When US designers finished the North Carolina class, their first since battleship construction resumed, they weren't entirely happy with the result. It was a ship armored against 14" guns in a world where the escalator clause had just come into force, allowing future battleships to be built with 16" weapons. And while it would seem that the treaty limit of 35,000 tons would preclude substantial improvements over the North Carolina, the preliminary design team, lead by Captain A. J. Chantry, produced a class that was by far the best of the treaty battleships and arguably superior to any battleship ever built outside the US.

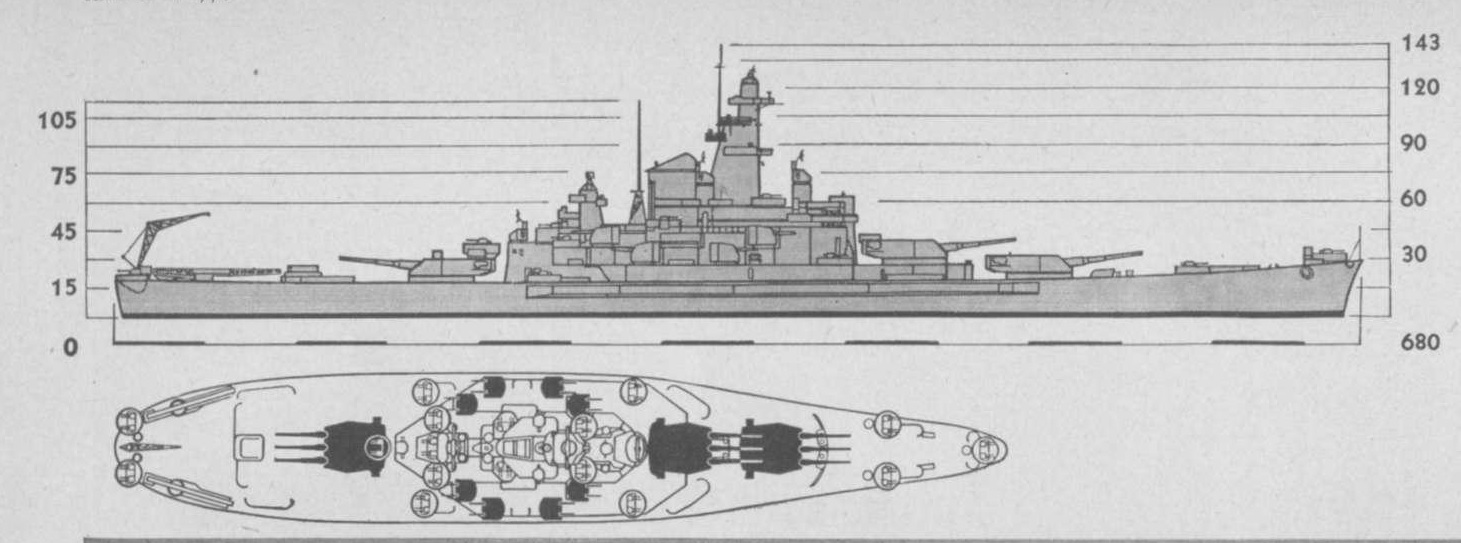

Massachusetts of the South Dakota class in 1944

When design work on what became the South Dakotas began, it looked like they would revert to the traditional American type, slow and heavily-armored. The initial requirement was for a speed of only 23 kts, based on the estimated speed of the Japanese battle line. However, in late 1936, US intelligence became aware that the reconstructed battleship Nagato had made 26 kts on trials, and a speed of 27 kts swiftly became the standard going forward.

Even before that decision was made, the design was obviously not going to be straightforward. The immune zone was to be 21,000-30,000 yards against the 16"/45 gun, which would mean a 5.9" deck and 15.5" belt. The deck was not a big problem, but the belt was too heavy. The obvious answer was to slope the belt, increasing its effectiveness. This raised other problems. The ships were limited by the need to fit through the Panama Canal, which restricted maximum beam to only 108'. If the belt sloped inboard at 19°, the waterline would be dangerously narrow, compromising stability. Worse, as the ship got wider higher up, it would add topweight, exacerbating the stability issues. The solution was to move the belt inside the hull, which restored stability in undamaged condition. Damaged stability was still a concern,1 but Chantry came up with a solution to bring the belt closer to the hull. The upper section was sloped outward at around 45°, opposite the lower section of the belt. This would make it less effective at long range, but better at short range, and would reduce the total area of deck that needed to be armored. However, it would ultimately be abandoned when it was discovered to actually cost several hundred tons more than a simple inboard-sloping belt would have.

