The Fall of France put British mastery of the seas in grave jeopardy. Already overstretched by the efforts required to contain Germany and Italy, the Royal Navy now faced the potential that the French fleet would be added to the ranks of its enemies, bringing immediate disaster. Admiral Darlan, the chief of the Marine Nationale, did his best to make it clear in the days before and after the armistice that he would never allow his ships to be taken by a foreign power, and he was able to evacuate the vast majority of them to the French colonies in Africa, where the Germans and Italians seemed content to let them sit out the war.

Charles de Gaulle attempts to persuade his fellow Frenchmen via the BBC

Winston Churchill, however, was unwilling to let the situation develop, probably because he thought a decisive action was needed to boost morale and signal that he was not deterred by the loss of the French. Instead of even considering waiting for the ships to be moved back to German-controlled ports, the biggest concern for the British, they immediately began to take steps to neutralize them.1 The first was to approach French units about carrying on the war as part of Charles de Gaulle's Free French, but the response was almost unanimous. These officers saw the government now settling in at Vichy as the legitimate government of France, and breaking to join De Gaulle would be mutiny. The main effect of these overtures was merely to antagonize Darlan and other French admirals. Churchill ordered more dramatic measures taken.

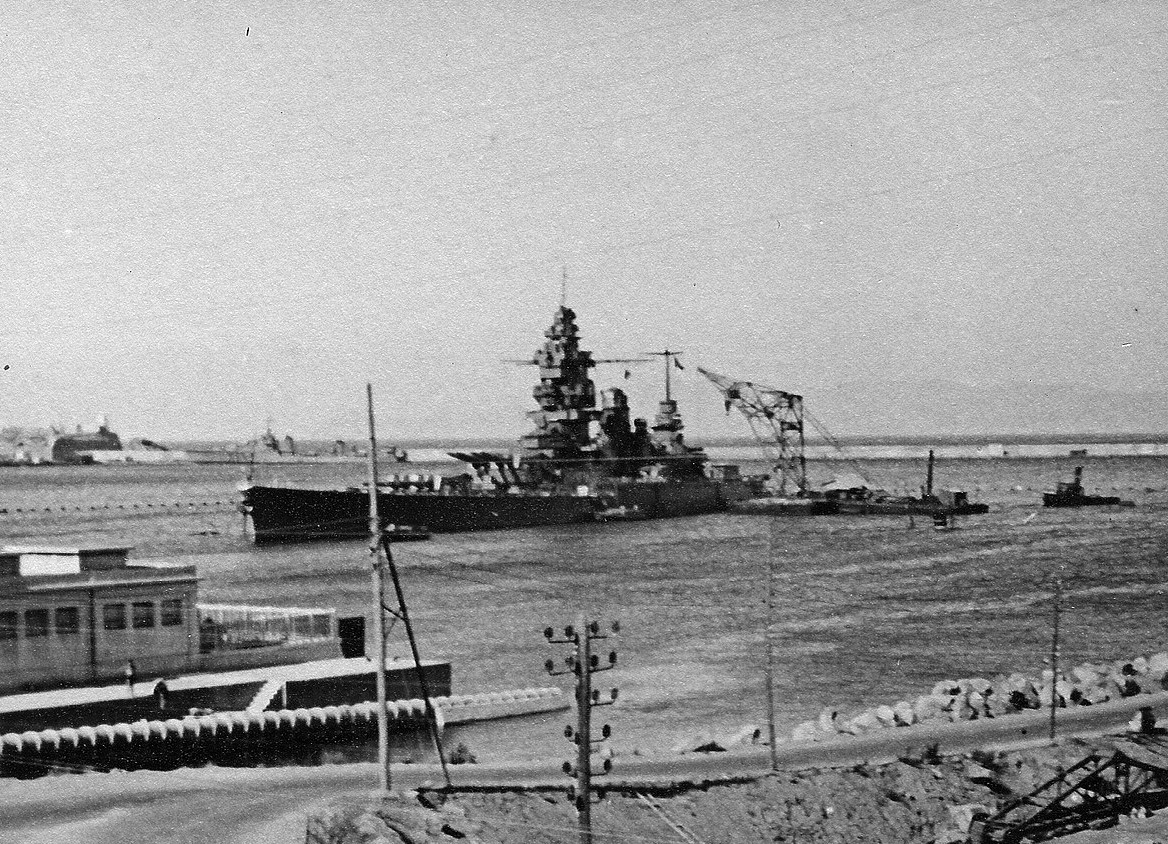

Battleship Paris after being taken over by the British

The first stage was simple enough. A number of French ships had ended up in British-controlled ports, either in England after evacuating the French Atlantic ports, or in Alexandria as part of the Allied effort to secure the Mediterranean. The French seem to have tacitly accepted that they would not be allowed to leave, and would spend the rest of the war interned, but Churchill went further, giving orders that boarding parties be prepared and officers sent to scout the ships under the guise of friendly visits. Many of the ships were anchored out in the roadstead, and they were brought in to tie up alongside under a variety of pretexts. British secrecy held, and none of the French officers suspected what would happen on the morning of June 3rd.

