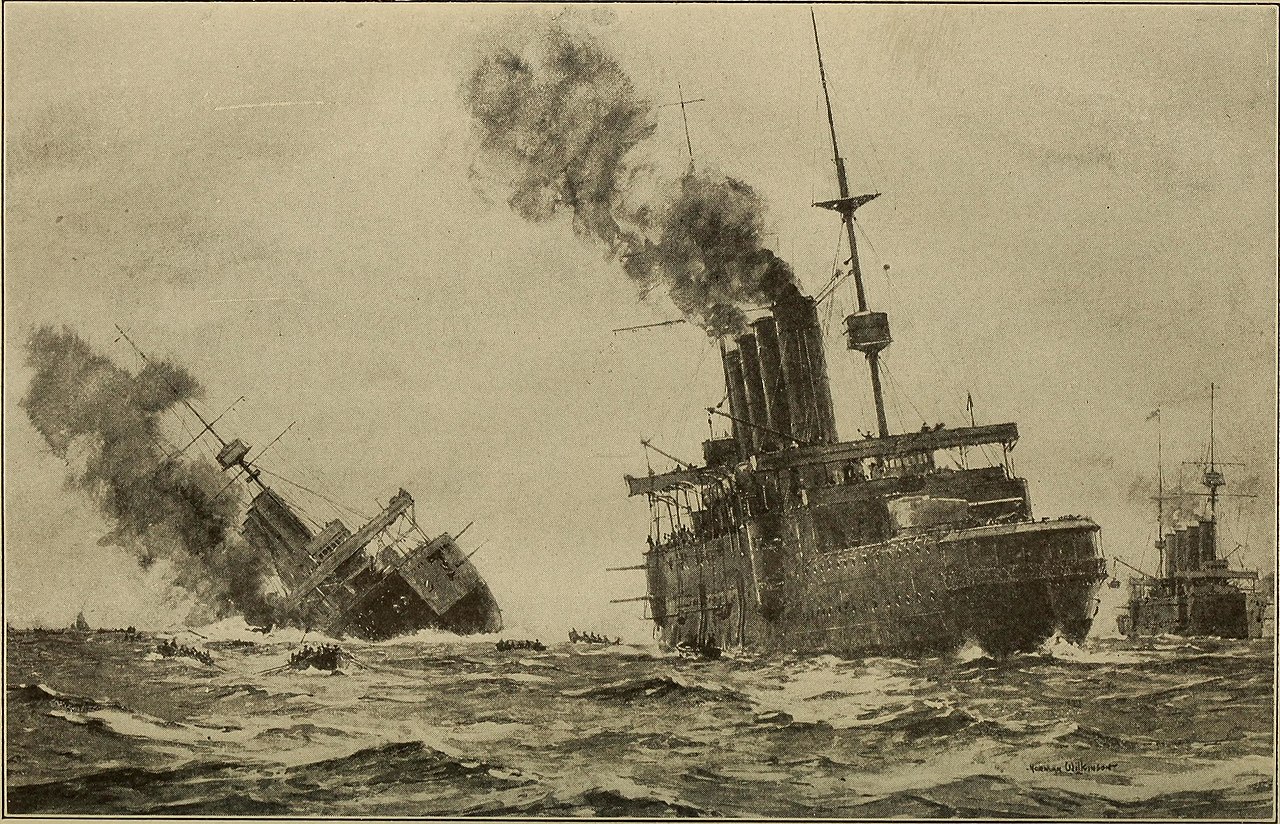

In the aftermath of the British victory at Heligoland Bight, the Kaiser chose to keep the High Seas Fleet immobile, relying instead on submarines. These first struck on September 22nd, when U-9 came across three obsolescent British armored cruisers on patrol off the Dutch coast, Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy. These ships, part of what was known as the the "Live Bait Squadron", were moving at relatively low speed when Aboukir was torpedoed. Hogue and Cressy hove to to recover survivors, but they were swiftly torpedoed in turn. All told, only 837 of the 2,296 men aboard the three cruisers survived, and the British swiftly withdrew anything bigger than a light cruiser from the waters near Germany.

