In the years before WWII, there had been serious discussion of the use of flying boats as long-range bombers. Unfortunately, the late 30s saw land-based aircraft improve to the point that waterborne planes couldn't hope to keep up, and their strategic operations during the war were limited to one strike against Pearl Harbor. And after the war, the flying boat was gone for good. But it almost wasn't that way.

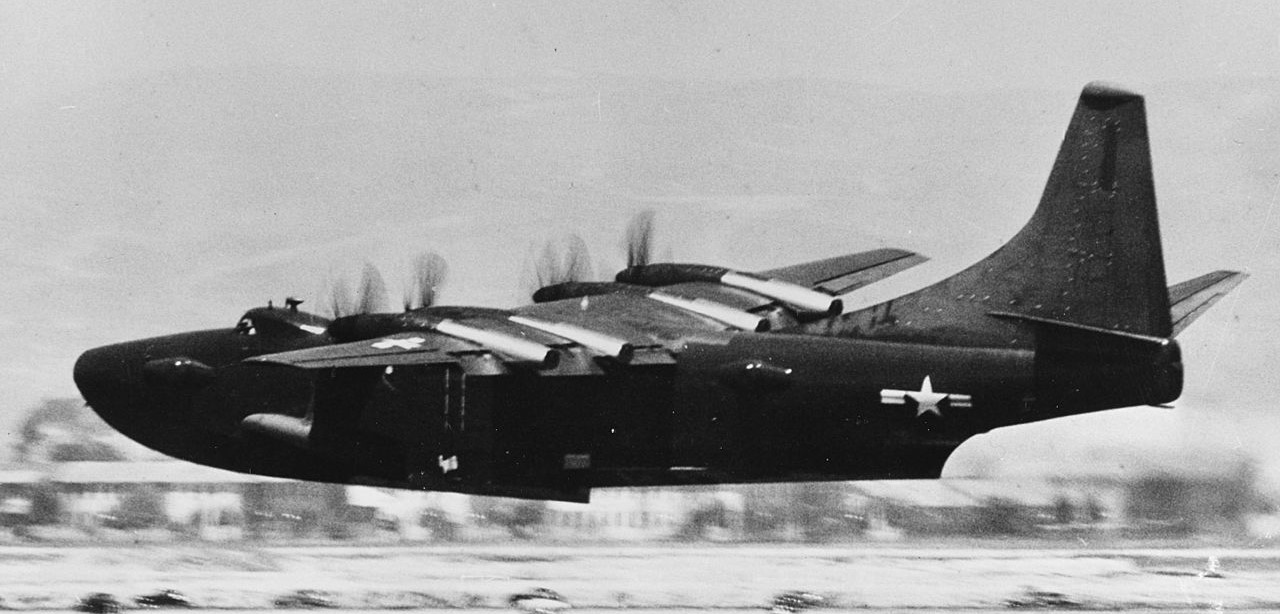

The P5Y, the first of the new seaplanes

The first factor was the work of aerodynamicists in the late 30s and early 40s. Flying boats had always been hindered by the need for reasonable waterborne performance, and by the late 30s, the demands of taking off and landing imposed an intolerable cost on their airborne performance. But several teams in both the US and Germany challenged this accepted wisdom, discovering new hull forms that allowed flying boats to be much longer relative to the width of their hulls, narrowing the performance gap with their land-based counterparts. By the late 40s, Convair had several designs that should work quite nicely, and was under contract by the Navy for a new patrol plane, the P5Y, which could fulfill these promises.