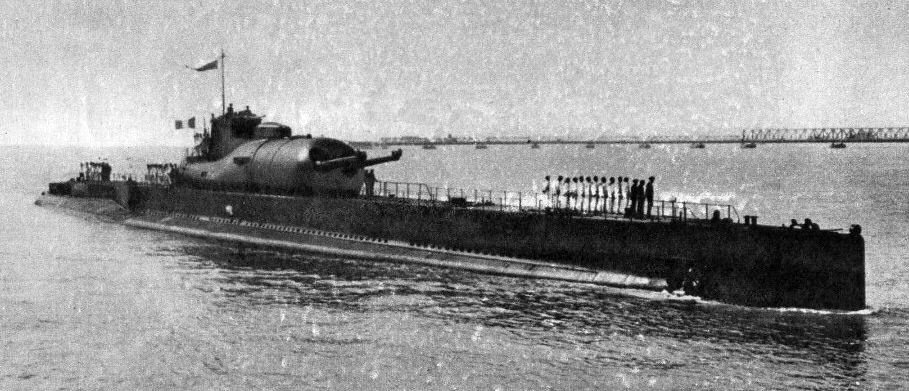

Submarine Surcouf in more peaceful times

Each vessel was protected by only a single sentry, who was approached by a British officer bearing an urgent message for the Captain. As he went to deliver it, the boarding party, concealed nearby, came aboard, securing the hatches and presenting the crew with an ultimatum. At Portsmouth, the seizures were carried out without bloodshed, but things went less smoothly at Plymouth. The officers of the destroyer Mistral attempted to scuttle her, and were only stopped when the British locked the crew in their quarters and refused to release them until the ship was handed over. Aboard submarine Surcouf, things went even less well, with the French opening fire on the boarders. Three of the British party were killed, along with one Frenchman. Despite these setbacks, the British managed to secure over 200 ships. Most were small, minesweepers and the like, but they included the obsolescent battleships Paris and Courbet, and a number of modern submarines and destroyers.

