Today marks the 76th anniversary of one of the most important days in the demise of the battleship. While the Pearl Harbor attack gets much more attention, the sinking of Force Z, the battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse, at the hands of the Japanese was in many ways more influential. Both Pearl Harbor, and Taranto before it, were made on ships that were at anchor and unaware of the attackers. Force Z was at sea and alerted to the possibility of attack, a condition that many believed would keep it safe.

Prince of Wales in Singapore Harbor

Repulse and Prince of Wales were dispatched to Singapore by Churchill in October of 1941 in an attempt to deter the Japanese from starting a war.1 The two ships entered Singapore with four destroyers2 on December 2nd. They were greeted with a blaze of publicity unusual during the war.

Repulse leaving Singapore

On December 8th,3 the Japanese struck. The British, like the Americans, were caught flat-footed, and the use of the ships was hampered by a lack of overall strategy on the part of the defenders of Malaya.4 The ships could have been used as a fleet in being and would have contributed significantly to the defense of Java later. However, they were instead sent north in an attempt to sink the Japanese invasion fleets off Singora and Kota Bharu. Force Z, under the command of Vice Admiral Tom Phillips, departed on the evening of the 8th, intending to attack at dawn on the 10th.

Admiral Sir Tom Phillips

Phillips had just come from a staff position at the Admiralty, and was not highly regarded as a fleet commander. His plan relied on surprise and air cover, but he was informed just before he sailed that no air cover would be available. Despite this, he pressed on. On the 9th, Force Z spotted several airplanes overhead, and Phillips, believing surprise had been lost, turned back. In fact, the airplanes didn't sight the British, but several Japanese submarines did. Late on the 9th, Phillips received a message that the Japanese were landing at Kuntan, only 150 miles from Singapore and astride the supply lines to the armies in northern Malaya. He diverted his ships to investigate, hoping to salvage something from the mission. Unfortunately, the message was erroneous and there was no landing.

G3M "Nell"

At this point, things went from bad to worse. Phillips maintained radio silence, apparently having confused 'no fighters available over Singora or Kota Bharu'5 with 'no fighters available at all'. He also assumed, on the basis of previous war experience against Germany and Italy, that the 400 miles separating him from the Japanese naval air bases in what is now Vietnam protected him. He only expected to have to deal with Army airplanes based in southern Thailand, airplanes neither trained nor equipped for anti-ship work.

G4M "Betty"

Unfortunately, the Japanese had achieved extreme range in their airplanes, mostly by building them out of tinfoil and tracing paper. Later in the war, this would bite them, but Force Z didn't have enough AA firepower to show the drawbacks of their design choices. The Japanese strike was launched before the ships were spotted, so the first attack wave was overhead within an hour of the first sighting. However, they arrived spread out and low on fuel, preventing a coordinated attack.

Prince of Wales (top) and Repulse during the first high-level bombing attack

The Japanese bombers were twin-engined G3M 'Nells' and G4M 'Bettys', a mix of level bombers attacking from about 10,000 ft and torpedo bombers. The first wave of nine level bombers scored one hit on Repulse, but the 550-lb bomb didn't do much damage. The British then had a half-hour respite before the next wave. The next nine airplanes were torpedo bombers, and they focused on Prince of Wales. Only one torpedo hit, but it was enough to doom the battleship.6