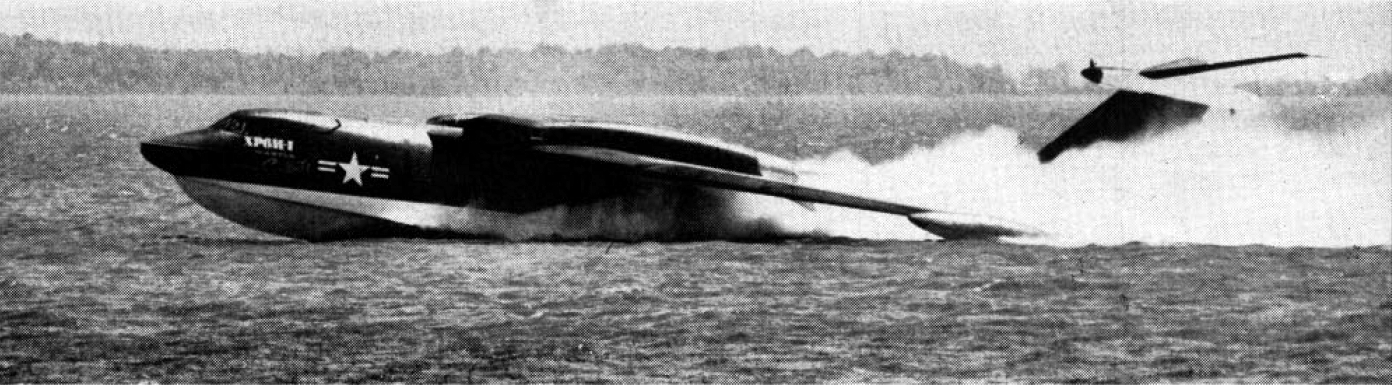

The F2Y Sea Dart, another advanced seaplane

The second factor was politics. In the immediate postwar years, the Truman administration was deeply concerned with cutting the defense budget, putting a major squeeze on all the services. The only mission that could secure adequate funding was nuclear strike, and the Navy's attempt to get a piece of the action for its carrier force wasn't going well. But some officers saw the new seaplanes as a potential alternative. They could be much bigger than even the biggest carrier planes, giving improved range, and they were able to operate from any reasonably sheltered stretch of water. This also allowed the force to disperse, making it much harder to wipe out. And by replacing carriers with tenders and refueling submarines, the whole force would be much cheaper. The proposed Seaplane Striking Force (SSF) also had the important secondary role of minelaying in support of the USN's anti-submarine campaign.

