David Beatty's famous remark about the destruction of two of his ships by catastrophic magazine explosions during the Battle of Jutland sums up the traditional attitude towards one of the battle's most famous aspects. Of the 3,326 men aboard the battlecruisers Indefatigable, Queen Mary, and Invincible, only 17 survived. It's long been believed that the ships themselves were to blame, as they were built with only relatively light armor. Shells supposedly penetrated to the magazines and set them off.1 Recent research has revealed that this was not the case, and the ships were lost primarily due to defects in operation, not design.2

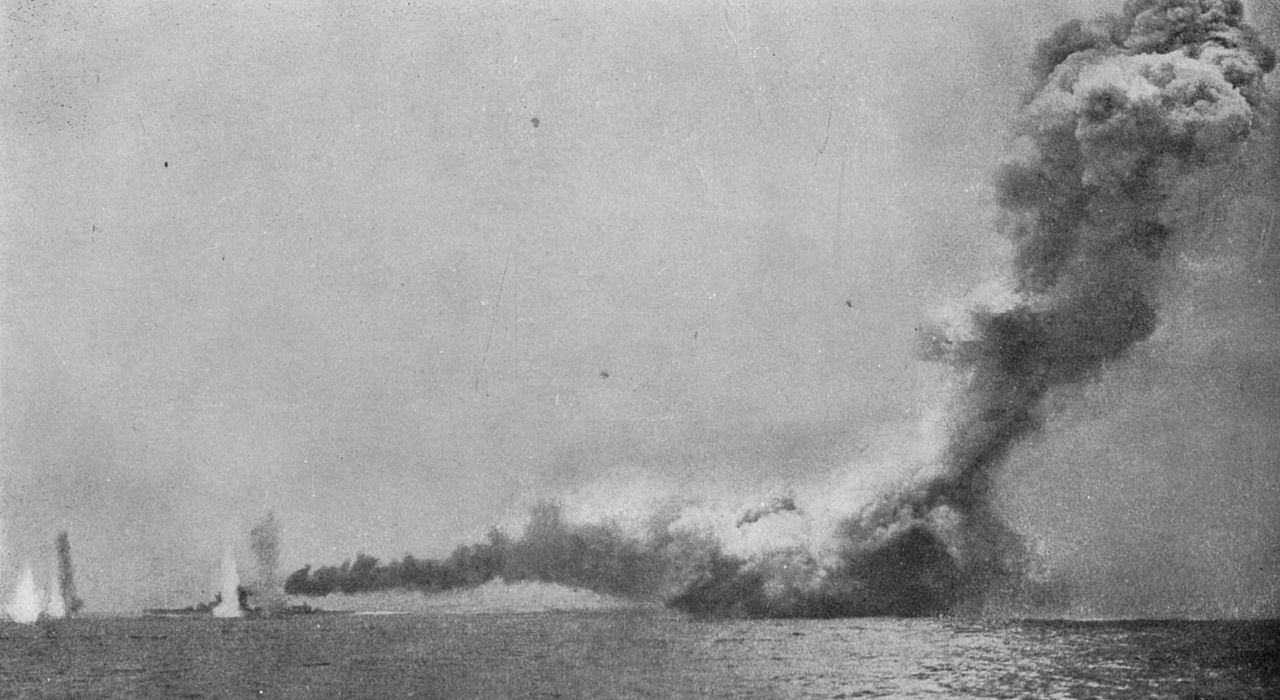

HMS Lion on the left steams past HMS Queen Mary as she explodes

The basic problem with the conventional theory is that no German shell penetrated deep enough into the surviving ships to have been able to set off a magazine if it had hit one. The magazines took up a minority of a battlecruiser's volume, so if such hits were common, then at least a few of the surviving ships should have seen shells reach their machinery. Instead, German shells were found to detonate with 16-24' of their first impact with the structure. At the 20° angle the shells were falling at at the time, this puts them no more than 8 feet below the upper deck upon detonation. The only case where shell fragments reached a magazine was a hit on Barham at 17583 when fragments from a 12" shell penetrated the deck over the 6" magazine. Despite leaving a 12"x15" hole in the 1" deck, the fragments had no effect on the powder stored under it.

