In 1940, the French fleet was the 4th-largest in the world, and the French defeat raised the very real possibility that it would fall into German and Italian hands, tipping the balance of naval power in Europe. The French were determined that this would not be allowed to happen, and evacuated as many ships as they could to their African colonies. But Churchill wasn't willing to accept their assurances, and on July 3rd, took more forceful measures to make sure the French ships didn't become a threat to British interests. Ships in British ports were seized, while a task force arrived off Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria, with an ultimatum for the ships there to either join the British or be sunk. The French chose the latter option, and the British opened fire, sinking two battleships and badly damaging a third, Dunkerque.

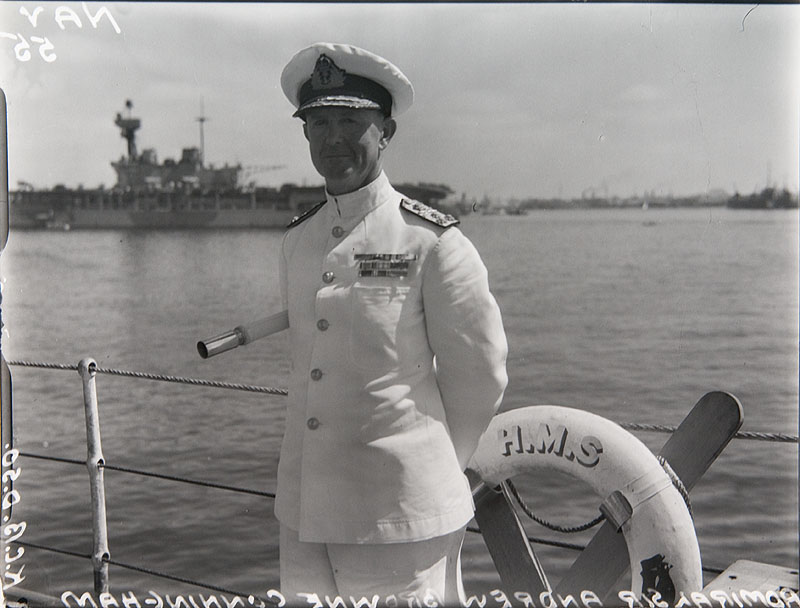

Andrew Cunningham

This caused major problems for the last major French force within easy reach of the British, Force X at Alexandria, sent to aid the British in protecting the eastern Mediterranean. The British commander, Andrew Cunningham, received orders to give his French counterpart, Rene-Emile Godfroy, the same ultimatum that had been delivered at Mers-el-Kebir, but the two men agreed that no actions would be taken that day, despite both sides receiving orders over the radio that would have caused a massacre. Tensions remained very high on the 4th, and Cunningham ordered his ships to stop aiming at the French, while Godfroy insisted that his crews adhere as closely as possible to normal peacetime routine. The sight of French sailors scrubbing the decks, painting, and even swimming did as much as anything to lower the risks of shooting breaking out.

By the evening, the two commanders had negotiated a deal. The French ships would not be harmed, and would remain in the possession of their crews, but they would be drained of fuel and the breechblocks of their guns would be stored in the French consulate ashore. Neither Darlan nor Churchill was particularly happy with the outcome, but the agreement held until 1943, with the only incident coming in mid-1942, when Axis successes in North Africa threatened Alexandria itself, and it was unclear if the French ships would follow the British into the Red Sea or be scuttled. The British victory at El Alamein resolved the problem, and Godfroy finally agreed to join the Free French the next year, bringing with him the elderly battleship Lorraine, four cruisers, three destroyers and a submarine.