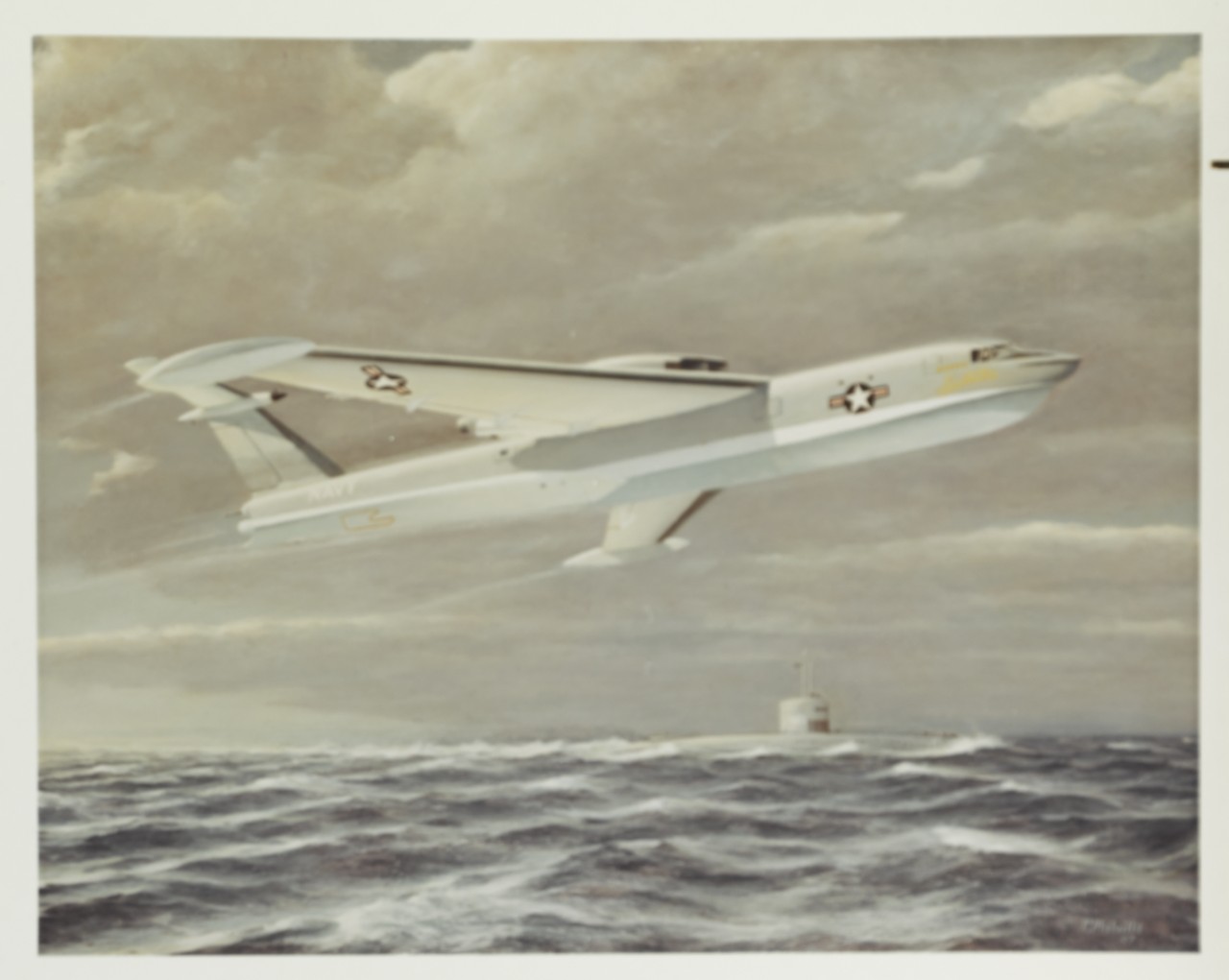

The XP6M prototype taking off

As a result of all of this, the USN issued study contracts to Convair and Martin for a new strategic seaplane, designed to attack at extremely low level with either mines or nuclear weapons. Ultimately, the Martin design was selected in late 1952 as the P6M Seamaster, capable of carrying 30,000 lbs of mines in a rotating bomb bay, pneumatically sealed against sea water and loaded using an overhead rail system while the aircraft was afloat. To keep them from ingesting water, the engines were mounted on top of the wing, and an advanced electronic bombing/navigation system would allow it to hit targets accurately at night and in bad weather. Combat radius was around 750 nm, and it could make 585 kts on the deck, a rather impressive figure. On the whole, it was a reasonable competitor to the B-47 that would soon enter service as the Air Force's primary nuclear bomber.

An F2Y at high speed

The Navy gave a high priority to the SSF, with the P6M getting an order for preproduction aircraft before the two prototypes even flew. Nor was the P6M the only airplane involved in the program. The first P5Y prototype was destroyed by an engine failure in 1953, and the Navy decided to scrap it as a patrol aircraft, instead procuring a cargo version, the R3Y, to support other seaplane operations and even serve as an airborne landing craft. Protecting the force would be the job of another Convair product, the F2Y Sea Dart fighter. The Sea Dart, instead of using a conventional flying boat hull, took off using what was essentially a water ski, reducing the impact of the aquatic runway on the aircraft. It was designed to be supersonic, and protect not only the SSF, but also amphibious operations, allowing the carriers to retain their mobility instead of being tethered to the beachhead.

The R3Y unloads a tractor

None of the aircraft had a smooth development program. The R3Y struggled with engine problems throughout its life, which would eventually lead to its cancellation. The F2Y suffered from the inability of its engines to deliver their promised thrust, a problem that plagued many contemporary aircraft programs, which, combined with a lack of area-ruling, left it unable to break the sound barrier. Severe vibration from the hydroski was another problem, but both issues were at least partially addressed in the preproduction aircraft, which first flew in 1954. One of these went supersonic in a shallow dive, the only seaplane ever to do so, but disintegrated two months later due to vibration problems, killing the pilot. Shortly thereafter, the Navy pulled the plug.1

An early Seamaster

The P6M did somewhat better, the first prototype flying in mid-1955, although it was destroyed only five months later when some form of control problem threw it into a 9-G loop, causing it to break up in midair and killing the crew. This was not uncommon at the time, and the Navy continued to work on the second prototype and the six preproduction aircraft despite not being able to pinpoint the cause of the accident. Unfortunately, a similar problem hit the second prototype 11 months later, although the crew were able to safely eject. During the investigation, they realized that a calculation error had left the actuator for the elevator too weak, and allowed the aerodynamic loads to overpower it. With the problem fixed, work on the preproduction aircraft, designated YP6M-1s, could continue.

