From the earliest days of the Cold War, there was controversy over the the US Navy’s role in fighting the Soviets. Initially, the Air Force tried to cut them out entirely, but they managed to sell the carriers as nuclear strike platforms, retaining the mission into the 60s, when the ballistic missile submarine entered service.

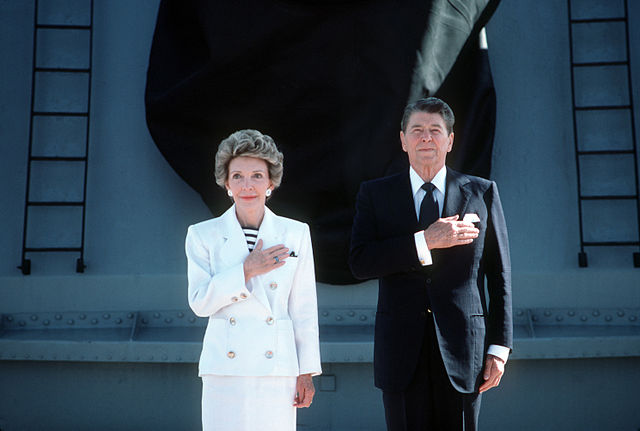

Iowa, reactivated in support of Reagan’s strategy, on an exercise

But in the 1970s, with the post-Vietnam drawdown, detente with the Soviets and the Carter Administration, Western leaders began to focus more and more on the Central Front in Germany. Sea power was seen only as important for ensuring the passage of convoys across the Atlantic in the face of Soviet submarines. The carrier force was allowed to run down, and shipbuilding concentrated on ships specialized in ASW. At the same time, the Soviet Navy, under Admiral Sergey Gorshkov, had begun to transform itself from the coastal-defense force it had been under Stalin to a true blue-water fleet, with the ability to hunt ships and submarines anywhere on the seas, a capability reinforced by larger and larger exercises. The Western navies, on the other hand, had scaled back their exercises, preferring to operate well away from Soviet waters.

Admiral Sergey Gorshkov

But in 1980, Ronald Reagan ran for president with a very different vision. Under the influence of a number of hawkish foreign policy experts, most notably Richard Allen, he saw a way to bring the Cold War to a peaceful end, a plan the US Navy would play a key part in. Instead of working solely to secure the transatlantic convoy routes, the navy would go on the offensive, threatening the flanks of any Soviet attack and pinning down forces in the Pacific and the Kola Peninsula that otherwise could be used in Germany. To support this, he proposed to build the Navy up from the approximately 450 ships it had fallen to a strength of 600 vessels. Supervising this was John Lehman, an international relations expert who had been deeply involved in developing the strategy at the Navy during the Carter years. Secretary of the Navy Lehman was also an A-6 Intruder bombardier with the Navy Reserve who would carry out his regular service in that role while in office.

John Lehman

Reagan and Lehman’s new plan would start with a bang. In the first August of the administration, exercise Ocean Venture 81 was launched. Instead of the normal exercise aimed at holding the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) gap against the Soviets, it instead involved sending two carrier groups into the Norwegian Sea, within striking distance of the bases of the Soviet ballistic missile submarines, one of the strategic centers of gravity in Soviet thought.1 By equipping a few ships with sophisticated electronic countermeasures, to allow them to emulate the communications of the main group, and by abandoning the WWII-era “bullseye” formation, the carriers were able to slip into the Norwegian Sea undetected. The first warning the Soviets had of their presence was when a flight of Bears were intercepted by Tomcats just outside Soviet territorial waters.

HMS Invincible during Ocean Venture 81

The Soviet reaction was predictable, as they surged their naval reconnaissance force to try to find the carriers. They eventually succeeded, but simulated air raids were repeatedly intercepted by Tomcats well before they reached launching position. The NATO carriers operated above the Arctic Circle, in waters they hadn’t reached since the late 50s, gaining experience in this hostile environment. And besides practicing strikes on the Soviet naval and air bases on the Kola Peninsula, they also worked with allied forces tasked with protecting northern Norway, greatly strengthening NATO’s flank.