Indefatigable sinking

So is there a different potential cause, one that happened to a surviving ship? A survey of the damage to Beatty's battlecruisers reveals a promising candidate. A hit on a turret, such as the one suffered by HMS Lion, could cause a flash to propagate down into the magazine, which would then deflagrate in precisely the manner seen during the battle. A careful examination of Lion's damage shows that she came very close to suffering the same fate.

Invincible blowing up under German fire

Turret explosions are hardly unknown aboard warships, either as a result of accident or enemy action, and a great deal of care goes into making sure that they don't set off the magazines. Powder is stored in metal cans or tanks, and flashproof doors and other interlocks are used to make sure that fire does not reach the magazines. Unfortunately, the British had systematically undermined these protections in the search for rate of fire and ammunition capacity, and their magazine practices during the battle can only be described as suicidal.

Queen Mary's destruction at Jutland

After the Battle of Dogger Bank, Beatty decided that the reason he was unable to destroy the German battlecruisers was insufficient rate of fire.4 Not only would opening fire early and firing quickly lead to early hits, but it would also distract the German gunners. However, the British were not particularly confident in their long-range fire control, and thought they needed extra ammunition to execute these tactics. They thus began to stuff extra cordite into the handling rooms and other spaces that had been designed to provide flash protection. This choice was made much worse by a other changes intended to increase rate of fire. Normally, the cordite cases were kept sealed until just before the charges were sent to the gun, but the crews chose to open many of the cases early, take some cordite out of the cases before battle to make it easy to access, and even stored extra charges completely unprotected.5 In a final effort to make the turrets as dangerous as possible, the majority of the anti-flash safety doors were removed.

Lion's Q Turret after the damaged plate was removed

The only ship which strongly resisted this trend was Lion, and the efforts of her Gunner,6 Alexander Grant, deserve most of the credit. When Grant came aboard, he found the situation described above, and quickly reintroduced the traditional magazine safety regulations with the support of Lion's captain, Ernle Chatfield.7 He managed to train the magazine crews to the point where they could provide cordite to the guns faster than the guns could fire it, while observing full safety procedures.

The damage to Lion's Q Turret after Jutland

During the battle, Lion took a hit on Q Turret8 at 1700. The mortally wounded turret commander, Major Francis Harvey, Royal Marines, ordered the magazine flooded moments before he died, and he was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his heroism. Grant arrived in the magazine a few minutes after the hit. His account says he found the magazine already flooded at Harvey's order, while Campbell says that Grant gave the order to flood the magazine.9 In either case, there was initially no sign of trouble, but a few minutes later, after Grant had gone to inspect X turret's magazine, the eight charges that were in the path between the magazine and the turret ignited, killing over sixty of the crew. If the magazine had still been open, and not flooded, it's almost certain that the ship would have been lost. As it was, the magazine doors were badly damaged, and the flash might have penetrated if not for the support of the water. It's not entirely certain why the charges that ultimately exploded were not returned to the magazine, which would have been possible and prevented the explosion.

Cordite being manufactured during WWII

Another contributing factor was the British use of cordite as their propellant. Cordite, so named because it came in long strings, was a double-base propellant, containing nitroglycerine as well as the nitrocellulose of the alternative single-base propellants. This made it much easier to ignite. During tests in WWII, the US discovered that a spherical flash which would ignite one unit of US single-base propellant would set off 75 units of cordite instead.10 Worse, the cordite used in WWI often contained impurities which made it unstable as it aged. When Grant took over as Lion's gunner, he found the cordite in a terrible state, and had it entirely replaced with fresh supplies. In April of 1917, well after Jutland, plans were made to replace much of the aged cordite throughout the fleet with improved propellant subject to a more stringent quality-control process. Unfortunately, the replacement was not fast enough to save the battleship Vanguard, which exploded on June 19th, 1917. The investigation never conclusively determined a cause, but decaying cordite is the leading candidate.11

12" cordite charges

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, magazine regulations were quickly enforced, and flashtight doors were reinstalled. Both Beatty and Jellicoe, who had at least tacitly condoned the practices, quickly began searching for alternative explanations. The fact that the loss of the battlecruisers was not the result of operational errors was one of the few things that they agreed on in the years after the war. Instead, thin deck armor was blamed, over the objections of the British warship constructors, who pointed out that it was almost certainly not the true cause.