Albermarle shows her ramp

But the SSF wasn't just airplanes, and work was also being done on the ships to support it, mostly converted from the WWII-surplus vessels that the Navy had in great numbers. Large tenders would be needed to bring the Seamasters out of the water for servicing, and conversion of the first, Albermarle, began in 1956. The biggest change was the stern ramp, which could be extended 100' aft of the ship to haul one of the 40-ton flying boats out of the water and onto the tender's stern. Besides the workshops and support equipment required for the new, sophisticated aircraft, Albermarle also had facilities for storing and handling nuclear weapons. It was soon joined by a second former seaplane carrier, as well as a pair of LSDs, which simply brought the flying boats into their well decks for servicing instead of relying on a ramp. The ultimate tender was to be converted from a WWII escort carrier, but it was never built. Smaller tenders, intended for operations in forward areas, were also planned, but never constructed. The submarine portion of the system was actually tested, with USS Guavina converted with tanks for 160,000 gallons of fuel and a platform for refueling.2

The first YP6M-1 flew in early 1958, but that was almost the last piece of good news for the program. Vibration problems continued, and new problems popped up with water ingestion and spray. The advanced avionics system, intended to take care of navigation and weapons delivery, was unreliable, ineffective and massively over budget. Costs were rapidly becoming an issue for the airframe as well, and the schedule began to slip. To make matters worse, the Navy as a whole was experiencing a major budget crunch, driven largely by the costs of the Polaris program, which also offered a serious competitor in the nuclear deterrent role. By mid-1958, unrest with the program was growing in Washington, and that November saw the planned buy limited to only 8 follow-on P6M-2s for development of seaplane tactics. Proponents of the program began to emphasize its multi-mission capabilities, with plans not only for nuclear attack and minelaying, but also photoreconnissance and in-flight refueling, both accomplished with specialized equipment in the bomb bay. There were even plans to use the Seamaster as a missile carrier, with a Regulus II, too big for the bay, mounted on top of the airplane, although this plan didn't survive long.

The P6M-2 took to the air in February 1959, and immediately ran into problems. Engines stalled and high-speed control and vibration problems continued to plague the Seamaster despite Martin's efforts. Making matters worse was Martin's attitude towards the problems, including in several cases arguing that issues were minor and didn't need to be fixed. The axe finally fell in August, when the decision was made to cancel the program. All of the airplanes were grounded, and Martin was finished in the manned aircraft business. The Navy would instead rely on its carriers and submarines for nuclear strike. A year later, all of the P6Ms would be scrapped, a sad fate for such an interesting aircraft.

So what to make of all of this? The SSF was an interesting concept, a very different way of operating and delivering nuclear firepower from the models embraced by either the Air Force's Strategic Air Command, the Navy's carrier force, or the missiles that would come to dominate the role in the 1960s. But it was the victim of problems technical, programmatic and financial. On the technical side, while the ability to build a seaplane with such high performance is astonishing, solving these problems took more time and money than the Navy had. This was compounded by failures of program management. Martin attempted to sell a project they couldn't really deliver, while the Navy didn't provide sufficient oversight. In practice, it probably should have been cancelled before the contract for the P6M-2 was issued. And all this took place against a background where every part of the Navy's budget was being cut to support the creation of the Fleet Ballistic Missile force, which would ultimately emerge as the Navy's nuclear arm.