An F-14 escorts a Soviet Bear during Ocean Safari 85

Nor were the effects of the new strategy limited to the Norwegian Sea. The Navy also abandoned a plan to swing the Pacific Fleet’s carriers to the Atlantic, and instead began exercising in the waters of the far northern Pacific. The fleet was expanded, most notably with the new Ticonderoga class cruisers, whose Aegis systems formed a useful backstop to the fighters tasked with shooting down the Soviet bombers, and the old Iowa class battleships, tasked with acting as backup capital ships and taking nuclear-armed Tomahawk cruise missiles into the Norwegian Sea.2 A PR campaign accompanied all of this, selling the Navy’s mission and utility to the American people and reaching its pinnacle with the blockbuster Top Gun.

Nimitz off the coast of Norway in 1986

Ocean Venture 81 was followed annually by similar exercises, each bigger and more sophisticated than the last, involving not just the USN, but also the Air Force and allied units. Besides testing operations in the Norwegian Sea, these also tried everything from operating in support of fighting in Germany and Denmark to striking targets in what is now Ukraine using carriers in the Mediterranean. There were also new tactical developments. In the 70s, some officers had noticed that it was possible to hide ships from radar detection near mountains, and the tactic worked well enough that the Navy was willing to sacrifice mobility for protection, taking the carriers into Vestfjorden, off the coast of Norway. An SSN would be sent in to sanitize it of submarines before the carriers arrived, and a line of CAPTOR mines would be used to seal the entrance, allowing surface ships and NATO submarines to pass in and out while keeping Soviet subs out. With the mines to protect against submarines, and the mountains making missile attack impossible, the carriers would be very safe, and the Soviets knew it.

Iowa and frigate Halyburton during Ocean Safari 85

The increasing pressure from the Maritime Strategy was met with panic among the Soviets. Their wargaming showed that their Northern Fleet was unlikely to last more than a week against the NATO force, and during the early 80s, they doubled down, building more new ships and submarines. But despite their best efforts, they were behind the Americans and falling further. Things came to a head in 1986, when Soviet military leaders requested their budget be tripled to allow them to counter the Americans. On top of all the sacrifices made for the Soviet military, this was too much. Mikhail Gorbachev, recently arrived in power, turned them down, and began to pull back. The large-scale Soviet open-ocean exercises ended, and he began a major campaign for naval arms control and restrictions on exercises, hoping to blunt the new threat diplomatically. The Reagan Administration wasn’t particularly interested in giving up its best weapons, and Gorbachev began liberalizing the Soviet Union in an attempt to rebuild the economy and gain the ability to counter the threat. Unfortunately for him, the Communist system was ultimately built on the threat of Soviet military power, most graphically demonstrated in 1956 and 1968. As Gorbachev became increasingly reluctant to use said power, first the Warsaw Pact and then the Soviet Union itself disintegrated.

Ronald Reagan aboard Iowa

The Reagan Administration’s masterful use of maritime strategy in the service of national goals played a key part in all of this. The USN peaked at 594 ships in 1987, within 1% of the 600-ship goal, and recent revelations from both sides show just how vital it was to the pressure that ultimately brought down Communism in Europe. The Soviets liked to use a map that showed them totally surrounded, by US allies in Europe and the Far East, and by American warships in the Norwegian Sea, Mediterranean, Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean, and Western Pacific. The threat of attack, nuclear or conventional, coming without warning and from platforms that were hard to find and well-defended, weighed heavily on them. In only a decade, Reagan, Bush, and their subordinates had turned a situation where the best most expected was a stalemate on unfavorable terms into a decisive victory, in no small part due to sea power.3

1 The Soviets expected a prolonged conventional war, with negotiations at the end based on surviving nuclear systems, so they put a high priority on protecting their own SSBNs and on destroying NATO systems. ⇑

2 This isn’t to say they couldn’t have been useful in ship-to-ship combat. During Northern Wedding 86, Iowa apparently snuck up on the blue force in a Norwegian fjord, getting within gun range before they realized she was there. ⇑

3 The main source for this post was John Lehman’s book Oceans Ventured. I’d encourage you to find a copy if you’re interested in more details of how this worked. Another good book is Norman Friedman’s The Fifty-Year War. ⇑

Comments

Very refreshing to see the reasoning behind the (end of the) Cold War presented as more than the mad brinkmanship and criminal irresponsibility commonly portrayed in popular culture.