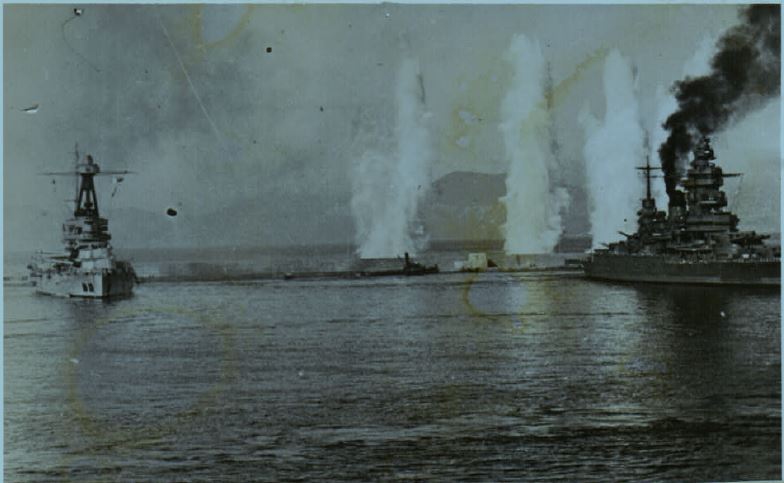

The French fleet in Mer-el-Kebir

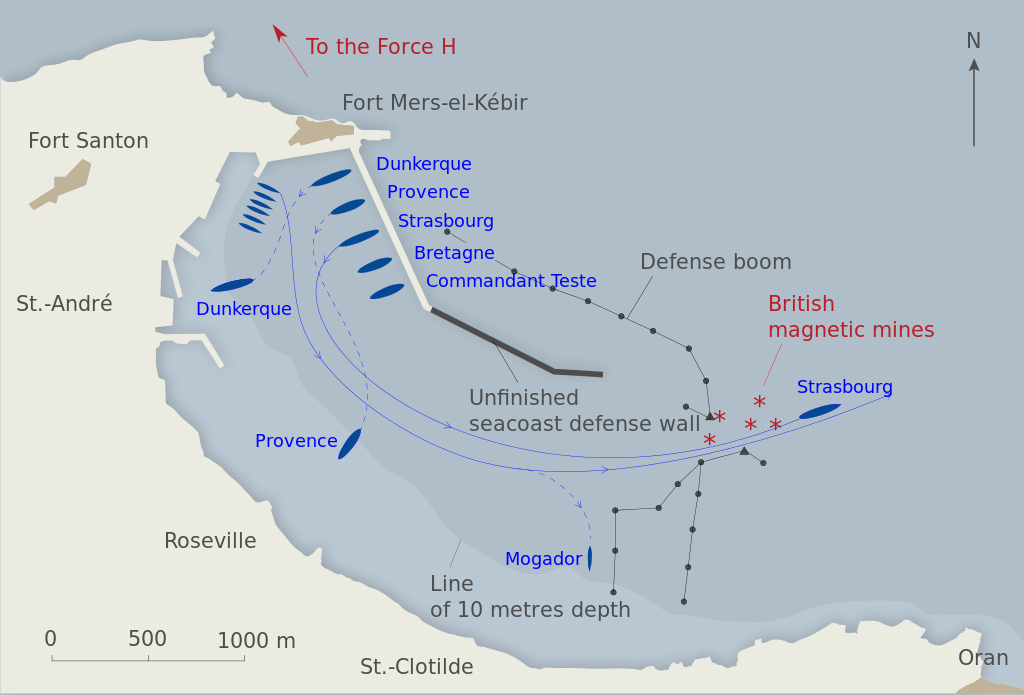

But that only took care of a small portion of the French fleet. The biggest remaining concentration was at Mers-el-Kebir, near Oran in Algeria, including the modern battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg and the older Bretagne and Provence. They had initially been stationed there to defend the western Mediterranean against Italy, but now proved a tempting target for Churchill. To deal with them, he dispatched Admiral James Somerville with Force H, out of Gibraltar. Somerville had battlecruiser Hood, battleships Valiant and Resolution and carrier Ark Royal under his command, and on the morning of July 3rd, his representative delivered an ultimatum to the French. Either they would rejoin the Allies, be interned in British hands, be disarmed in the French West Indies, or be turned over to the US for safekeeping. If one of these wasn't selected within 6 hours, Somerville would open fire. The French commander, Admiral Gensoul ordered his ships to raise steam and clear for action while he played for time. Somerville was stuck aboard his flagship, and Gensoul refused to negotiate directly with the British representative, sending his own subordinates to do the job. This prolonged negotiations, as British planes flew overhead and Gensoul tried to get in touch with Admiral Darlan. Darlan couldn't be reached, and ultimately, at 1755, the British opened fire. Gensoul ordered his ships to get underway.