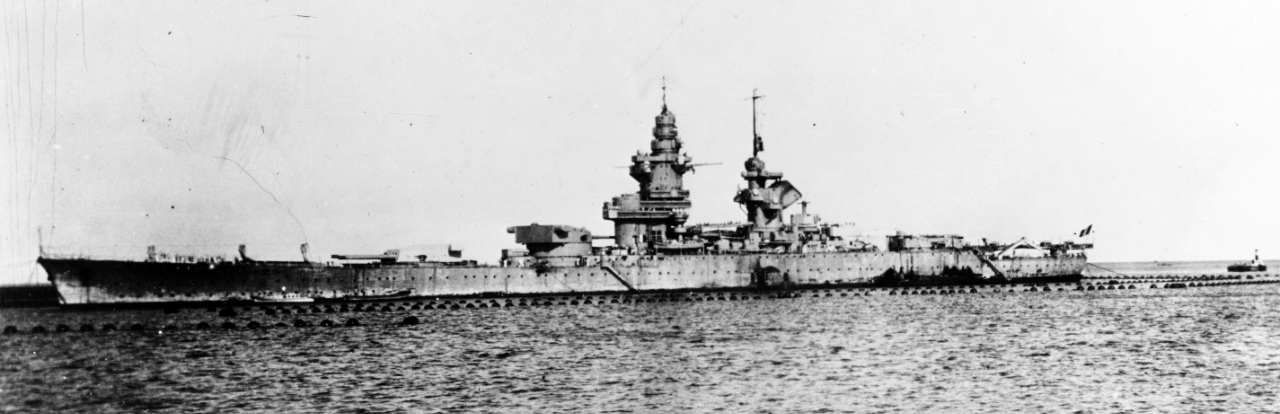

Richelieu at Dakar

But even with the ships in Alexandria neutralized, the most modern French battleships still remained at large, Richelieu at Dakar in West Africa, and Jean Bart in Casablanca. The later ship was not considered much of a threat, as she was far from complete after her narrow escape from the Germans, with only one turret installed and no ammunition for it. Simple surveillance by a few ships in the area was sufficient. Richelieu was a different matter, and the original plan had been to send the ships that had struck Mers-el-Kebir to deal with her. This was scuttled by the need to attack Dunkerque a second time, and a scratch force composed of carrier Hermes and cruisers Dorsetshire and Australia was dispatched, arriving on July 7th. They issued an ultimatum similar to that given at Mers-el-Kebir. The French refused, and planned to sortie with Richelieu the next morning in an attempt to sink Hermes. Only 8 shots were available, as the mechanism to bring charges up from the magazines was incomplete and doing so took about 15 minutes each. That night, the British sent in a motorboat armed with depth charges to disable the battleship, and when that failed, launched a dawn strike with Swordfish from Hermes. Five of the six torpedoes missed, but one hit near the stern, causing great damage due to the shallow water, which magnified the effect of the hit. Richelieu was clearly going to be out of action for a long time, particularly as Dakar had nowhere near the facilities normally required to repair such damage.

Even after the shooting stopped in July, tensions between Britain and France remained high. Britain initially included France, even the unoccupied zone run out of Vichy, in its blockade of the continent, angering the French government, although they retreated somewhat in later months. The attack on Mers-el-Kebir greatly hindered the growth of the Free French under Charles de Gaulle, as most French soldiers in British territory preferred to return home rather than carrying on the fight with their former allies. The British, meanwhile, were preoccupied with the German air campaign at home and the looming threat of invasion, as well as the war with the Italians for control of the Mediterranean. France only returned to the forefront in late August, when the governor of French Equatorial Africa declared for the Free French, the first overseas territory to rally to De Gaulle. Both sides responded, De Gaulle persuading Churchill that he could bring Dakar onboard with minimal bloodshed, and Darlan dispatching an expedition to bring Equatorial Africa back into the fold. This force, three light cruisers and three big destroyers, was allowed past Gibraltar because the commander there had not been informed of British plans to seize Dakar, and the ships safely reached their destination. The ships, escorted by another cruiser already at Dakar, then sortied to Libreville, but they were intercepted by the British, and two of the cruisers were escorted to Casablanca and out of the fight.

A rangefinder for the French coastal batteries at Goree, near Dakar

On September 23rd, the Franco-British force arrived off Dakar, and De Gaulle's efforts to convince the authorities to join him failed completely. The British then tried to intimidate them with the naval force, built around battleships Barham and Resolution, carrier Ark Royal and a number of cruisers, but fog forced them close to shore, where French coastal batteries could return fire. Cruiser Cumberland was badly damaged, and the Free French began to land that afternoon, while destroyer L'Audacieux tried to sortie and was driven ashore by 8" shells from Australia. The troops ashore proved remarkably ineffective, and the next day, the British battleships again attempted to bombard the harbor. Richelieu got into the battle, but defective shells kept exploding in the barrels of her guns, limiting her effectiveness. Fortunately, British gunnery was not particularly good, and she took only a single hit. The next day, the British troops, held in reserve, were ordered ashore, but as Barham and Resolution reached their bombardment stations, submarine Beveziers managed to torpedo the latter ship, opening a massive hole in her side and putting her completely out of action. The British attempted to carry on the bombardment with Barham and his cruisers, but French gunnery was good, hitting both Barham and Australia, and the operation was called off. Their victory greatly bolstered French morale, and while they did retaliate by bombing Gibraltar, they remained technically at peace with Britain.