1 Other planes were investigated as part of the SSF, including an ASW seaplane that was designed to routinely land on the water in the middle of the ocean to employ a dunking sonar, similar to that used by helicopters. One proposal gained low-speed performance by pivoting its wing 30° upward, but the P6Y actually selected just used boundary layer control instead. Of course, the whole thing was soon shelved. ⇑

2 Some plans were drawn up for a nuclear submarine seaplane tender, for a proposed nuclear-powered seaplane. The tender would carry chemical fuel (necessary for dash performance), extra weapons and replacement crews, required because of radiation exposure on the lightly-shielded seaplane. ⇑

Comments

As great an article as I've read in a while on here. Reminded me of the WWII After WWII site with their long form pieces and great photos. Thanks.

Taking off in one of these beasts must have been terrifying.

I wonder if it all would have worked in a different Navy.

Say... the French, who didn't have a lot of normal aircraft carriers as a backup plan while still having a scattering of territories world wide that it wanted to be able to send potent aircraft to.

Now the French didn't have the required technical resources at the time, but they did a decade or two later.

Wow, the P6M is a beautiful bird. It's even more impressive when you consider what the average seaplane looks like.

Wow, and the last US seaplane operation involved naval gunfire support... from the Coast Guard.

Vietnam had so many weird situations that apparently nobody wanted to remember or learn from.

@Doctorpat: British military seaplane projects existed, but they didn't last as long as the US ones. The Saunders-Roe SR.A/1 jet-powered flying boat fighter was cancelled in 1950. I don't think there was every any thought of using seaplanes as strike aircraft, though Saunders-Roe did propose military uses (reconnaissance and transport) both for their turboprop-powered Princess commercial flying boat and the unbuilt jet-powered Duchess and Queen designs.

I can imagine proposals for some kind of nuclear deterrent involving launching Blue Steel or Skybolt from a military version of the colossal, 24-engined Queen- though I can't imagine it getting much further than the ideas for a nuclear missile-carrying VC-10...

Whoa, this is like looking into a parallel universe...

I wonder about the viability of the SSF if it had been developed as a complement to the carrier force instead of a competitor? That is, you'd put both carriers and seaplane tenders in your ~~carrier~~ aviation task forces and then decide for each aircraft role whether it would be better served by a seaplane or a carrier plane. So you'd probably skip the F2Y and its skis (which seem like a great idea as long as there are no waves) and also spare yourself the challenge of designing carrier-based heavy attack planes.

@Doctorpat

The basic problem is that by 1950, big airstrips were common almost anywhere you'd want to deploy aircraft, and for the exceptions, building an airstrip for your existing planes is a lot cheaper than designing and procuring a bunch of high-performance seaplanes. Only the US was likely to need the sort of expeditionary capability that seaplanes provided.

@AlphaGamma

The 24-engine ballistic missile flying boat is second only to the ICBM dirigible as far as silly nuclear delivery concepts go.

@ADA

I'm not sure that would have worked. A couple of issues spring to mind. First, they might not be entirely operationally compatible. Seaplanes are essentially like landplanes that have a base on ships. You can't operate them while doing 30 kts, and probably don't have the capacity to tow them all around, to say nothing of operating them in the open ocean during bad weather. Second, cost. Heavy attack airplanes are to a first approximation self-contained. You only have to pay for the planes, instead of paying for planes and new ships. Third, politics. The carrier aviation community isn't going to want to share their toys, and having the heavy attack mission gives them a reason to ask for bigger carriers.

@bean Ah, I hadn't realized the extent of the operational issues. That does change the equation.

Searching a bit on the topic, I found this argument for a modern revival: https://warontherocks.com/2020/07/bring-back-the-seaplane

One section does contemplate a full SSF comeback, with some tacit acknowledgement it's quite a stretch. But mostly the article focuses on logistics, particularly tankers. Their arguments for why this would be useful seem fairly solid, but I guess the hard question is whether it's useful enough to justify developing an entire area of technology.

The political side would probably still be a nightmare, but an astute seaplane champion could maybe sell it as letting both land- and carrier-based aircraft focus more on the pointy end of things.

