rate of fire and number of guns (for a given weight) not make up for the lighter shells?

Did any of these people document why they thought 6" guns were needed to stop destroyers? Because that's the part that doesn't really work for me. Taking Bismarck as the classic example of secondary batteries done wrong, if they'd just replaced the dual 15 cm SK C/28 mounts one for one with additional 10.5 cm SK C/33 mounts like they were already using for AA, the combined secondary battery would deliver ~90% of the weight of shell and about the same weight of HE per minute, with about the same accuracy and time of flight out to 17,700 meters, and without the problem of trying to coordinate multiple calibers. And saved 500 tons of topweight while almost doubling AA fire.

The 15 cm guns could ballistically reach 23,000 meters, but did anybody realistically expect they would be hitting destroyers at that range? And you don't need the heavier gun's armor penetration against tin cans.

6" secondaries make sense if you're planning to use them against enemy battleships at close range, e.g. in a night action, or as a secondary anti-cruiser battery. But those are both dubious plans for a dreadnought. For anything a battleship actually needs to worry about, and can't better address with its main battery, something in the 4-5" range just seems like a better fit.

@cassander

It's pretty clear that the US was spending dollars a lot more freely than other nations. That may explain some of the advantages we had over the British in particular. Most notable is the widespread use of STS in structural applications, which was fantastically expensive. On the other hand, the 5"/38 dates back to the very early 30s, at which point I think US spending was a lot lower than it was later.

@Alexander

Even though destroyers are unarmored, they're still pretty big, which makes them at least moderately hard to disable. A bigger bang is, all else equal, significantly more likely to do so, and the consensus among all nations was that 4" in particular was too small to do so. Remember that shell weight (and thus, to a first approximation, on-target effect) nearly doubles when going from 4" to 5".

@John

The general consensus was that 4" was too light against destroyers as far back as 1910 or so, and those destroyers were considerably smaller and lighter than those of the late 30s. A general lesson of both world wars is that, barring catastrophic stupidity, warships are actually pretty durable, and I could easily see it being that the 4" usually doesn't get deep enough to do all that much damage. There has to be some point at which that is more or less the case, with the limit being spraying a destroyer with machine gun fire.

Definitely in agreement that 5" is a much better caliber than 6".

Wherever I've seen this topic discussed, the criterion for effectiveness was "it needs to mission-kill a DD in one hit".

I never understood why it has to be in one hit.

Obviously, you do need reasonable accuracy beyond torpedo range, so you can't just spray them with 20mm. Other than that, more shots seems better on all accounts - higher chance to do some damage sooner (even if non-critical, it adds up), mess with their aim, plus two half-weight blasts do strictly more damage than one combined, right?

Even fighting other BBs, if you're shooting HE, square-cube means lots of little explosions have a better chance to break something than a few big bangs.

I'm just not getting it.

I think the one-hit mission-kill the criteria in about 1910, when the British did the trials that led to the adoption of the 6" on the Iron Dukes. In that context, it makes slightly more sense, as you're dealing with shorter ranges and worse fire control than you were in the 30s.

More broadly, I'm always nervous about endorsing something too far out of the mainstream of historical naval thought, and an all-4" secondary battery definitely falls into that category. Hindsight is great for picking between options that were thought reasonable at the time. But when we start talking about one that wasn't on the menu, I have to wonder if we're missing something important. In this case, I definitely haven't seen the results of firing trials. The only person who liked 4" secondaries after 1910 was Jackie Fisher, and while I respect him immensely, that was definitely into the phase of his career where his ideas were getting weird.

(I could see the argument for all-4" if you're making a late shift and don't have a 5" available, but that's a different issue from it being a good idea directly.)

Completely agree with this mode of thought. I'm inclined to believe the reason for high-caliber secondaries was a combination of wishing for long range, difficulties with fire control for very-quick-firing weapons at long range, and uncertainty regarding future technological developments.

For instance, something that would reduce the effectiveness of lower-caliber weapons, or large planes at very high altitude requiring 6" AA to reasonably tackle, or..? So better have some 6" DP, even if they're sub-optimal.

After all, they were near the end of a century of naval technology revolutions. Who knew what the next 10 years would bring?

Is the key here that the US was the first to make power-aimed mounts as accurate, and as simple to use, as hand-aimed??? And possibly related, the first to make them properly remote controlled and not just follow-the-pointer?

(AA guns need to turn faster than surface-only guns, so need power aiming from a smaller size. The 5"/38 is also intentionally mounted off-balance, to keep the loading tray height within easy reach at a wider range of elevations, and the British 5.25" looks like it also is.)

The 5"/38 offers basically the same user interface as a hand-aimed mount, i.e. position of handwheels sets position of gun, but this wasn't always the case.

Early powered mounts required the layers to directly manipulate the hydraulic valves (open this one to go up, or that one for down, close them slowly to avoid water-hammer damage - example from 1894). This sounds awkward enough to be bad at fine control. (The analogy that comes to mind is trying to play a first-person-shooter game with only the keyboard.)