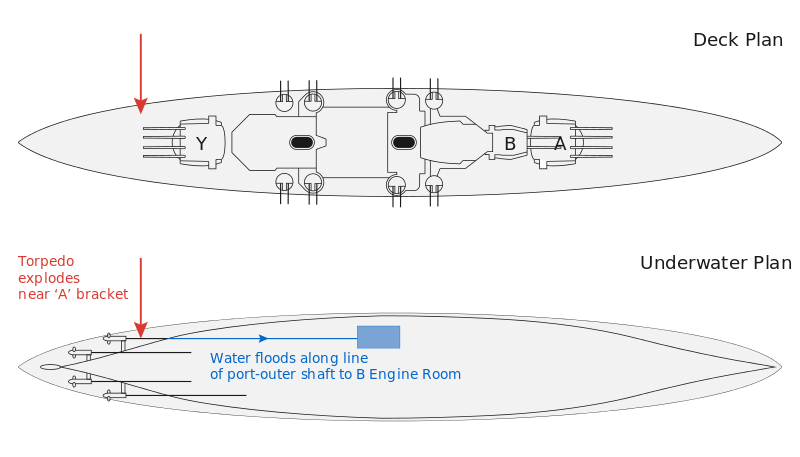

Damage to Prince of Wales from the first torpedo hit

The weapon struck Prince of Wales near the aft funnel on the port side. The explosion bent the port outboard shaft, which continued to turn, ripping open the shaft glands and allowing water to flood into both engine rooms on the port side, as well as one of the two aft boiler rooms. Within 10 minutes, the ship was listing 11.5 degrees. The steering gear was knocked offline, and both port shafts were rendered inoperable. The hit also caused serious problems to the ship's communications and electrical systems. At one point, 7 of the 8 5.25" turrets were offline, although several were restored to at least limited function during the battle.

Prince of Wales and Repulse under air attack, with an escorting destroyer in the foreground

The next two waves attacked Repulse with both torpedoes and level bombs, but her captain, W. G. Tennant, skillfully avoided all of the Japanese munitions. As he did not know the situation on the flagship, Tennant finally broke radio silence and asked for fighter cover, which was, for once in Malaya, available quite quickly. Unfortunately, it wasn't quite quickly enough.

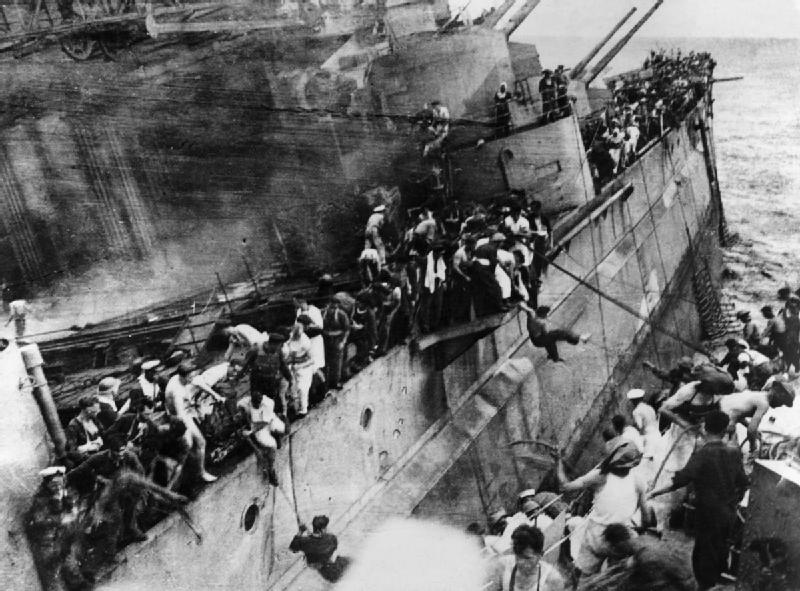

Survivors being taken off Prince of Wales by an escorting destroyer

The next Japanese torpedo attack was beautifully executed, catching Repulse part-way through a turn and hitting her once, although the old battlecruiser withstood the hit quite well. Her consort took three more hits during this attack, farther reducing her buoyancy and speed. Despite Tennant's best efforts, Repulse soon took three more torpedo hits, and he ordered his men over the side. Prince of Wales was able to put three secondary turrets into action to oppose the last level bombing attack after Repulse sank. She took one hit, which failed to penetrate the armored deck. Half an hour later, it was obvious that the damage was mortal, and she, too, was abandoned. Three hours after the first Japanese attack, both ships lay on the bottom of the sea. The air cover that Repulse had called for arrived overhead just in time to see Prince of Wales go down.