South Dakota shortly after her completion. The characteristic slot along the side is clearly visible.2

The angled belt also helped solve the problem of underwater shell hits that had become apparent so late in North Carolina's development. A thin lower belt was extended down to the bottom of the ship, forming one bulkhead of the torpedo defense system, although, unknown to the designers, this seriously compromised its effectiveness against underwater explosions. A 60 lb (1.5") STS belt had to be added at the waterline, to prevent splinters and light damage from causing flooding and destroying stability. This cost a substantial fraction of the weight saved by the internal belt. In the end, however, Chantry and his team had produced a very good protective scheme, one that was good enough to be essentially copied for the follow-on Iowa class.

Indiana

Despite their efforts, though, the scheme was considerably heavier per foot than that of the North Carolina, which meant that the ship itself would have to be shorter and more cramped. If armament was to be held constant, the shorter citadel would mean less length for the engines. Worse, a shorter ship is harder to drive through the water, so the loss of speed would be considerable. This seemed to pose an insoluble problem in light of the increased speed requirements, although if a North Carolina plant could be shrunk down from 176' to around 132', it might let the ship make 26 kts. Initially, the plan was to position the boilers over the turbines, much as had originally been planned for the Lexington class battlecruisers. This would have meant having the armored deck jog up over the machinery spaces, a far from ideal solution. Thanks to developments in high-temperature high-pressure steam systems, the final solution was to place a single boiler in each of the four engine rooms, next to the turbine set. In the end, the Bureau of Engineering was able to cram in 135,000 SHP in 16' less length than had been required for the 115,000 SHP for the North Carolina, keeping speed about the same, and with only a 9% increase in weight.

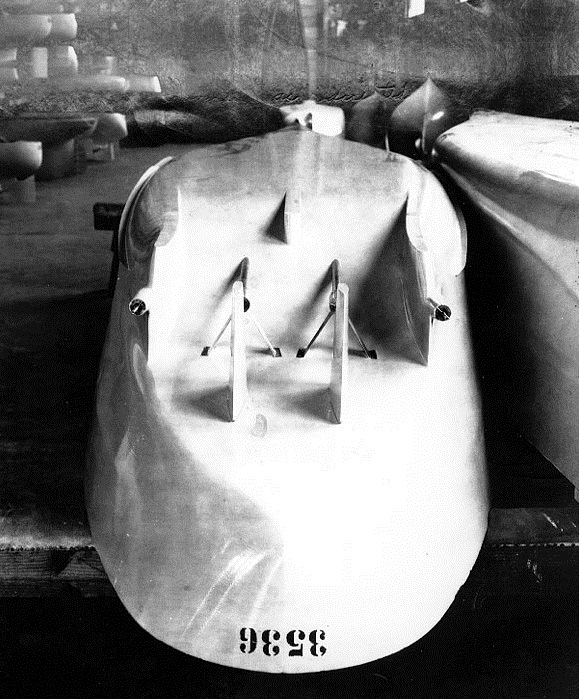

The unusual shape of the aft hull can be clearly seen on this towing tank model

Trying to build such a short ship caused other problems. To keep the magazines safe, the turrets had to be located where the hull was wide enough to provide sufficient depth for the TDS. Turrets 1 and 2 couldn't be pushed too far forward, which cramped the superstructure badly, and ultimately resulted in the turret arcs being restricted to only 290° instead of 300° and the bridge being much smaller than usual. Aft, the hull needed to narrow for hydrodynamic efficiency, but the TDS for Turret 3's magazine worked against this. The designers realized that the important factor was not the beam, but the hull's cross-section. They cut a tunnel out of the bottom of the hull, with the inboard shafts running through it and the outboard shafts being protected by a pair of skegs, which also served to defend the opposite shafts from torpedo hits. This was an even more exotic design than the one on North Carolina which had given so much trouble, but it worked well. There were some problems with vibration, and the propellers were altered a couple of times, but they suffered much less than their predecessors.