@AlexT

I think it’s important to stress the “end of” in that statement. In part why things ended this way is that both sides had some time to feel each other out and develop a good understanding of what the other side actually might do. In the late 60s this was not well developed, the soviets in particular being extremely concerned that the US would launch a nuclear first strike. (As an American, this of course strikes me as preposterous, but then again that is the point: Both thought it pretty obvious they wouldn’t pull the trigger, when it wasn’t at all obvious from the other side.)

Also it’s worth pointing out we weren’t out of the woods in 81 either, Able Archer was still two years away.

I’m fascinated by the fact that the US and the USSR ended up essentially in war games with each other. My first instinct was that the Soviets shouldn’t have played along, since it was exactly what their adversary wanted. But on reflection the Cold War was far from a zero-sum conflict. There was a huge shared interest in avoiding a hot war, which was furthered by finding out how such a war would play out.

@Chuck According to what I’ve read on the subject, the US had an overwhelming strategic superiority over the Soviet Union up until the end of the 60s. They were absolutely going to nuke Russia in WW3 and would have won and the Soviets knew this very well. The fact that they managed to persuade the US public and government of the contrary is the most spectacular feat of disinformation I’ve ever heard of.

After the Soviets managed to amass a credible deterrent, I don’t think even a large-scale conventional war in Europe would have triggered MAD. Nobody was going to fight a total war over who controlled Germany or Poland. Or France, for that matter, thus the Force de Frappe.

This is perhaps a stupid question, but how much did being stuck in the fjords impede the operational utility of the carriers?

It obviously makes them harder to attack, which is good, and the Navy apparently thought this was worthwhile, but it seems like there are two major downsides: 1. Limited radar range for shipboard radars on escorts 2. (Possibly) limited ability to launch and recover aircraft due to geographic constraints. My understanding is that carriers generally need forward speed to augment the catapults for maximum launch capacity, and the fjords seem like they would limit the ability of the carriers to accelerate and decelerate in a reasonable amount of distance while also launching their air arm.

@Alex

Thank you. That was more or less what I was going for here.

@ADA

The other issue is that there are certain kinds of challenges you can’t afford to pass up, because they might be real. If NATO shows up in your backyard, then you have to respond.

@redRover

Vestfjorden is really big. Like 100 miles long, which is 3 hours even at top speed for a carrier. So it apparently wasn’t that much of a problem. As for escort radar, that’s what Hawkeyes are for.

@redRover -

1) That cuts both ways. If the target acquisition sensors aboard the incoming weapons don’t have time to see and guide on the ships in the interval between “emerging from the radar shadow of the mountain” and “whoops, I just passed it,” that’s pretty much a win. And of course the CV can put radar dishes up high enough to have a clear field of view after all.

2) It depends. In general the difference is that with less wind over the bow, aircraft might have to sacrifice fuel or payload to reduce gross weight. You might be able to make up the difference with tanker support, assuming you have tankers that aren’t already committed elsewhere. Or you might have to throw smaller strikes (using CV-based aircraft as buddy tankers), and/or shorter-ranged strikes, and/or carry fewer weapons on your strikes. But a lot of that would depend on the specific characteristics of the aircraft aboard, and exactly what you needed to do.

@bean: Halyburton, not Hallyburton.

Curses. I will fix that.

Speaking of Soviets, spambots are getting deployed like shtrafniki in Stalingrad, mass human waves to be slaughtered until victory or death.

Also, it’s interesting to think about how much the combination of leadership pairings meant to the Cold War ending as it did. That is, you needed Reagan in America and Gorbachev in the USSR to let things fall peacefully. Reagan vs say...Brezhnev, or even not-already dead Chernenko would not have ended peacefully, IMHO. Alternatively, Carter and Gorbachev would probably have come to some kind of arrangement and been okay-ish with each other. Reagan and Kruschev would have been quite the amusing combination.

That doesn’t jive with what I’ve read at all. In Schlosser’s Command and Control, he talks about how the US nuclear arsenal in 1949 was still in the single-digit warheads. This, at a time when the US had substantially demobilized after World War 2, and had not remobilized for Korea. If the Soviets had marched westward in ’48 or ’49, what, exactly, could the US have done to stop them?