Prince of Wales sinking

Ultimately, the Japanese aviators achieved 8 torpedo hits from 49 dropped, an incredible number, and lost only four airplanes. Their performance spelled the beginning of the end for the big-gun warship as the primary instrument of sea power, although they wouldn't be totally superseded until the development of all-weather carrier aviation after the end of the war.

1 Unfortunately, it was too little, too late, as large portions of the Japanese military had already decided on war. ⇑

2 Initially Electra, Express, Encounter and Jupiter, but the much older Tenedos and Vampire were substituted for the last two when they were in the yard and unable to sortie in time. ⇑

3 Singapore is east of the international date line. When I was there, I was a bit surprised when I heard them use the 8th as the date of the start of the war, but I'm going to use east longitude dates here. ⇑

4 I'm not going to go into detail here, but the defense of Malaya was handled spectacularly badly. In a lot of ways, the RN came out of it looking best, and that's despite the events I'm talking about here. ⇑

5 In southern Thailand and northern Malaya where the Japanese had initially landed. ⇑

6 Some accounts say two or even three hits in this attack, but inspection of the hull in 2007 proved there was only one. ⇑

Comments

I seem to recall other accounts of the battle suggesting that one of the ships (Prince of Wales, I think) was experiencing malfunctions in its AA fire control, possibly due to the local heat and humidity. Is this one of those stories that may not be true, or do you think it didn't matter very much?

Prince of Wales had at least some radars out of action during the battle, although exactly which ones has proved rather difficult to pin down. I'm slightly disturbed, as it should have been in at least two of my books.

Ultimately, it was cut for length and narrative reasons. Based on the sources I have on hand, I could fairly easily expand this to something rivaling the Jutland or Iowa series. But I really didn't want to do that, and that meant leaving things out that didn't fit.

Also, HACS (the British medium fire-control system) was so bad that radar wouldn't have been enough to save the ships, or even probably inflict meaningfully more casualties on the attackers.

Is "keep Force Z as a fleet-in-being" an option that was seriously considered, or just hindsight? It feels like a bit of a stretch to expect a couple of available capital ships to stay out of the Malaya fight, especially that early in the war when the strategic situation was not as clear.

Was that decision all on Phillips, or was he pressured into it? Could he have made no effort to support Malaya and kept his job? Otherwise the judgement on him seems a bit harsh - after that point was his only real blunder failing to call for air support as soon as he came under aerial surveillance/attack? Having decided to sortie at all, the plan, and subsequent decision to turn back, as well as the attempt to seek a target of opportunity, seem reasonable. Was there another mitigating factor?

I also found it interesting that the actions of Repulse and Tennant are called out as particularly skillful - was Prince of Wales fought poorly? From the information here it sounds like they were more unlucky than anything, taking a torpedo in the exact wrong spot. Can't fault seamanship for a design weakness.

That's a good question. On one hand, the Navy simply saying "you're on your own here" was pretty much unthinkable. On the other, squandering two capital ships for the sake of honor is pretty absurd. The whole of the Malaya campaign was like this, actually. Singapore had to be held because of the prestige of the British Empire, so nobody bothered to say that they couldn't do it with the available resources. On the gripping hand, Phillips didn't exactly make the best use of the ships.

Not reevaluating after he lost air support was a serious mistake. A lot of his actions were just a bit off. He didn't pay attention to the submarine threat (one Japanese submarine launched a torpedo attack that the British just didn't notice), he maintained radio silence even when it didn't make sense, and he wasn't well though of as a sea officer.

This is another thing I could do a full post on. AIUI, PoW's captain chose to turn broadside instead of trying to comb the torpedo tracks, essentially choosing AA firepower over trying to dodge. This may have been based on British AA experience in the Mediterranean. The British system at the time was pretty bad, but they may have deluded themselves into not noticing that. They were definitely unlucky in the location of the torpedo hit, but I'm also not sure how much of that was the designer's fault, and how much was just the inevitable vulnerability of the shafts.