Massachusetts from above, showing the short hull of the class

Even after the design was mostly finalized, more detail changes had to be made to save weight. Crew spaces were shrunk, including smaller staterooms for officers.3 A 400-ton overweight was dealt with by changing definitions. The Washington Treaty defined standard tonnage to include all equipment "intended to be carried in war". The design already included significant paper savings, notably carrying only 75 rounds per main gun, although there was room for a "mobilization allowance" of another 55 that was not included in the treaty tonnage, saving 485 tons. Now, another 49 tons was saved by reducing the nominal 5" ammunition supply, as well as 39.77 tons of drill ammunition. Somewhat more in accordance with the spirit of the rules, 71.46 tons was saved by not counting boats that were only carried in peacetime, 94.7 tons of water in the machinery was eliminated, as was 16.5 tons of lubricating oil, and 101 tons of potable water weight was reduced by assuming that only 5 gallons was needed per man, thanks to the powerful distilling plant. Lastly, 45 tons of stores were not counted for various reasons. This shaved off approximately 400 tons with no actual change to the weight of the ship, and brought the design within the treaty limits.

South Dakota and Alabama operating together in the Atlantic

Two ships, South Dakota and Indiana, were ordered on April 4th, 1938 under the FY39 program, while the deteriorating international situation lead to two more, Massachusetts and Alabama, being ordered on June 25th under a Deficiency Authorization. By this point, the Escalator Clause of the London Treaty had been invoked and the Iowa design was in work, but Congress had only authorized 35,000 ton ships, which meant repeat SoDaks. South Dakota was configured as a fleet flagship, which cost her two of the ten twin 5" mounts the other ships carried. All four ships completed substantially overweight, mostly due to the addition of radar and greatly increased light anti-aircraft batteries.

Indiana bombarding Japan, with Massachusetts in the background

All four ships were rushed to completion in the months after Pearl Harbor, and served throughout the war. Both Massachusetts and South Dakota had the chance to engage enemy battleships. Massachusetts, while covering the landings at Casablanca, engaged the incomplete French battleship Jean Bart. South Dakota fought alongside Washington at Guadalcanal, and while electrical problems resulted in her radar being knocked out and she was badly battered by the Japanese, she stood up to the punishment very well. All except Indiana served in the Atlantic, and all four helped screen the carriers during the final years of the war. After the war, they were quickly decommissioned, and remained in reserve until the 1960s. Both Massachusetts and Alabama were preserved by their namesake states as war memorials. I've been to see both, and they're very much worth a visit.

Massachusetts at Battleship Cove

Ultimately, the South Dakotas were a superlative design. The American designers, having already made a first attempt at a 35,000 ton battleship, sat down again, and made the best battleship ever built that met the requirements of the original treaty. The SoDaks combined reasonable speed, good protection, and excellent firepower, and the design was good enough that the next class, the Iowas, were essentially a stretched version to gain more speed. There were a few drawbacks, most notably poor underwater protection and inadequate space, but in an overall ranking of battleships, the South Dakotas are clearly superior to all except their successors, the Iowas.

1 To mitigate this problem, the designers also looked into the use of water-excluding material, which would limit flooding outboard of the belt. No suitable material was found, and so the plan was never implemented. ⇑

2 This slot was intended as a catwalk to give access to the fuel tanks. The Iowas have a similar slot, but it was plated over. ⇑

3 One of my biggest impressions after touring Alabama and Massachusetts is how cramped they are compared to Iowa. Some of this is because of the 80s refit, which substantially decreased the crew, but a lot of it dates back to WWII. I was astonished when Bill Hood told me we were on broadway, the main fore-and-aft passage under the armored deck. On Iowa, it's probably twice as wide as a standard passageway. On Massachusetts, it looked just like a normal one. ⇑

Comments

I'm confused by the seaplanes. Why put those on a battleship? It seems to me that even firing the guns as intended would destroy them, let alone receiving fire.

I assume they are for scouting - but why not put them on a destroyer or even a dedicated seaplane tender, something that might make the seaplanes less disposable? That would have had the secondary benefit of saving some tonnage on the limited vessel, moving it to a ship not bound by treaty.

The primary role of battleship seaplanes, at least in the USN (British practice differed significantly, to say nothing of the Japanese, who I don't understand very well) was for gunfire spotting. If the battle was being fought at really long range, it was going to be extraordinarily difficult for the shipboard fire-control team to see where the shells were landing and correct for it. So they carried planes which could be higher and further forward and do the job for them. In practice, it worked OK, but not great, although I don't think the planes were formally landed during the war (actually somewhat surprising, given the drive for more AA guns). The problem with offloading these kind of roles is that there's always a fear of the relevant platforms being snatched away. A seaplane-carrying destroyer sounds great, right up until she doesn't get built or ends up getting sent to the Aleutians while your battleship is headed for Guadalcanal with no long-range spot in sight.