The two halves of Invincible stick above the surface in the shallow water where she sank

Ultimately, the loss of the battlecruisers at Jutland was one of the events that defined the type, and the cover story still informs modern perceptions. However, a careful examination of the actual loss of the ships at Jutland supports a very different conclusion. Even the lightly-armored British battlecruisers that didn't blow up survived a surprising amount of punishment and remained operational. The failures that lead to the destruction of Indefatigable, Queen Mary and Invincible were entirely ones of design details and operation, not a fundamental problem with the ships.

1 This actually did happen to Hood, although connecting her to the losses at Jutland doesn't actually work. Her armor was broadly equivalent to the 15" battleships. ⇑

2 I did not look into HMS Defence and HMS Black Prince, also sunk at Jutland by magazine explosions. These ships were older and designed differently, and I might write about them separately. ⇑

3 GMT+1, as I use throughout my coverage of Jutland. ⇑

4 The German battlecruiser Seydlitz suffered a major turret fire at Dogger Bank, and the lessons learned about flashproofing there are commonly credited with helping their ships avoid the fate of the British at Jutland. This isn't true. German safety features at Jutland were no better than the British, and the fire aboard Seydlitz consumed 14,332 lb of propellant, while Lion was almost sunk by 2,344 lb going up. ⇑

5 There's some confusion as to what actually went on. Every source is unambiguous that the crew did something bad with the cordite cases, although they don't agree on what. Friedman claims that the charges normally stayed in the cases until they reached the guns, and the cases were sent back down to pile up around the base of the hoists. Discarding the cases in this scenario would significantly reduce clutter, which is not the case for just opening them up, which is what Grant seems to indicate they were doing. Grant only indicates they were opening cases early, and it does not align with my general understanding of the safety mechanisms of British turrets. DK Brown also seems to share Grant's understanding, and John Roberts suggests that the cases were permanently fixed to the rack, and the problem was both early opening and early removal/bare storage. ⇑

6 A senior warrant officer responsible for ordnance equipment. ⇑

7 Grant's account of his time as Gunner aboard Lion can be found here and is well worth a read, though he does buy into the theory of the shell reaching the magazine. ⇑

8 Lion’s four turrets were designated A, B, Q, and X from fore to aft. ⇑

9 Lion’s A turret magazine had been inadvertently flooded at Dogger Bank, and they were aiming to avoid a repeat of that incident, so Campbell claims that flooding orders required confirmation. ⇑

10 In fairness to the British, they had conducted some tests before the war, and had thought that cordite was relatively safe. The major flaw was that no tests of confined cordite were made, and some worrying results were ignored. After the battle, the immortal rule "Cordite is safe, so long as you remember that it is dangerous" was promulgated. ⇑

Comments

This was discussed on SSC, without any good answers coming up, but have you encountered anything since on why the British insisted on using cordite instead of the more stable propellants everybody else seems to have used?

I don't really have anything new on the subject, although it may be worth a look through a few books I didn't go through when writing this.

To be an incredible pedant, at least one source I've read claims Beatty said that after a ship didn't blow up (the Princess Royal mistakenly reporten as the third sudden casualty.)

You and many others have remarked that the Germans are just not an aquatic breed, but Massie has left me really wondering if the Brits were. Between this, the gunnery and signal mistakes at Dogger Bank & Scarborough, just about everything at Coronel...it seems that the UK consistently could have executed much better at just about everything, and gave up a lot of great opportunities in the process (not to mention lost many good ships and sailors.)

@Andrew

Incredible pedantry is always welcome here. I haven't read much on Jutland in the past year, certainly not something like Massie. But I'm not going to change the post, because I'm not sure you're right, and narrative wins in this case.