I wanted to hear more about the ICBM dirigible, because silly nuclear delivery concepts are my jam, and I found this PDF summarizing a long list of possible nuclear delivery systems that the DoD studied. I didn't see a 24-engine flying boat on the list, but it does include dirigibles, seaplanes, trains, hovercraft, silos filled with sand, and putting missiles in floating pods to let them drift randomly around the ocean (an idea which they note "poses safety problems of an unprecedented kind.")

@beleester: Interesting, I hadn't seen that!

More recently, there was the British Trident Alternatives Review (PDF), which dismisses them with the line

@ADifferentAnonymous

Would it be possible to turn some of the littoral combat ships into seaplane tenders, I wonder? They're admittedly rather small, but the ability to work in close to shore and their high speed might both be useful.

@Goose of Doom: Probably "doable", but not as useful as turning, say, the EPF into a seaplane tender. They'd have more cargo space to turn into shops, although I suspect weight issues are a major, major factor against both hulls.

If we're really embarking on the crusade for T-AV-X to support our notional fleet of nuclear-armed seaplanes, whatever CHAMP ends up being is probably our best bet.

As an aside, interesting to note that both Japan and Russia still operate seaplanes.

I sort of wonder why we don't see special forces (at least in the U.S. and as far as I know in the rest of NATO/the EU) use seaplanes/floatplanes in limited numbers, sort of like how they use STOL aircraft such as the C-212. Not only does it seem like a seaplane would be useful for landing at sea, but there are also enough large-ish lakes in various parts of the world that using them in places where you cannot access a runway might be viable in a pinch.

I assume the answer to this is just that helicopters and the V-22 get you almost everywhere you could possibly want with regards to landing options, and you can always rappel/paradrop into places where you can't land. But still, it would be pretty cool to see a few PBY-type aircraft ferrying commandos around.

I am very far from sure that there aren't any of those kind of planes, and quite sure that if they found themselves needing one with a bit of lead time, they'd acquire one. SOCCOM has all sorts of weird toys stashed away, although this might be a case where a CV-22 with aerial refueling is just better in pretty much all cases. But they'd be using something off the shelf, not a bespoke design.

It is interesting to me how old nuclear documents are always littered with tidbits that are strangely terrifying. Reading the PDF @beleester linked, I found this:

Markdown pls.

I need to find somewhere to preview comments before I post.

Possibly a combination of "barges are very vulnerable", "everything worth blowing up in the US is on a waterway anyway", and "wait wouldn't the navy take this over? let's rubbish it even harder!"

I do love the idea of a brown-water nuclear strike force through...

What % of the navigable US inland waterways have large dams on them? That's one way to take out a long river using a single nuke.

I'm not sure it would be fast enough. That's going to take tens of minutes to hours, minimum, which is plenty of time to fire a missile back.

Preach it, brother! I have about an 80% expectation that this post will come out screwed up in some way. I don't know why I can't understand Markdown, but I've never successfully used it in a post here.

All of them. All of our useful navigable waterways have some sort of control structures, since God isn't gracious enough to give us something that works well out of the box. IIRC, the longest stretch would be the Mississippi from the Head of Passes up to Chain of Rocks in St. Louis, which admittedly is a long way, but even below Chain of Rocks there's significant channel maintenance.

I've not studied the effects of a nuclear explosion on a dam, but it actually wouldn't surprise me to find out it's not as bad as you'd think. 100 psi isn't actually a whole lot compared to the instantaneous pressures developed in an earthquake. It's over them, sure, but only by about 5x or so, which may or may not be enough to cause a gross collapse, compared to a non-collapse condition that we'd only find dangerous enough to refuse to endanger people to fix in a peacetime environment. I think that an individual strike is only putting a navigation dam out of service for months, not years.

The real problem is that a major countervalue strike screws things up so badly across the entire US that there's just not enough resources to fix stuff that's going to kill people next winter, much less a dam that's only useful to a non-wrecked economy. I'd suspect that's the source of a marginal increase in effort by the USSR being able to reduce navigation, rather than these being huge effects on their own. The breaches in the Moehne and Edersee dams caused by Operation Chastise were fixed in some six months, IIRC, and that's the sort of thing you can recover from if you haven't suffered a complete economic collapse.