Continuous aim was generally adopted for ~6" (hand-aimed), but not 12" (power-aimed), mounts around 1903. It seems plausible (though I don't have direct evidence either way) that this was because of this difficult control, and not (solely) insufficient speed in max-degrees-per-second terms.

The British worked on improving this, and considered their 1912 13.5" capable of continuous aim. 13.5" Orion came second in short-range practice, where the 12" had been noticeably less accurate than the ~6". Its German contemporaries were said to be even better at fine control.

However, as late as 1945, the British were still recommending that (against surface targets) powered mounts should avoid continuous aim (295iii) and some hand/power mounts such as the 1931 6" should use the hand mode for fine control (156).

This 13.5" and 6", and the US type shown in 1921 and 1937 Naval Ordnance (possibly not their latest, given secrecy), had a single control per axis instead of 1894's two valves, but still one that set speed (centered = stop) rather than position.

Powered mechanisms where control position sets output position did exist in other applications, including for ship's rudders from 1866, but might not have been accurate enough to be useful for a gun mount??

Though if that is it, "turns too slowly" seems an odd thing for the British 5.25" to get wrong, if you do actually mean its maximum rotation speed and not "too inaccurate" or "too vulnerable to damage"?

Maybe the navies wanting 6" secondary guns were concerned about torpedo attack not just by destroyers but also cruisers? The Japanese were using light cruisers as destroyer leaders, and those were bigger with maybe enough armour to keep out 4". If you're German or Italian, the Brits have a fair number of light cruisers with torpedoes as well. (HMS Enterprise had 16!)

@AlexT

I'm pretty confident that AA didn't drive 6" DP batteries. Only the French went for 6" DP, and it was because they didn't think the 130 mm DP guns they'd used on Dunkerque would be powerful enough for surface fire.

@muddywaters

That's a good point, although according to my sources it seems to have largely been worked out before the era in question.

That was it, per some combination of In Defence of Naval Supremacy and Naval Firepower.

That's only "turns too slowly when it lacks power". It's reasonably fine if it has power.

@Hugh

The only power I can confidently check that on is France, because as mentioned they actually transitioned, and I recall my source on that being reasonably specific about why. There wasn't that kind of discussion about other powers. That definitely seems plausible for preferring 5" over 4", although I'm not sure it really gets you to 6".

Follow on question - did most gun designs / designers start with a semi-arbitrary diameter and then work the ballistics and mechanical design to fit, or did they start with a given ballistic goal (X joules at Y meters) and work backwards from there?

It seems like the profusion of even number calibers (40mm, 4", 5", 16", etc.) suggests that they chose a "clean" diameter to start with, but then you have 5.5", .223", 88mm, etc, and I imagine that some of the clean diameters are actually approximations.

The traditional British series (47mm, 57mm, 3", 4", 4.7", 6", 7.5", 9.2", 12") was based on doubling the shell weight (i.e. *2^(1/3) in caliber) each step, but it's not exactly that. And as seen here, they did sometimes choose sizes not in that series.

In the time period discussed here, the treaty limits are a possible reason to pick 5" so it can also be your destroyers' main gun.

@redRover

They started from a size and worked from there. As muddywaters points out, the British sized their guns for a 2:1 shell weight ratio. I don't think most other navies were as systematic, but it's pretty easy to give a broad description of each type of gun, and figure out what kind you need. Particularly when designers strongly prefer to build in traditional calibers, where they have experience.

When it got solved is one of the things I'm confused about, given that it looks solved in 1912 yet still present in 1945.

Better fire control makes it more important to have precise aiming (as that's only useful if you/it know where it should be aiming), but whether that pushes towards hand or power depends on which actually is more precise in the time and place being considered.

Is this because heavy AA without good fire control was sufficiently bad at physically damaging the enemy that it was mostly useful for scaring them off (or at least into staying high enough that they'd probably miss), so it made sense to optimize for "lots of bursts looks scary" even if fewer bigger ones would have more chance of a fragment actually hitting? Or am I missing something that made it relevant to actually hitting?

Is this because seeing each salvo land before firing the next was considered necessary early on, but not later, and limited the rate of fire to less than a 4" could do??

Also true of the 5"/38?? Choosing either of these over a 4" is a choice to trade more effectiveness when you have power for less when you don't. Whether that's a good trade depends on how damage-resistant your ship's power grid is, and on how much of your effectiveness already relies on things that require power (fire control, radar, etc).

I might have subconsciously taken "good power aiming is the key to DP" from your earlier writing, so if you no longer endorse that then feel free to ignore me as well.

@Hugh: Friedman says a desire for 2" of armor penetration was one of the reasons the US decided around 1905 to move from 3"/50 to 5"/50 secondaries. He also says destroyers with that thickness over the boilers did actually exist, which I haven't seen anywhere else but is feasible weight-wise if it's just on the front (~10 tons).

The 1940s had 3" AP shells, but as the price of an AP's extra penetration is less damage, they're plausibly not a good idea where using a bigger gun is practical.