Re the British, you're not entirely wrong. A friend of mine says that if there's any way to screw something up, the British will find it, and he's not entirely wrong. The British had some fairly bad operational and design screwups, but at the same time, I've come to believe that the techniques to resist those kinds of things well were only developed 75-100 years ago. But I'd say that the USN was in a significantly better operational place than the British 100 years ago. Since WWII, he British have moved on to the sort of weird strategic choices that were previously the specialty of the Germans.

@Protagoras

There were a couple of things going on here. In 1901, when the British adopted Cordite MD, the powers using single-base propellants were having serious problems with stability. As best I can tell, it may have been the best option at the time. But it had been passed over the next few years, and the British were locked in.

They traced the problems with stability to impurities. Better quality control helped by 1917, and in the 20s, they switched to a completely different formulation in the same shape. The big problem is that the form is bad. Strings are worse than perforated grains. I suspect they stuck with single-base to keep it backwards-compatible, but neither of my books provides proof.

The connection between these two ideas is unclear to me. Can you expand on how bad fire control leads to extra cordite?

My interpretation was that they wanted fast followup shots because they didn't believe the initial volleys would hit. Hence, stacking ammo within hands' reach.

The British chemical industry was, famously, well behind the Germans at this point. But of course they needed to match German firepower. So maybe compromises were made in propellant technology because they were trying to punch above their weight?

@Rolf

Basically, the tactics the British were using required more ammo than the tactics they'd designed the ships around. Long-range fire is less accurate than short-range fire, which means that you need to use more of it for a given number of hits. If your magazines aren't big enough, you have to get clever.

@Anonymous

That was part of the motive for rapid fire. The other part was that they expected near-misses to interfere with the target's gunnery.

@doctorpat

Yes and no. Everyone but the British went for single-base powders, even if the Germans got slightly better performance out of them. That said, they weren't totally safe. The German pre-dreadnought Pommern was lost to a magazine explosion at Jutland after a torpedo hit. But Seydlitz suffered a major propellant fire at Dogger Bank, with several times as much powder burning as burned on Lion, and survived. (The proported improvements to German procedures after Dogger Bank are largely untrue, by the way. They were equal to or behind the British in flashproofing at the time of Jutland.)

One might wonder about everyone's quality control for shell production, as well as for charge production, given the number of shells at Jutland that were duds or otherwise failed to explode. (And even later; for instance, one of Bismarck's shells ended up in the bottom of Prince of Wales and was only found when the ship was docked after the battle; had its fuse worked properly, it might have set off a magazine from underneath IIRC.

I wonder how much of this was waiting for the development of proper statistical analysis techniques so people could have a reasonable chance that sampling a few shells would reveal the quality of the batch.

The big problem there was fuses, which are really hard to test well. Shells were often tested unfused and filled with sand, because that made it easier to analyze the penetration testing. Solid shells were pretty common up through the 1890s, IIRC, so there wasn't a lot of concern about behind-armor effects. I assume this attitude carried over later, for reasons I can't explain. There were also issues with oblique testing of shells for various reasons. It's something I should probably read up on.

Did it actually do this? And if not, did the British expect their own gunnery to also suffer from near-misses, or were they assuming other nations just lacked their upper-lip-stiffness to deal with splashes?

It did interfere to some degree. Probably not as much as they would have wanted, but shells falling short throw up a lot of spray, and that gets in the way of sightlines and distracts the crew. Remember that they had access to a lot of reports from the Russo-Japanese war, which was only 10 years before, and most of the theories were based on that.

If the German handling procedures were as bad as the British at the time of Jutland, why did they not suffer the same level of critical existence failure? Was it just luck?

No. Much of their propellant was in metal casings (the back half of the charge, IIRC) and the chemistry was such that it ignited more slowly even when it wasn't. That meant that a much bigger turret fire at Dogger Bank wasn't lethal for Seydlitz, while Lion came very close to blowing up at Jutland. The important thing is to make sure that what happens isn't a runaway chain reaction, and that it burns slowly enough that you don't see a pressure buildup.

For some reason, this post is attracting a lot of spam, so I've closed the comments. This is not an exception to my pro-necro policy, and if you want to talk about it, let me know by posting in the latest OT.