Dams may be hard targets, but they're definitely not harder than missile silos. You'd go after them with surface bursts, either on the dam itself or the reservoir behind them. Either way, if the bad guy wants the dam taken out, the dam will be taken out.

You're forgetting the intracoastal waterway, which is 3000 miles and pretty much flat. I think there are a handful of locks. However, I'm a lot of it falls under what echo was saying about already being targeted for other reasons.

On the markdown front, I've found Markdown Live Preview, let's see how well it works.

Huh, wwiiafterwwii just had a blog post talking about some related aspects right after this went live.

From @Blackshoe's link:

"The crew level of the ship was drastically reduced from WWII. As USS Albemarle the US Navy manning was 100 officers and 1,035 enlisted sailors. Now as USNS Corpus Christi Bay, the ship had a MSTS/MSC captain, 128 civilian sailors, and a maximum of 361 US Army soldiers."

Wow

I'm suspicious of the complement numbers. Albermarle and Curtis, as well as Currituck and Norton Sound all have complements around 1100, but the last two units of the Currituck class are listed under 700. I can't find any changes in the design that would justify this, which leads me to suspect that as usual we're dealing with idosyncratic math. The initial figure probably includes most or all of the supported seaplane unit, a conclusion supported by the unusually high officer-to-enlisted ratio. 100 officers is almost as many as Iowa's design complement, and she had 80% more enlisted men to go with them. As Corpus Christi Bay wasn't operating helicopters, the manning numbers could be a lot lower.

(But all of this is reminding me that I really do need to look into seaplanes in WWII more.)

I understand the times, and the wasteful of potential way they order things. They produce one model, and when it didn't work out, that's it for the entire concept.

With the enthusiasm for solving everything by threatening nuclear strike, they had no use for multi-mission capability. As the one general said, with the Air Force's ICBMs, we don't need a navy or marine corps.

Weather is always brought up as an objection to seaplanes, and always overstated. They're fine for most of the ocean, most of the time. If one spot has too much weather (which stops all other air travel, small watercraft, and larger watercraft have to stop most secondary operations and hold course), another spot just over the horizon will be calm. Beriev and ShinMaywa large seaplanes today demonstrate operations in rough water (4 meter waves and 30+kt wind. Never a crosswind, any wind there is, a headwind.)

The multi-mission capabilities of a seaplane force can't be missed today, or in any other situation than during the debate between the lucrative options of supercarriers or ICBMs and Bombers. Reportedly, by the end of this year (early 2022), SOCOM will be testing the old idea of putting the C-130 on floats.

See the recent article by the USN Institute: "Modern Sea Monsters" about ram-wing GEV/Ekranoplans. Many designs of which (and working examples of the type around the world) can actually fly shorter distances or lighter loads. There were many competing designs for seaplane fighters and attack planes besides the Convair. Both Boeing nd Lockheed evolved the concept. The USSR tried out the Be-10 as a training squadron. when it ran into development problems, the US was also cutting its interest in such things, so they dropped it, though they kept seaplanes in the Navy. The Russians had several designs for subsonic and supersonic-dash strike seaplanes. See the Myassishev M-70, Bartini A-57, others. These things would have been terrifying, and if both sides had built such things, you'd never know where a strike could be staging from or where to catch the planes. They only help the attacker and make the defender's job harder. Like orbital interceptors and guided orbital bombardment (Project Thor), these things were all too dangerous. Too "destabilizing", too decisive, which isn't wanted for ongoing lucrative brush wars. We're only just now getting into hypersonic suborbital missiles, and we still don't have global semi-ballistic package freight (which could be indistinguishable from hypersonic impactors or anti-satellite weapons)

The extremely un-aerodynamic boat-shaped fuselage and the step under the hull isn't necessary. See the Chase/Stroukoff YC-134e. Upgraded C-123, with BLC for STOL and waterborne fuselage (minus a step or other boat hull parts) with a pair of "pantobase" skis under it. On the skis it operated from pavement, unimproved ground, sand/swamp,water,ice/snow.