In all of this, keep in mind that aircraft in WWII were much more expendable than aircraft today. Because of the rate of technological progress, they just weren't expected to last very long, and there was a good chance that the OS2Us you lost when you had to fire your guns at a bad angle for them were already a slightly outdated model, and the net result is that the ship's aviation detachment gets an upgrade slightly sooner.

This is something I really should write more on, but haven't gotten around to yet.

Okay, trying to wrap my head around that hull... Do I have this correct? https://pasteboard.co/I60hHDv.gif

And was it necessary to descend into the skegs to perform maintenance?

You’ve got the parts labeled correctly. I tried looking for drydock photos, but while there were a couple, they didn't show the whole after hull all that well. Try here for one of Indiana.

As far as I know, the skegs were entirely wet, and any work in them was done by divers or in drydock.

Glad I got that right... so to confirm, 'outboard' and 'inboard' mean 'lateral' and 'medial' on this kind of ship and have no relation to the meaning of those terms in the context of a motorboat?

Ohhh.....

Now I get why you were confused. It took me a minute to work out how those terms were used differently in motorboats. (I'm a big-ship guy.)

Yes, "outboard" and "inboard" basically have two meanings, one being lateral vs medial, and the other being inside vs outside. They're distantly related, in that you usually work over the side, so "swing the boat inboard" works either way. Outboard motors are the glaring exception, but a very prominent one.

Necro, but they did actually try putting catapults on a destroyer (USS PRINGLE, USS HALFORD, and USS STEVENS, with the last being the only one to actually test it). Didn't work, for whatever reasons. Marriott covers it some in his book, per this Google link.

First, the necro policy is that necros are allowed and encouraged. I try to write stuff that will have some lasting value, and there's a reason I maintain older posts. So I definitely don't mind discussions of it.

On the topic at hand, I'd forgotten, but now that you mention it, I have heard of that. Looking in Battleship and Cruiser Aircraft of the United States Navy (don't have the Marriott book, but probably will soon) it seems that the biggest issue was just that a destroyer wasn't a very good platform for the job. It was too small to safely do recoveries, and the massive avgas tank was understandably unpopular. They did use at least one destroyer (an old flush-decker) to refuel and rearm battleship and cruiser spotting planes in the last year or so of the war, so the big ships didn't have to go do it themselves.

Torpedoes were a a greater threat to BBs than other Battleships for most of the war. The Montna class reverted back to the NC TDS system as a result of the Washington/Indiana bunmp up..."Few realized at the time how close the Indiana was in danger of sinking, With thanks to the damage control party that shored up the third deck bulkhead #128 1/2 that held, the Indiana remained afloat. The damage sustained by the Indiana occurred at the most vulnerable location within the armored citadel length. Indeed, a detailed vulnerability study conducted early in 1945 concluded that, if the unprotected stern were riddled, flooding the third deck area between bulkheads 113 and 128 ½ would probably result in a South Dakota-class battleship sinking by the stern. This is precisely the area were the Indiana was hit by the Washington. In this instance the Indiana's holding bulkhead remained intact and the ship's longitudinal stability was not jeopardized, However, it appears that a very similar collision, involving damage to the stern as well as this critical compartment, possibly would have been sufficient to cause the ship to sink."

The Washington-Indiana collision is way too late to have had any impact on the Montana design, which was finalized in 1940 and suspended in 1942. But beyond that I'm not too familiar with it, and will take the pointer to look into it more.

FYI the data the armor ratings is based on in the combined fleet best battleships rating has since been found by Nathan to be wrong. He later concluded that the outer hull of the Iowa would not decap an armor piercing round and since the SoDak hull is thinner the same holds true for them.

That being said the ships are still an incredible achievement on 35,000 tons.

“The designers realized that the important factor was not the beam, but the hull’s cross-section. They cut a tunnel out of the bottom of the hull,”

This suggests that the naval architects designing the So Dak class discovered the area rule half a decade before German aeronautical engineers did and a decade and a half before Whitcomb gave it a solid theoretical framework. That would be pretty significant historically. Are you certain that is why the So Dak sterns were designed that way?

The area rule is for trans/supersonic flows, so the two aren't actually that related. And yes, I'm pretty sure. Cite is Friedman's US Battleships An Illustrated Design History.