@quanticle

Leaving aside what I think of Command and Control (Schlosser didn’t really find anything new, and his portrayal of a lot of what went on is not particularly accurate) both are true. In the late 40s, the US nuclear superiority was real, but only because the Soviets didn’t actually have any. The Soviet bomb test and Korea triggered a major buildup in the US arsenal, and from then until the late 60s, the US had a decisive lead. if the Cuban Missile Crisis had gone hot, the USSR would have been dead, and the US barely damaged.

@Blackshoe

Well, since I have the administrative controls, victory isn’t really on the table for them. If this lasts another few days, I may see if Said Achmiz has any other toys to fight them, though.

And interesting thought about leadership.

Sure, that’s absolutely true, but, at the same time, the US nuclear arsenal wasn’t large enough to actually stop a Soviet invasion. Like you said, that changes once the Soviets test their own nuclear weapons, but that’s not until later. My assertion is that there was a narrow window, corresponding roughly to the time around and just after the Berlin Airlift, where the Soviets had the upper hand against the United States in Europe.

Of course, it was a very narrow window, and a very narrow edge, and the uncertainties were wide enough that Soviets didn’t actually invade. But maybe, just maybe, they could have.

@bean

the US wouldn’t have been damaged in 1963, but europe wouldn’t be in great shape. the soviets had plenty of IRBMs and smaller, IIRC.

@quanticle

In general, you’re probably not wrong, although I’d be somewhat skeptical of Soviet capabilities in that timeframe. I remember reading (but can’t source offhand) that the Soviets cut back a lot more post-WWII than anyone in the west realized, and might not have been able to go west nearly as easily as we thought. Particularly given how badly they got hammered by the Germans.

@cassander

True, and I thought about getting into that, but decided not to.

There’s also the fact that Soviet logistics in The Great Patriotic War relied so much on stuff that was Made in America to the point at which it’s somewhat doubtful if they could’ve sustained a serious offensive without Lend-Lease.

We will probably never know the truth about Soviet capabilities in the immediate post-WW2 period. But in hindsight, we know now that between purges, deliberately engineered famines, and a couple of years of brutal German invasion and occupation, Soviet population was down by a LOT - by the end of the war, the Red Army’s manpower situation was scarcely better than Germany’s. And we know that Lend-Lease wasn’t just tanks and planes, or even tanks, planes, trucks, and railway stock - it was also millions of tons of things like food, textiles for uniforms, high-octane gasoline, and raw metals and chemicals, which all told freed up at least a couple of million extra warm bodies for military service. We also know (and should have known at the time) that the Soviets had a whole lot of rebuilding to do back inside their own borders, which was necessarily manpower-intensive. And finally we now know that most of Eastern Europe was NOT happy about trading Nazi oppressors for Soviet oppressors, so the Soviets had to maintain occupying forces to support their newly-installed puppet governments - which may be where Western observers saw “vast Soviet hordes” across the borders, not realizing that the West wasn’t really those formations’ target.

Maybe the USSR could have launched an offensive into Western Europe ca. 1948-49, despite the many demands on their depleted resources. Maybe they could. But it might be relevant that in Korea in 1950, the Soviets were content to sit back and let the Koreans and Chinese do almost all of the dying.

The West was perfectly aware of it at the time. However the British and the French were in no position to do anything about it, and the US didn’t really care. Understandably so, but it wasn’t a matter of ignorance.

@philistine

It’s also indicative that pretty much as soon as stalin kicks the bucket his successors moved to end even the korean conflict, which had to be a serious drain on soviet material resources.

@AlexT

That level of deception was quite a feat, in some ways as impressive as actually building the things. The soviets had leaned quite a bit about opsec and deception fighting the Nazis, and gained a fair amount of relevant experience in cloak and dagger work by murdering each other in the various purges. (I just found out they have a word that encompasses military deception, maskirovka)

I could have sworn I learned about maskirovka from Tom Clancy, but if not, from that genre of novels

While digging into the evolution of Soviet military doctrine, I recall reading some persuasive arguments that “Maskirovka” is a bit like “Blitzkrieg,” an external, foreign framework imposed on elements of another nation’s practices that wouldn’t be used, or perhaps even recognized, by the actual people responsible for formulating and employing those practices. It is a Russian tendency to consider the use of deception at all levels of conflict, it is not some sort of unified doctrinal concept and associated standard practices with a neat name. At least so I read.

And comments on this one are closed because of spam. If you want to talk about it, drop a note in the OT, and I can open it up.