All of that said, Tennant is generally regarded as one of the better British naval officers of the war, and his handling of Repulse during the action usually draws praise.

Phillips was of the opinion that capital ship AA was very capable of protecting ships from torpedo attack, plus he (and the RN) were totally unaware of just how good Japanese aerial torpedo bombing was (not to mention the range). Several of the British accounts, for instance, express surprise at how high and fast the Japanese bombers were when they dropped torpedoes.

That said, POW had a very unlucky hit -- it's pretty much impossible to protect rudders and propellors from torpedoes, but bending a shaft led to huge flooding issues on top of that. And Repulse did pretty good at combing torpedoes; it's very possible that she might have gotten off entirely had she been a bit luckier, or had a few more torpedo bombers gone after POW again. We tend to think of Force Z's demise as inevitable, but it really wasn't - it was a combination of quite a few factors.

Lack of air cover was a definite problem - so was the lack of British intelligence on the Japanese - so was ship handling - so was lousy British AA design (to be fair, it was probably perfectly adequate against planes from 1935-38 and the state of air design was rapidly advancing during those years!) - so was the lousy state of British intelligence about the threat - and not having a carrier along was also a big big problem.

The root of the matter was that British strategy in the Far East had been based on a fantasy for twenty years: the fantasy that the Royal Navy could send substantial strength to the Far East if Japan threatened, when in fact Japan was only ever likely to attack if the Royal Navy were occupied in home waters by a European power. The British didn't want to pay for a fleet big enough to hold European waters AND fight the Japanese at the same time, and didn't want to admit that (particularly not to Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore). Denying truth led to all sorts of down-the-road effects, most of which were not good.

Losing four capital ships in the Med in the fall of 1941 (Barham and Ark Royal sunk, Queen Elizabeth and Valiant mined in Alexandria harbor) also made a difference; those ships could have been deployed fairly quickly to Malaya if necessary. (As it was the British had a substantial fleet in the Indian Ocean by April 1942 -- just in time to run away from Nagumo's First Carrier Fleet, which was ANOTHER thing the British were totally unprepared for, but they could have put up quite a fight against anything else the Japanese were prepared to commit to the East Indies.)

Churchill's idea was that a fast British battle squadron could paralyze Japanese shipping by the threat of their attacks, much like the Tirpitz exercised a similar restraint on British shipments to Russia. This might have worked with sufficient air cover, except for geography (Malaya was at the periphery of Japanese interests; you'd have had to base Force Z out of the Philippines or Russian ports to be nearly as close to major Japanese shipping lines as German units were to the North Atlantic), and it ignored the Japanese tendency to charge ahead and do stuff anyway (but then that was not completely clear at this point in the war, either, so there's some excuse for Churchill).

Tony, an excellent summary. One quibble:

This is mostly true, but the full truth is considerably more complicated. In 1921, the Singapore Strategy made sense. There were plenty of ships available to send given the strategic situation the British expected to face. German rearmament made this a lot more precarious. What really pushed it over the edge was Italian entry into the war after it was obvious France was doomed, combined with the loss of the French fleet to the allies. If the Germans hadn't gotten inordinately lucky in France, Italy probably would have stayed out, and then the British don't have a whole bunch of ships tied up in the Med.

The bigger issue was that there had been a long-term policy of not giving Singapore the resources needed to defend itself. The naval base was not up to supporting the fleet that was planned in wartime, and the other services didn't get the resources they needed to make their plans work, either. I read a very interesting book on this earlier in the year.

The idea behind having a powerful fleet wasn't so much the same type of paralysis as Tirpitz caused as it was to make it prohibitively expensive to go after the Malaya-East Indies region. If Force Z had survived, the consequences for the conquest of Indonesia would have been huge. That was a near-run thing anyway, and the added pressure of two capital ships would have slowed them down significantly. And remember that the war started because the Japanese wanted oil from Sumatra and Borneo. Everything else was to support that conquest.