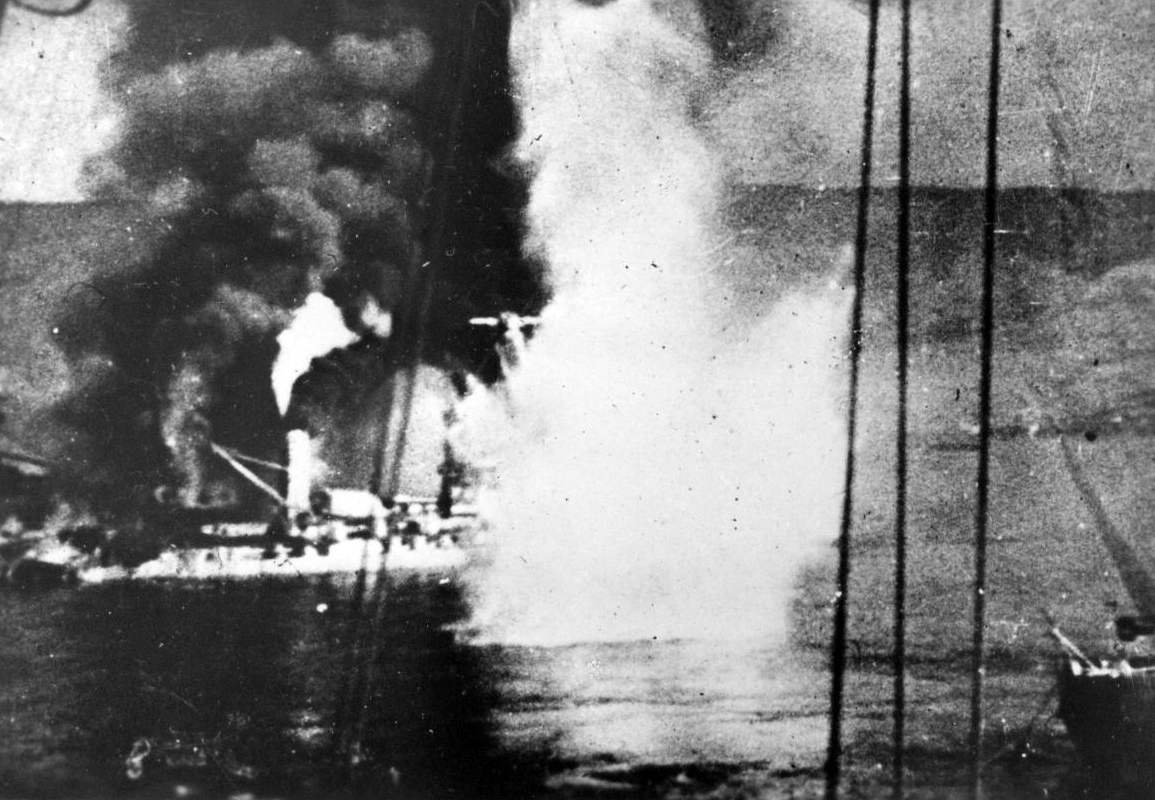

Bretagne burns after being hit

The British gunnery was excellent, as might be expected when shooting at stationary targets. Dunkerque, Bretagne and her sister Provence were each hit within the opening minutes. Only Strasbourg, the newest vessel present, managed to get underway, heading with the destroyers for the gap in the anti-submarine net, and threading her way through the forest of shell splashes that filled the harbor. Bretagne was hit early, with one shell triggering an internal explosion and another destroying the central engine room. All power was lost, and two more shells hit a few minutes later, one of which set off a massive internal explosion. She capsized ten minutes after the action started, taking 1,012 men down with her.