Aboukir sinking

Even this wasn't enough, as the primitive submarines of 1914 could reach across the North Sea, as demonstrated when U-9 added armored cruiser Hawke to her score on October 15th. Jellicoe became increasingly concerned with the security of the Grand Fleet's base at Scapa Flow, and began to keep his ships at sea as much as possible. This quickly wore out ships and men and forced them to spend a lot of time coaling, so he decided to withdraw to Lough Swilly in Ireland. But while this was enough to deal with the submarine threat, the Germans had other weapons they could make use of.

In mid-October, three minelayers set out. Two, dispatched to mine the approaches to the Firth of Forth on the eastern coast of Scotland, turned back when they intercepted heavy British wireless traffic, but the third, the converted passenger liner Berlin, persevered. She has been ordered to lay her mines in the Clyde on Scotland's west coast, but the lack of lights and heavy wireless traffic made this too hazardous, so her captain instead chose to place his deadly payload in the shippping lanes near Lough Swilly. While he was aiming for merchant vessels, he got much more. On October 27th, while conducting firing practice, the new dreadnought Audacious struck one of these mines. Because she was turning, it detonated aft on her port side, where her protection was weakest, and the port engine room flooded almost immediately. The immediate belief was that she had been hit by a submarine, and her Captain ordered full speed (9 kts) with the starboard engine and turned towards the coast, hoping to make the 25 miles and beach her before she sank. Unfortunately, she only made about 15 of the 25 miles before flooding shut down her remaining engines.