John Frazer:

Somewhat, those who say that airships should be used instead certainly do, or they just forget that airships are even worse at bad weather.

But if you don't have a lagoon nearby and have widespread bad weather to the point at which you can't just go a little bit over the horizon…

John Frazer:

Shinmaywa claim 3 m but say that their seaplanes have handled more, the current large Beriev designs claim a bit over a metre (their hulls aren't as deep as that of the US-2).

John Frazer:

Only three of which ever flew and only the Be-10 entered service.

John Frazer:

How is this any different from an aircraft carrier or even land based aviation?

John Frazer:

Or just too expensive to be worth the development given the limited extra capabilities they could provide.

What can a seaplane do that can't be done by carrier borne or land based aircraft? I can think of long range SAR but everything else can be done just fine by CTOL, CATOBAR or even STOVL aircraft which are available off the shelf.

If you can't afford at least a STOVL carrier you've got no business even trying power projection beyond the reach of land based aircraft.

The reason that orbital bombardment was never a thing is that when you're on a planet and the person you want to attack is also on that planet, it's generally a lot easier to launch the thing you want to attack them with when you want to attack them than it is to launch it ahead of time. For one thing, you always know how far away from the target you are, and how long it will take for the weapon to get there. Orbital weapons don't have that advantage, and the vast majority will be in the wrong place at any given time. Some math I did years ago suggests that for a 30-minute response time (so no faster than an ICBM) and global coverage with current-ish rocket technology, you're going to need something like 70 warheads. Only one will be able to hit within 30 minutes, followed by more at intervals of about 8 minutes, maybe with some gaps or clumps as the orbital planes move. Worst-case, the last might not arrive for up to 12 hours after the first, although that depends on the exact location and orbital geometry. You can cut down the required number with various clever tricks if you have a restricted coverage area, but cutting response time more is going to mean much bigger rockets and drive up cost significantly. In any case, it's not going to work out all that well.

(As an aside, I'm pretty sure that Project Thor was never an official name. No records of it in DTIC, and it's easy enough to see the issues with a few hours of math.)

How much of the 30min is orbit to ground, and how much waiting for the right time zone to come up? (I imagine the answer boils down to what is your d-v budget)

The big advantage of orbital weapons was supposed to be evasion of enemy early warning systems. If you had a Soviet Union-shaped constellation and were willing to wait for the stars align to launch your ambush, how good could you get the warning numbers?

The big cost here is that the groundtrack spacing is based on a divert burn a quarter-orbit from the target, which is going to mean about 22 minutes to reach it afterwards. (Yes, there are several simplifying assumptions here, and it could be lower if the target was closer to the orbit track.) Number in each orbit is required to keep total time down to 30 minutes.

That's going to make your warning numbers a lot worse, because orbits are very predictable. If they see that sort of situation occurring, they'll be on high alert. On the object level, don't remember off the top of my head. Be a bit surprised if you could make it less than 10 mins or so from deorbit to impact, at least for reasonable systems.

10min (if you get warning at all) doesn't sound like enough time to evacuate your king (or local equivalent). No wonder everyone was so worried about surviving a decapitation strike in the 60's & 70's. Your enemy buying ONE of those and hiding it from you is somewhat realistic.

The Soviets had FOBS but orbit requires more Δv than the sub-orbital ballistic trajectories used so a rocket that would normally carry either one big bomb or lots of small ones could only carry a single small one.

This wouldn't work as well for a reaction strike where the opponent is already on alert and in hiding, but for a strike out of the blue it seems feasible? Like, if you line up the orbits so that you have four bombs in one track close together, and they just sit there for a year, they're not going to evacuate the capital once every day or three as the orbits pass overhead.

@redRover

Fair point, although avoiding that is why the Outer Space Treaty bans stationing WMDs in space. And 10 minutes is plenty of time to order a retaliatory strike.

In the 60's, are you sure? I feel "Hey boss, come take a look at this funny RADAR track." would five at a minimum. Then you need at least 2 trips through switchboards/secretaries. (warning to HQ, orders out of HQ) To say nothing of time spent convincing anyone.