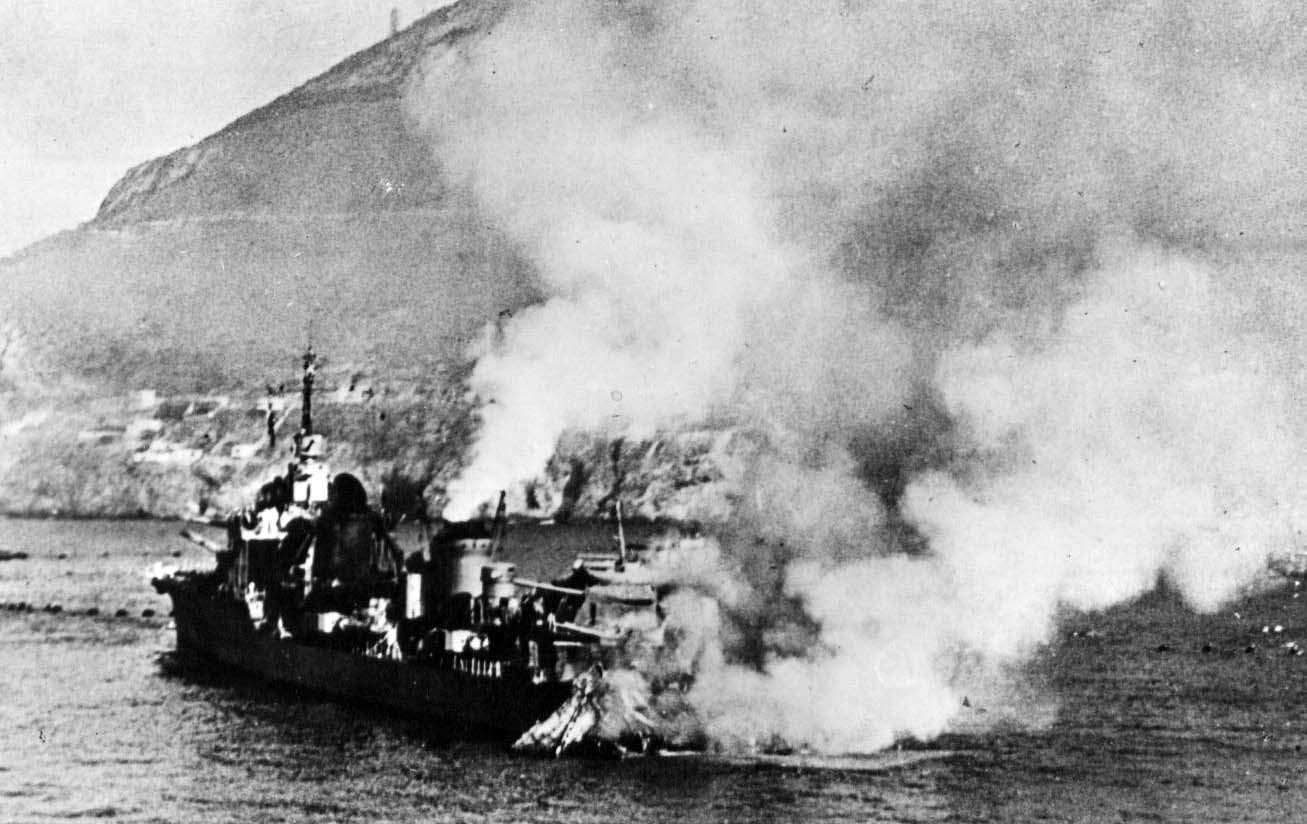

Destroyer Mogador aground

The other ships were somewhat more fortunate. Dunkerque was also hit by the opening salvoes, with one shell hitting Turret 2 and wiping out the gun crew on the right pair of guns.2 A second struck aft, cutting the control cables to the rudder. A few minutes later, two more shells struck, penetrating the belt, and detonating in the engineering spaces, quickly disabling the ship. One of the shells also started an ammunition fire. Dunkerque was out of the fight, and while she had technically gotten underway, she was beached fairly quickly to keep her from sinking. Provence was only hit once, but the resulting fire forced the aft two magazines to be flooded, and she was also grounded in the harbor. Destroyer Mogador was also hit, with a 15" shell setting off her depth charges and forcing her to be run aground to avoid sinking.

Strasbourg makes her break for freedom

Strasbourg made her escape, threading her way past the magnetic mines dropped by Swordfish from Ark Royal.3 and followed by three destroyers. Somerville initially refused to believe reports of the escaping ships, trusting in the mines, and Strasbourg managed to get away cleanly. When the British realized what was going on, they gave chase and attempted to slow the French battleship with air strikes from Ark Royal. The attacks were unsuccessful, and Somerville abandoned the chase. Strasbourg's arrival at Toulon the next day was greeted with jubilation, while the attack itself caused a great deal of bitterness on the part of the French. Astonishingly, they didn't respond to the literal act of war on the part of their former ally by throwing in completely with the Axis, the worst-case scenario for the British, instead choosing only to bomb Gibraltar and then sever diplomatic relations. The rupture between the two nations was only patched when the French government was replaced by DeGaulle at the end of the war, and the resulting bitterness took a long time to fade.

Dunkerque under repair at Mers-el-Kebir

Almost as soon as the fires were out, the French began work on refloating Dunkerque. Word reached the British, who decided to deal with the problem with an air raid. A dozen Swordfish appeared over Mers-el-Kebir, to find Dunkerque defenseless before them. They hadn't been detected on the way in, and to convince the British that the ship was derelict, the light AA guns were unmanned. As it was, the shallow water frustrated the attack, and none of the torpedoes hit the battleship. One did sink a patrol boat tied up alongside, and she sank before her depth charges could be secured. A few minutes after the British departed, 14 of them detonated, almost a ton and a half of explosives only a few meters from Dunkerque's side. The damage was extensive, and if the 330mm magazines hadn't been flooded when the Swordfish approached, Dunkerque would almost certainly have been destroyed. 210 officers and men were killed aboard between the two attacks, and repairs at Mers-el-Kebir took until February of 1942, when the ship transferred back to Toulon.

Shell splashes rise from the harbor

And for all its diplomatic consequences, the operation was also a tactical failure. Strasbourg was essentially undamaged, and she and a number of other ships relocated from the relative safety of North Africa to Toulon, where the Germans had a much better chance of seizing them, while the initial damage to Dunkerque was far from fatal, and even the later damage was not enough to put her entirely out of the war. To make matters worse, the provisions of the armistice requiring the French ships to be disarmed were suspended to allow the vessels to counter any further aggression by the British. Churchill, however, spun the operation as both a necessary response to the imminent surrender of the ships to Germany, which would prove false, and as a success, despite the damage it did to the British position in the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, many later historians have followed this line, or chosen to overlook the operation entirely.

The attack on Mers-el-Kebir also put the last major French force, at British-controlled Alexandria, in an extremely difficult situation. We'll take a look at its fate, and that of the other French ships not in Oran, next time.