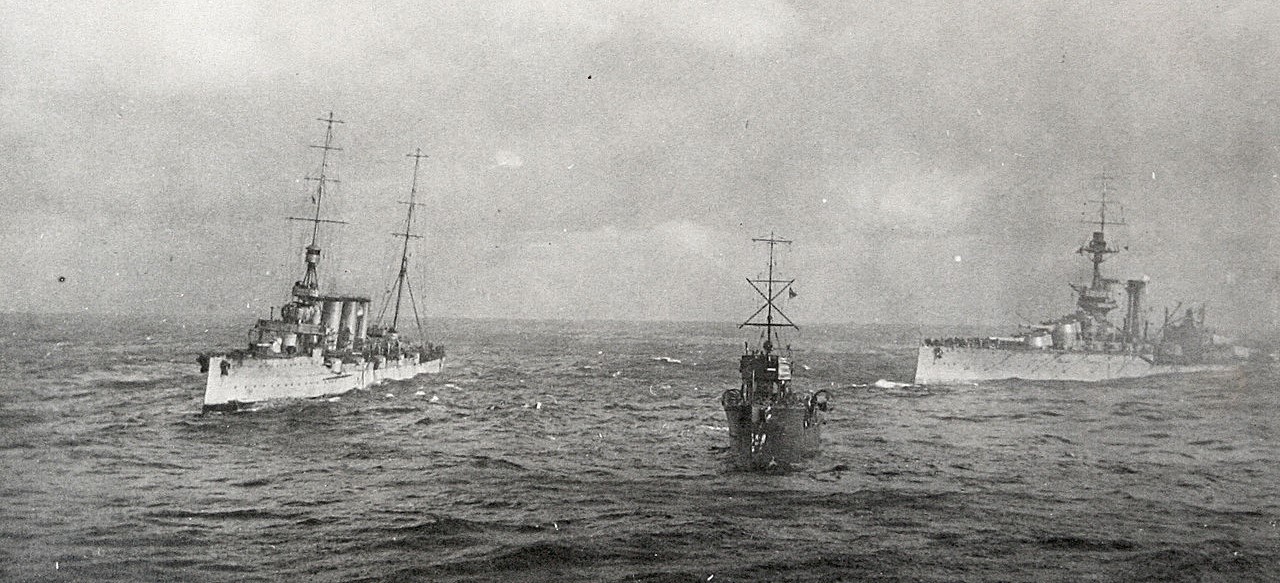

Liverpool attempts to tow Audacious

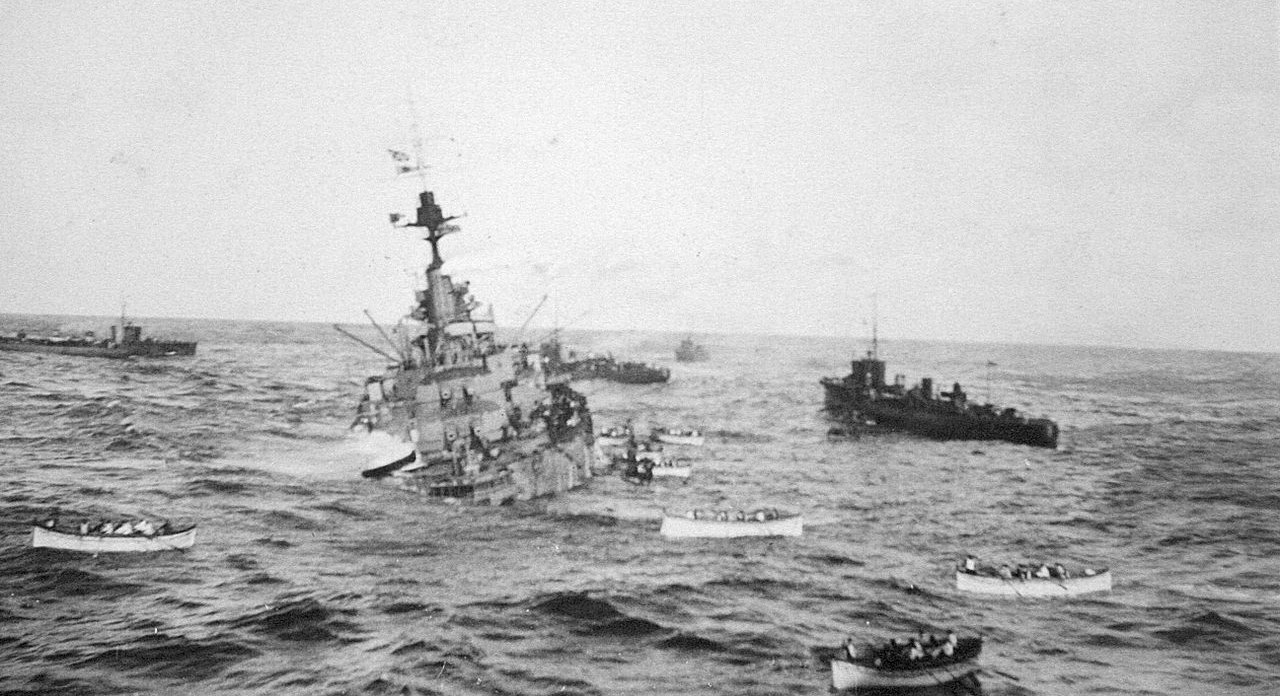

The other battleships had fled in fear of the notional submarine, but Jellicoe had dispatched tugs and destroyers to assist, and the passenger liner Olympic had arrived on the scene as well. Several attempts by various ships, including Olympic, were made to take the stricken battleship in tow, but none were successful, and the crew was evacuated. 12 hours after the mine went off, she rolled over and exploded, probably due to a shell falling out of a rack. A fragment from the battleship struck a petty officer aboard nearby cruiser Liverpool, the only death in relation to the loss of Audacious.

The crew of Audacious takes to the boats

Concerns about the narrow margin of British superiority prompted the Admiralty to conceal the loss of Audacious from the Germans. There was no way this could be sustained for more than a few weeks given that the passengers on Olympic, including a number of Americans, had witnessed the sinking, but the Admiralty chose to maintain the pretense through the end of the war, damaging public trust in its official statements.

The day after Audacious went down, Jackie Fisher returned to the Admiralty, replacing Prince Louis of Battenberg, who had resigned due to his German background. The Germans greeted him with the first foreign attack on mainland Britain since 1797, when the French landed a force at Fishguard in Wales. The operation had begun as a plan to lay mines off the north coast of England, in hopes of evading the watchers around the ports that had thwarted earlier efforts, and it was to be covered by the battlecruisers of the First Scouting Group, which were eventually authorized to bombard the town of Yarmouth during the operation. The battleships would go to the edge of Heligoland Bight, but no further, which made them poorly placed to intervene should the British catch Hipper.