"If Force Z had survived, the consequences for the conquest of Indonesia would have been huge. That was a near-run thing anyway"

But at the time the decision was made to deploy force Z to defend Malaya, it was not known whether Malaya would be a close run thing. Keeping them out of the fight would be more or less admitting that Malaya (and Singapore) would be lost, and I wonder if it's fair to expect that only a few days after Pearl Harbor.

"... and he wasn't well though of as a sea officer." "All of that said, Tennant is generally regarded as one of the better British naval officers of the war..."

What I was poking at was that the "conventional wisdom" of these officers' reputations feels like it's doing a lot of work here. This is your own fault for writing a good Jutland series that made it clear that "conventional wisdom" about and from British naval officers should perhaps not be taken at face value!

"If the Germans hadn't gotten inordinately lucky in France"

You think the German invasion of France was a lucky stroke? This goes against my normal received wisdom about early war land operation--got an interesting source here?

@gbdub

A valid point. The whole Malaya campaign is a bit like a Greek Tragedy from start to finish. Everyone is ultimately doomed due to vast forces beyond anyone's control, but you still are thinking "what if someone had acted differently?"

Blast it, man! I'm not made of time! I have other things to write about.

I've actually gotten into an argument elsewhere about this, and the other guy (who I respect as being generally well-informed and sane) is saying good things about Phillips. My best source is not complimentary towards him, and I'd rather not spend the time required to sort this out right now. The above is based on my best sourcing and knowledge, and I'm not going to spend the time to follow all the rabbit trails right now.

@Andrew

Fall Gelb should have been a disaster, and it was only the fact that the French were massively disfunctional that let them get away with it. There's a lot on this in the wonderful A Blunted Sickle alt hist.

Yes, in 1920 Britain could comfortably send lots of ships to the Far East without fear of European threat, but it was reasonably obvious that this was a temporary situation (eventually some European power was going to build a fleet that at least made sure Britain kept its fleet mostly at home!), and the British deliberately chose not to accept the cost of building a fleet sufficient to secure both the home islands and the Empire.

In the 1930s airpower was seen as the solution ... but the Middle East, and lend-lease to Russia, absorbed the bulk of the air that might have been deployed to Malaya. (There's another fatal miscalculation here: the assumption that air could be deployed to Malaya fast enough to avert catastrophe -- but the time to do that would have been right after the Japanese occupation of French Indochina; by December 1941 it was too late to redeploy air fast enough to stop an invasion before it hit the beaches, even before the Japanese invasion of Thailand took out the intermediate airfields planes would need to get there from India. New air would have to come by ship, which it did, not fast enough.)

But we're getting away from the battleships, here. PoW and Repulse probably would have survived for a while with a carrier around to provide fighter cover. As it was, the Japanese committed two fast battleships/BCs (Haruna and Kongo) to the East Indies, and Force Z came pretty close to them during its northward run. An engagement between them would have been ... interesting. Has anyone ever speculated on the outcome of such a match?

I'm not so sure that was obvious in 1920-1925. Germany is under Versailles, France is a friend who neutralizes Italy, and Russia, the only non-signatory to the Washington Naval Treaty, is not likely to be mounting a challenge at sea any time soon. This only started to fall apart with the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, and it didn't become really critical until France got knocked out of the war and Italy joined in. Even before that, the British building plans had been increased to deal with the new threat. Vanguard was the only tangible result, but that's because battleships take a long time to build.

Again, sort of. The plan was never to fly in extra units after the attack started. That simply wasn't possible at the time. The planes might be able to deploy that way, but the ability to airlift the support echelons didn't exist until the 50s. And it's fairly obvious that the war in Europe was drawing off all the available air assets. The degree of muddled thinking is rather incredible, although there was also a systematic underestimation of Japanese capabilities, some justified, most of it not.

I'd say that Haruna and Kongo would be a good match for Repulse and PoW on a material basis. However, that wasn't Ozawa's entire force, and I expect that both ships would die to Long Lance as so many other allied warships did in that first year.