1 I find British thought during this period hard to understand. Arthur Marder defends them by pointing out that German landings were expected to be imminent, and they wanted to wrap things up before that could happen. Even if we ignore the silliness of the German invasion on such short notice (a topic for another time) there's still the problems of finding crews and making the captured ships effective. The Kriegsmarine obviously had no experience operating French ships, and didn't have spare crews for a bunch of battleships sitting around. Even if they had, it still takes time to work ships up, and the earliest I'm aware of any battleship going into action was Prince of Wales at Denmark Strait, four months after commissioning and a month after she was finally declared complete. (Yes, I have those in the right order). Her performance in that action suffered noticeably due to the inexperience of her crew, who were still working bugs out of the machinery. There's no possible way any captured French ships could have been battle-ready until August, and most likely not until 1941, giving the British enough time to take action. There's also the minor matter that the plan actually adopted was a literal act of war against France, which could have pushed France into actually joining the Axis, which could have brought both surviving ships and their crews into the Axis navies. ⇑

2 The quad turrets on the French battleships were divided in half, with a central bulkhead to limit damage. ⇑

3 Interestingly, the French thought the ship's degaussing system would protect her, but it turned out to have been installed incorrectly. ⇑

Comments

Two minor points that probably merit additions:

You mention the British fleet being screeched thin by needs in Europe and the Mediterranean. The Far East also wants lot of ships making everything worse.

The unprovoked act of war against a neutral power, from what I remember, didn't play well in America, whom the British need to go cap in hand to.

Also, (tongue slightly in cheek), who overthrew the French government more times, de Gaul or Napoleon?

....In "The Fall Of The Third Republic", William Shirer gives a portrait of the French fleet and its commanders that is somewhat less than flattering.

On or about June 29th - Shirer is uncharacteristically vague here - US Ambassador William Bullitt sat down with Admiral Darlan to try and convince him to get the French fleet clear. Darlan, however, would have none of it. He told Bullitt that he had no trust in the British, and "under no circumstances would he send the Fleet to England, since he was certain the British would never return a single vessel of the Fleet to France, and that if Britain should win the war the treatment that would be accorded to France would be no more generous than the treatment accorded by Germany." He followed that up by telling Bullitt that he backed Petain, Weygand, and Laval to rid France of the Republic. (He then told Bullitt that German troops had just entered Spain at Franco's request on their way to Gibraltar.)

It gets much, much worse. By this time, the entire French high command was thoroughly unwilling to continue the fight, and were to a disturbing extent more interested in preserving their own reputations than anything else. By July 3, Darlan had told Admiral Gensoul "not to have any relations with the British", and Gensoul was more than happy to cooperate. Somerville had sent CAPT Holland (IIRC skipper of HMS HOOD) to bring the ultimatum to Gensoul, and Gensoul then sent a LT, which slowed things down further.

Finally, after getting a full briefing from Holland, Gensoul contacted Darlan....and told Darlan that the British had told him, "Sink your ships within six hours, or we shall use force to make you." It appears Gensoul NEVER told Darlan about the other options, not that it might have made much difference in the end.

Finally, at 1700 that day, the French actually appealed to the Germans for assistance. They in turn most graciously suspended the terms of the Armistice applying to the Fleet so that they could fight the British. (That order, BTW, came from der Fuhrer his own self.)

By July 3, the French had no desire to fight the Germans in any way, shape or form, and they would be damned if anyone else was going to make them. Their leadership had decided that the only way to survive was to obey the Germans to the letter, and by God they were going to do it.

@ike

I have to disagree on point 2. One of Churchill's reasons for the attack was to show the Americans he was still in the war, and it seems to have done that.

@Mike

This is diametrically opposed to what my main source (From Versailles to Mers-el-Kebir, fairly recent from USNI) says. The index doesn't mention Bullitt so I can't check that particular detail, but it makes a strong case that Darlan was extremely interested in keeping the French fleet independent. Out of British hands, yes, but also German. I attempted to compensate for any pro-French bias in that book by double-checking against Marder's From the Dardanelles to Oran, which didn't do a whole lot to convince me otherwise, and I'll generally take a book from the past 10 years over one from 1969, all else equal.

Actually, it's also worth pointing out more clearly the position that the French leadership saw themselves in, as opposed to the one we retroactively see them in today. Things in the UK were still pretty touch-and-go with respect to saying in the war (paging Halifax...) and the Franco-Prussian was either within living memory or recent history for the men running France. The idea of "OK, you beat us, now let's have an Armistice" wasn't foreign to them, and they were rightly concerned with getting the best terms they could for their country, and not making things worse postwar. Other countries had been able to rely on powerful allies (Britain and France) when the Germans invaded and could fight from exile with reasonable hope of victory. France wasn't in the same position when they were defeated.