Quick question: Understanding the normal anti-surface round for a 6" gun was around 100lbs and thus too heavy to achieve a high enough rate of fire for effective AA warfare, couldn't you just have made the AA round for the gun much lighter, Say 50 or 60lbs? Shouldn't that give you a much higher rate of fire then (assuming the turret configuration and shell handling equipment were designed to support it)? I'm sure there's an obvious answer why this wasn't done (probably having to do with ballistics or something?) but just curious because assuming the turret could be designed to train & elevate quick enough, this sounds like it would be a way to make a DP gun without having to compromise.

@chris, I wouldn't assume that making the turret train and elevate quick enough would come before the shell handling equipment. From www.navweaps.com a British 6" WW2 cruiser gun fires shells that weigh around 50kg and are less than a metre long. The elevation machinery has to lift guns that weighs around 7 tonnes, more than 100 times heavier and over 7 metres long. The training machinery has to rotate a turret weighing around 160 - 180 tonnes. Making big heavy metal things move quickly and accurately is very hard, so my guess would be that by the time you've scaled from 5" to 6", the shell handling equipment is not a problem.

The first thing that springs to mind is that you're going to screw up your ballistics. A 50 lb 6" shell is going to slow down twice as fast as a 100 lb 6" shell (and considerably faster than a 5" 50 lb shell) which isn't great for shooting at targets at long range. You could sabot a smaller-caliber shell to overcome this, but that wasn't really technology they had at the time, and even if they did, the sabot has to go somewhere, and I'm not positive in their ability to keep track of where they are landing during a fight.

Even if you did overcome that, there's also the issue that by going for 6", you're inherently sacrificing mounts relative to 5" for weight reasons. And making a 6" able to train and elevate for AA use is going to drive up weight considerably. Look at how the British did destroyer main battery mountings for a lot of the interwar period.

Interesting idea, though.

@Hugh Fisher: they couldn't just scale up the shell handling the 4"-5" were using because it wasn't all machinery - on guns up to ~6", shells were lifted by hand from the hoist (fixed vertical) to the loading tray (elevates with the gun). This was (and on land, still is) both why ~6" was a common caliber, as the largest size where hand loading was practical when you didn't need high angles or very fast rates of fire, and one reason why crews were required to be physically fit.

(You could instead scale down the mechanical loaders the 8" and larger were using, but that would probably have been slower than a normal 6", partly because they often required returning the gun to a fixed elevation. Carrying a large amount of ammunition fixed to the gun like a scaled-up small arms or 20mm Oerlikon magazine would probably have been an explosion hazard.)

Hence, yes, such a light 6" shell probably could be fired at a faster rate than a normal 6", but it would also be less lethal than a normal 6" (less weight = fewer and/or smaller fragments = less chance of a fragment hit). The reduced range due to drag (maybe the equivalent of a normal 3") probably isn't a big problem for AA use, but I don't know if there would also have been accuracy issues.

And yes, this is slightly too early for sabot shells. In the 1950s, the risk of the sabot hitting a friendly was explicitly given as a reason for not using those, though I don't know if it was high enough to be the main reason. And for AA use, you're still basically turning your 6" into one 5", when you could have had 1.5-2 real 5"s for the same weight.

As for training and elevation speeds, power-aimed but not-officially-DP 6"s, including those considered here, were ~5-10°/s, compared to the 5"/38's 15-30°/s.

That's enough to follow most contemporary air targets. The near-worst case of a 300-knot target crossing (90° target angle) at 2000yd (for the USN, about the typical range to switch from heavy to light AA, and not far above the 1500yd minimum accurate range of the 5"/38's primary fire control system) is ~5°/s. Head-on targets (i.e. attacking you) are much less.

However, it would slow down getting on target, by ~10sec for 90°. For a single formation detected well out, you can do that while you're waiting for them to get into range. However, for one detected already within gun range (common pre-radar) or several attacking near-simultaneously, that's time a faster-rotating mount would have been shooting. (Though possibly not very accurately, since the fire control system also took time to work.)

As discussed above, there's also the possibility that they might not be able to accurately track at those rotation speeds, and the risk of damage taking out the power. Small guns can use hand aiming for fine adjustments or as a backup, but large ones can't, and what counts as 'large' depends on the required rotation speed.

The maximum elevation of 40-55° is also likely to be a problem against dive bombers. Increasing that requires more space in the turret for the back of the gun to move into.

Great discussion, thanks for all the info guys! Just a tangential follow up question: @muddywaters mention of the range that AA fire is switched from the 5" DP guns to the lighter automatics got me wondering. Were the lighter guns (40mm & 20mm) manned while the 5" DPs were firing? I ask because I noticed many of these exposed lighter guns appear to be well within the concussion/lung damage/death zone from the over-pressure of the 5" DP's muzzle blasts through a large portion of the DPs firing arcs. Or did the DPs just have to stop firing when the end of their barrels got too close to a 40mm or 20mm?

Yes, the guns were manned. I don't ever recall running across a reference to that being an issue (as opposed to the main gun blast, which definitely was) and I suspect that they just kept the smaller guns far enough away that it wasn't a huge issue and lived with it. Looking at diagrams of the Iowa, there may have been some small arc restrictions, but there are 20 mm positioned directly in front of a 5" one deck down, and I'd guess those were OK, although probably unpleasant when the 5" was firing.