That could probably serve as an epitaph for Malaya in general.

“The next two waves attached Repulse with both torpedoes and level bombs”

Presumably the waves attacked Repulse

Yesterday I was reading about HMS Indomitable, and the question came to my mind: "If Indomitable hadn't run aground in the West Indies, and it had been part of Force Z, would she had made any difference?"

I asked my brother, the resident expert on the PTO, and he promptly answered: "No, she would have sunk with the rest. Her fighters were crap."

Do you concur?

Yeah, pretty much. I'd say that the bigger issue would be the generally poor state of radar at this point in the war, although British naval fighters weren't great either.

Emilio:

Crap against fighters, but against the bombers Japan sent they'd probably be highly effective.

I think they'd have been mostly Fulmars, which aren't great. Slightly faster than the G3Ms, but very marginal against G4Ms.

They don’t have to be very effective to spoil attack runs by unescorted torpedo bombers, though.

Tough call. HMS Indomitable's fighter complement really was woefully inadequate, both in quantity and quality (this really applies to all RN carriers prior to the arrival of significant Lend-Lease help). The 9 Sea Hurricanes weren't... necessarily... completely inadequate (assuming they were new-build airframes rather than hasty conversions of high-time RAF discards), but the 12 Fulmars were obsolete before they entered service, offering performance which was at best only marginally superior to the SBD Dauntless, and might not have been able to even engage the level bombers. Of course that might work out well for the RN (assuming the Fulmars didn't get suckered into attempting a long, fruitless tail chase), because the torpedo bombers were by far the greater threat. Slow and clumsy as they were, and lightly armed as they were, the FAA fighters probably could have done a number on unescorted G3Ms and G4Ms at low altitude (assuming the IJNAS didn't assign fighter escort to accompany the raids upon learning the RN had a CV in the area).

Even if Indomitable's fighters had been completely useless, of course, she'd still have been an additional heavy flak platform, and an extra capital ship target for the torpedo bombers. Maybe - maybe! - that could have been enough to get Prince of Wales and Repulse (as well as herself) back to a friendly port, albeit probably not unscathed.

Is there information on why this was the case? Did the IJN have the confidence in their maintenance capacity to fly no-weapons-expenditure sorties all the time, or was this a strike thrown against something else but retargeted on the fly, or something else?

It was definitely an anti-shipping strike, and I can't think there was another target available for it to have been retargeted from. At a guess (this was written 5 years ago, so memory his hazy) they were expecting to find Force Z before the planes arrived.

Did the first torpedo hit on Prince of Wales bend the outboard shaft all the way forwards to the engine room (in which case I'm surprised that the bending didn't cause the respective turbine to seize), or did the RN not bother sealing the shaft's bulkhead penetrations forward of the external shaft gland (in which case I'm surprised, to put it bluntly, that they'd be that stupid)?

I believe it was all the way forward to the engine room. I'm sure that the turbine was also messed up and the result slowed the whole assembly down, but the shaft has more angular momentum than the turbine, and the result is going to be a major mess before the combined drag on the shaft and turbine brings the whole assembly to a halt.

In that case, how on earth did the engine-room crew not notice that the shaft was bent where it came through the aft bulkhead of the engine room?! You'd think that, if nothing else, the sheer noise of a huge metal rod being forcibly bent would've attracted their attention...

I have no evidence that they didn't notice something going horribly wrong. But the damage was bad enough I'm pretty sure they just abandoned that space and didn't worry too much about exactly what. Later, with the ship sunk and Singapore in chaos, we presumably weren't sure of the exact details until they inspected the wrecks.

I seem to recall that part of the damage was caused by the local engineer trying to restart the engine after the torpedo hit, further trashing the watertight integrity... though what would have to be going on that they didn't notice how much damage had been done?

@Vikki wiki does mention that they improved the seals on the remaining KGs among a lot of other suitability improvements (some of which were apparently unrelated to the real cause of the loss due to uncertainty).

So it's possible they realized they skimped on that area.