The second option in the British ultimatum at Mers-el-Kebir was that the French ships should "[s]ail with reduced crews under our control to a British port". You've interpreted this to mean that they would be interned in British hands.

I had thought this option implied that the French ships would be recrewed - with either British or Free French sailors - and operated as part of the Allied fleet for the remainder of the war. This is supported by the next line of the ultimatum, which promises that Britain will pay compensation to France for any damage to the ships during the war, and the following line, which presents the possibility that the ships should not be used against the Germans as an alternative to the first two options.

Did you mean to exclude this option, or were you just simplifying for brevity? How practical would this option have been: to recrew warships without the benefit of institutional familiarity with them, or to operate them without compatible supply chains? (Did the British and the French use the same voltages, the same sized bolts, etc?)

There was also one more option in the ultimatum which you haven't mentioned: it suggests (possibly in case they didn't trust the US to remain neutral while the ships were interned there?) that the French ships could instead be scuttled. For interested readers, I highly recommend looking at the original text of the ultimatum.

Typo, I think: Bretagne, not Bretange.

Exactly this. Additionally, the fleet was something the Germans craved, but could not get if they invaded what was left of France. The best French move was to keep it that way, enforcing the status quo, and wait to see what happens next.

@DampOctopus

I think that line is somewhat ambiguous, and the version in the post is the one that I came away from my research with. I'm sure that if they'd have accepted, the ships would have eventually been turned over to DeGaulle, but a lot of it was going to depend on things like finding crews. As for damage, if they're in British ports, there's a decent chance they'll end up being bombed and such.

As for support, it's worth pointing out that Richelieu was operated by the Allies from 1943 on, so it can't be totally excluded, but I suspect that this wasn't possible until the US joined the war for industrial reasons.

@DampOctopus the following line, which presents the possibility that the ships should not be used against the Germans as an alternative to the first two options.

I assume this would mean that they would have ended up in the Pacific, probably moored at Singapore. Which would have ended with them in Japanese hands.

Or they'd be in Sydney I suppose.

@Doctorpat: The ultimatum says (paraphrasing): "If you don't want your ships used against the Germans, you could intern them in Martinique or the US.". There's no implication that they could have been used against Japan - which, remember, was at peace with the Allies at this point.

@bean: I agree that the line about damage is ambiguous, but the following one seems clear to me: it implies that, in either of the first two options, the French ships would be used against the Germans. For that matter, why would the British make the suggestion that the ships should sail to a British port if they weren't going to get any use out of them? If they were to be interned, I would have thought internment at a neutral port would be the preferred option for both France and Britain.

What did you come across in your research that convinced you otherwise?

Regarding the practicalities of Allied operation of French ships, it seems there were three French battleships (of WWI vintage) that ended up under Allied control through the middle period of the war: Courbet and Paris (seized in Operation Catapult) and Lorraine (crew defected to the Free French). They had generally undistinguished careers as barracks ships, anti-aircraft batteries, etc., though they did sail (or were towed) to provide naval support for Allied efforts in Western Europe later in the war. Lorraine seems to have been the most active of them - possibly because she was the only one with her original crew?

I'd say Bretagne, not Bretange...

Yes, it's Bretagne. Typo has been fixed.

@DampOctopus

I'd guess the "intern in Britain" line was deliberately non-specific. Obviously, there's no promise they won't be used against Germany, as there is with sailing to America, but there's also not a promise that they will. I'd guess it was intended to give Gensoul a middle ground, where the ships would be available for use (maybe turned over to de Gaulle), but not leave him deliberately saying "OK, let's go join the fight". A lot is going to depend on their ability to crew and support them.

To that end, it's worth looking at the ships the Allies did end up with. Lorraine was more modern than Paris or Courbet, and she wasn't turned over to the allies until 1943, when the US was in the war, and the Free French actually could recruit people (which they couldn't in 1940 for obvious reasons). But the two older battleships were demilitarized and never used as warships again. The British might have managed to scrape together crews for Dunkerque and Strasbourg, but I'd guess most of the rest would have spent quite a while just sitting there.

Unfortunately, the details that go into writing decisions like that tend to get purged when I'm done with the series.

The invasion panic makes a little more sense once you try to put yourself in the shoes of the British at the time, and limit to things that they knew, and thought they knew.