The French spent the next two years walking a diplomatic tightrope, trying to get the best conditions they could out of Germany while not annoying the British too much, while the Germans worried about the Empire and fleet defecting to the Free French and the British fretted about the potential those could have if they went fully over to the Axis. Occasional clashes over shipping took place, but France found itself under the greatest strain in mid-1941, when a coup in Iraq sparked a British invasion of that country. The Iraqis appealed to Germany and Italy for help, and the Germans demanded the French let their aircraft refuel in Syria. The British, fearful that recent German successes in Greece might be repeated in Syria, invaded both that country and Lebanon in June. The French forces in the area fought back, both on land and at sea, and during a clash off Sidon, a pair of French destroyers badly damaged destroyer HMS Janus. The French squadron fired off enough ammunition that a resupply run from Toulon was authorized, but the British intercepted the destroyer in question and sank her with a Swordfish torpedo attack. She radioed for help, prompting a second clash between the French and a small British squadron, which ended with no casualties to either side. A third took place a few nights later, when the French squadron finally withdrew from Beirut, eventually returning to Toulon. Darlan discussed sending reinforcements aboard Strasbourg and the rest of this fleet, but this plan never took place, and the French authorities finally capitulated in mid-July.

For the next year, things were quiet, and it wasn't until November 1942 when events finally forced the French out of their uncomfortable neutrality. But before I can tell that story, we'll need to take a look at the wider war in the Mediterranean.

Comments

Maybe I'm just a tard, but the skipping back and forth between years/plot threads makes some of the month-only dates a little confusing.

I had no idea there was quite this much combat!

Unfortunately, there are certain posts which are really hard to structure, and this was one of them. I'll see if I can clean that up.

Cunningham tells the Alexandria story slightly differently in his autobiography A Sailor's Odyssey. He says he and Godfroy had provisionally agreed to the conditions you describe on the evening of the 3rd, but then overnight Godfroy received full details of Mers el Kebir, and was making preparations to put to sea and/or fight on the morning of the 4th. Cunningham ordered his fleet to turn its guns on the French squadron, and his captains to go aboard and negotiate separately with their French counterparts. It was only after a conference of his captains that Godfroy conceded on the afternoon of the 4th.

The British admiral at Dakar was John Cunningham, no relation (afaik) to Andrew Cunningham at Alexandria. Both, confusingly, were C-in-C Med during the war and subsequently First Sea Lord.

The attack on Mers-el-Kebir greatly hindered the growth of the Free French under Charles de Gaulle, as most French soldiers in British territory preferred to return home rather than carrying on the fight with their former allies.

So this refers to, eg. all the French soldiers evacuated from Dunkirk who then decided to go back to occupied France and the Germans made them POWs?

Pretty much. I don't think they expected to be made POWs.

@Alan

I checked several sources on the stuff in Alexandria, and this is what I came up with. Interesting that Cunningham has a different version. As for John Cunningham, that was an unforced error on my part. I've solved that by switching to a generic.

This series on the fate of the French fleet (I think of it as The Fate of the Furious) is an excellent recap of the entire drawn-out, poorly planned, sorry-as-fuck affair. I realize that you can't judge people of the past based on the context and knowledge of the present, but come on. From Churchill's desire to look like a badass to the French commanders who spent three years deciding who to fight for/against, no one comes out of this mess looking good. It's been said about novel writing that you're not the writer your novel needs you to be until you finish it, and I suppose that's true about fighting a war, too.

What I've never read about is how the French fleet supported itself while in colonial ports. Everyone has to make a living. Who paid the sailors' salaries? Who fed them? Who paid for fuel and ammo? Did they maintain a CAP over the port? Where did the avgas come from? How did they maintain all these ships? How did they keep the sailors and support personnel from running away to join the British, or even the circus?

You have a terrific site, Bean, and I'm enjoying catching up on your older posts.

The French fleet in colonial ports did not need to support itself, it remained part of the French state (Vichy) and was paid for by the mainland French government. Remember that France had been invaded but not entirely occupied, there was still a functioning French government.

The Brits agreed that civilian merchant trade could continue between mainland France and French colonies. In theory the Royal Navy inspected the ships to make sure military supplies weren't being transported, in practice the RN had more important things to do and some got smuggled in. The Germans were often more obstructive about preventing repairs and resupply of French warships.

The existence of a mainland French government made joining the Free French a tough decision, and most of those who wanted to run away and join the Allies did so in 1940. Those in colonial ports stayed loyal to the mainland French government usually until their commands changed sides.

Three Republics One Navy by Anthony Clayton is a good short guide.

Thanks, Hugh. That sounds like a good book.

I had assumed that the Vichy government mostly didn't function, except for rounding up Jews, gypsies, communists, and other people they didn't want and handing them over to the Nazis. I had also assumed that Vichy's GDP didn't amount to much after losing half their country. Now I'm looking forward to reading Three Republics One Navy.

Seventy-nine years later and WW2 is still fascinating.