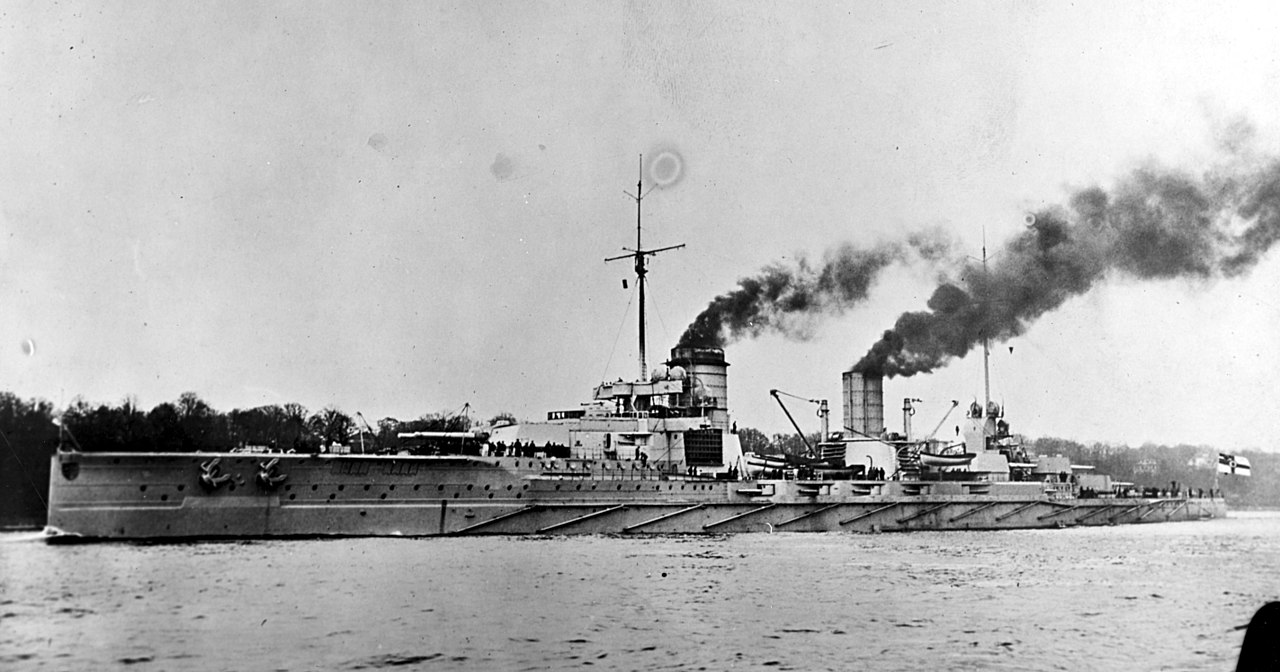

Seydlitz

The German force crossed the North Sea on the night of November 2nd/3rd, arriving off the coast at dawn. The British policy of dousing lights and removing navigational aids paid off, and they were badly out of position, delaying the operation by an hour. Yarmouth itself lay wide open, with only an old torpedo gunboat and some obsolescent destroyers, but these were enough to foil the German plan. Torpedo gunboat Halcyon, at sea to look for drifting mines, encountered the German battlecruisers, and Hipper gave orders for Seydlitz to open fire. Thanks to poor communications, two of her consorts did likewise, and the muddle of shell splashes rendered spotting impossible. Destroyer Lively then intervened, drawing a smokescreen around Halcyon and darting in and out of it to keep the Germans occupied. Hipper realized that shooting at the destroyer was a waste of resources and turned for home, his ships ineffectively flinging a few shells towards Yarmouth, none of which did any damage.

The British were confused by the operation, although Admiral Tyrwhitt, commanding the Harwich Force, ordered a group of ships at sea to intercept after picking up a message from Lively. They spotted the Germans, and tried to draw them into a chase, but Hipper was focused on getting home and ignored them. On the whole, the operation hadn't been a huge success. The British got a propaganda victory, while the Germans realized that armor-piercing shells weren't the best option for shore bombardment. Matters were made worse when the armored cruiser Yorck, deployed as part of the High Seas Fleet, blundered into a minefield on the way back and sank. The British, meanwhile, recalled their heavy ships to prevent a recurrence, with Beatty's battlecruisers being based at Rosyth, on the Firth of Forth, while Jellicoe's ships returned to Scapa and pre-dreadnoughts being stationed on the North Sea coast.