To external observers, in mid-1940 it looked very much like the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany were in a full alliance. There was a lot of trade going on between them, they invaded the states between each other without any complaints between them, even when some of those states had strong pre-existing ties to the other power. In Poland, the Soviets invaded the country together with the Nazis, and clearly stopped at a mutually agreed-upon line. So on this basis it looked like Britain was facing not just Germany and Italy, but also the Soviet Union, which meant they were now alone in a war against everything between Dover and China. It really did look rather dire on a map.

In mid-1940, the Nazi leadership appeared hypercompetent. They had done multiple things that competent observers would have claimed to be completely impossible. Even the invasion of Poland went way better than anyone thought it should go, the invasion of Norway and especially Case Yellow just looked like a total OCP. Other than Dunkirk (which mystified the British), it very much looked like everything the Nazis did always went exactly as they planned. In hindsight, we know that the Nazis were mostly winging it, but that's not at all what it looked like to outsiders when it was happening.

There were spies in Germany, in low-level positions who had started talking about the Army preparing for invasion. They couldn't say how it was supposed to happen, just that everyone knew that Britain would be next, that it would involve the Army (so it would be an invasion), and that people above them were acting like they knew what they were doing.

These three points, taken together, make a very strong case to believe that an invasion is imminent, even against all the other evidence that existed at the time.

Your enemy, who commands much greater resources than you, is capable of concentrating all of those against only you, and who until now has succeeded in all his plans, many of them which you thought to be completely unfeasible before they were put into action, is planning to invade you. Even if you have no idea of how they are supposed to do it, it makes some sense to prepare as if you thought they could do it.

Lastly, in mid-1940 no-one in Britain had any illusions about being able to effectively hinder the German advance if they succeeded in landing in force. Famously, after the loss of all the equipment of the BEF, they had less AT gun rounds than the Germans had tanks. So everything hinged on not letting the enemy across the channel, and to hell with anything in the way of that.

A reasonable point. I'm particularly convinced by Point 2, in that most of the world's expertise in amphibious operations is currently staring across the Pacific instead of the Atlantic, and we today have learned a lot from the later part of the war, which very clearly shows how impractical Sea Lion was. The only amphibious operation in Europe up to this point would have been Norway, which I know less about than I should, but which seems like it might have convinced people that they could do the same to Britain.

Tuna:

That's been Britain's position for a lot longer than just WWII.

Thinking it over more, the British at the time seem to have been afflicted by the same delusions about Nazi invincibility that you get in the worst of the Wehraboos, although with somewhat more reason.

It wasn't just the British - look at the invasion panic on the US West Coast after Pearl Harbor, which if anything was even LESS justified. At least the Germans thought about invading Britain at some point, and they had a plan (however implausible) to attempt it. The Japanese didn't even get that far.

"Astonishingly, they didn’t respond to the literal act of war on the part of their former ally by throwing in completely with the Axis, the worst-case scenario for the British, instead choosing only to bomb Gibraltar and then sever diplomatic relations."

According to some sources, Admiral Darlan actually wanted to ally with the Axis after Catapult, and it was Hitler who refused, for whatever reason. Maybe the British had a big stroke of luck there.

ajgyles:

France was never going to be a very reliable ally to Germany but refusing would be extremely stupid, possibly too stupid even for Hitler.

I opine that the invasion of Norway was not an amphibious operation in the sense that Sea Lion would have been. There were no opposed landings, indeed no "landings" at all in the sense of trying to get boats full of infantry onto an open beach. The Germans sailed right up to the quaysides in an assortment of ports - Norway does have a lot of good ports - and just unloaded their infantry down the gangplanks, relying on speed and surprise to get them past the coastal artillery. Where they were effectively opposed - the Oslo fiord - they were repulsed; in the case of Kristiansand they were twice made to retreat, and only got in to the harbour when the chance resemblance of a signal flag to the French naval ensign made the fortress commander think that Allied reinforcements were arriving, and cease fire. The Germans were relying on total strategic surprise and the unpreparedness of a country which was neutral so far as it knew; and while they had both, it was still touch-and-go for them and they got some good lucky breaks. None of that would have applied across the Channel or provided them with useful experience for invading the Isles.

(My main source here is "9. april - time for time", Alfred Jacobsen, which to the best of my knowledge is only available in Norwegian, sorry.)

The Germans were relying on total strategic surprise and the unpreparedness of a country which was neutral so far as it knew; and while they had both, it was still touch-and-go for them and they got some good lucky breaks.

THis is pretty much the story of the entire first 2 years of the war. Arguably for Japan too.