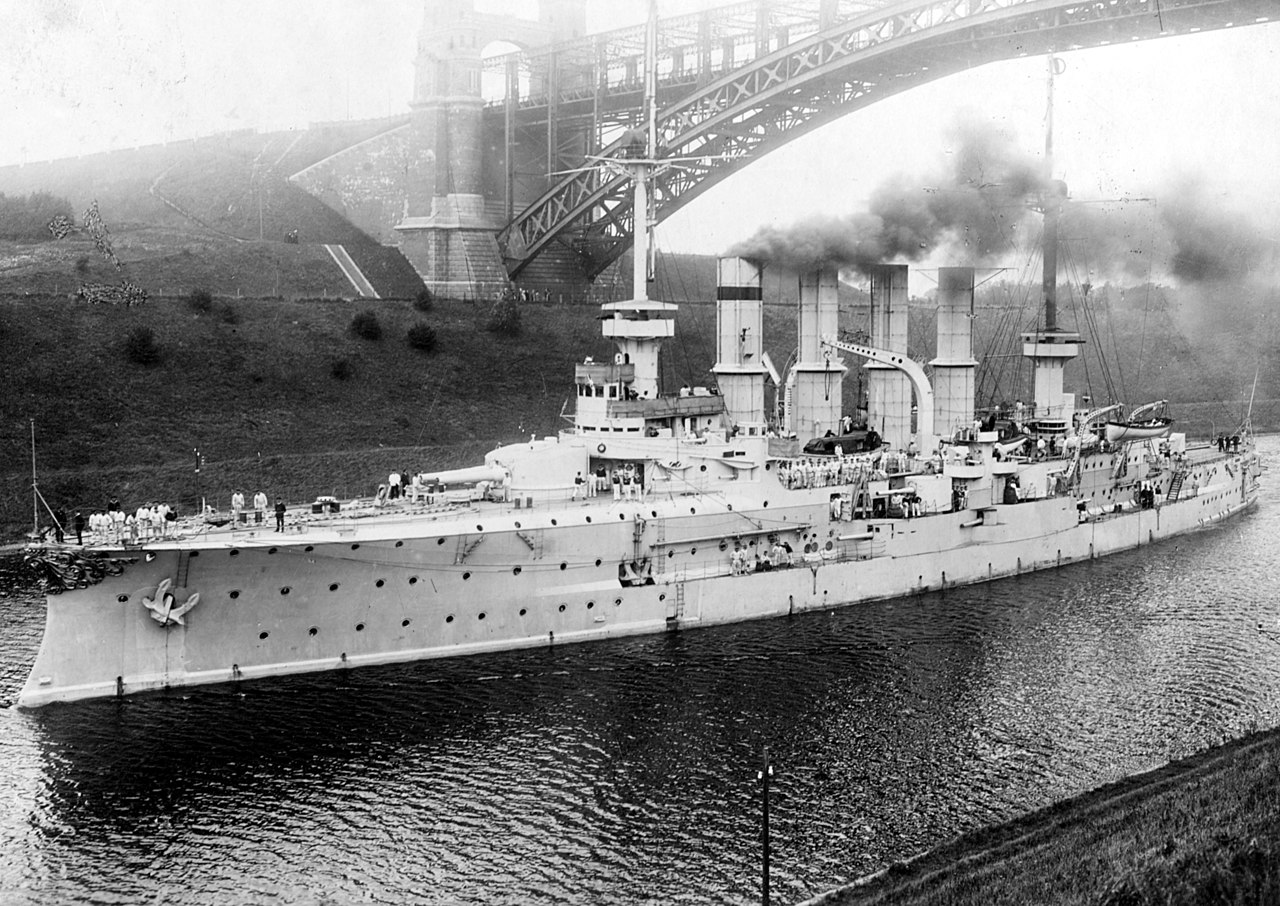

Yorck in happier days

Things were made worse by the arrival of news of the defeat of a British force off Chile by the German squadron under Maximilian von Spee. Dealing with this was a job for the battlecruisers, and Invincible and Inflexible were dispatched to the South Atlantic, cutting Beatty's edge over Hipper. The British, facing the loss of the Belgian channel ports, also became concerned over the potential threat of a German invasion, not yet realizing how difficult that would be.

But the British were about to get a priceless advantage in the struggle for control of the North Sea, which would keep the Germans from surprising them again until very close to the end of the war. It's a topic that deserves a closer look before we continue the story of the battle for the North Sea.

Recent Comments