The Tomahawk missile has been one of the most influential developments in naval warfare over the past half-century. While it began as a nuclear missile, and was soon developed for anti-ship roles, the most famous version of the Tomahawk, and the only one to remain in inventory today, is the conventional TLAM (Tomahawk Land Attack Missile). The TLAM gives conventional surface ships and submarines the sort of inland reach and firepower that was previously only available to carriers.

Iowa launching a Tomahawk

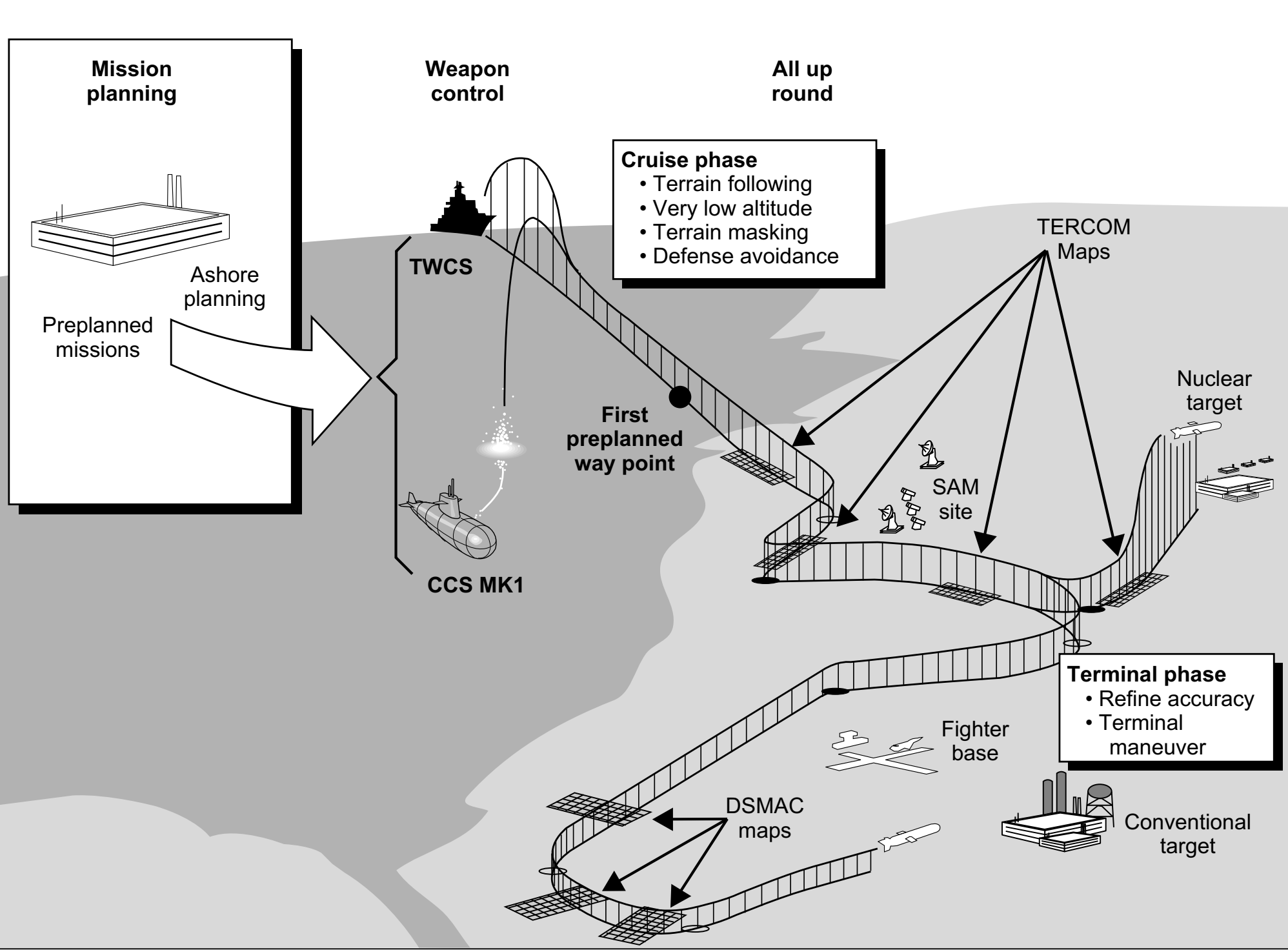

Developing the TLAM wasn't as simple as mating the guidance system from the nuclear version with the warhead of the anti-ship Tomahawk. While the TERCOM1 guidance system was perfectly adequate for a missile with a nuclear warhead, it couldn't get the missile close enough for the 1,000 lb warhead to be effective. Another, similar technique known as DSMAC (Digital Scene Matching Area Correlator) was used to bridge the gap. This was essentially a camera on the missile that would provide an image to be compared to a stored file of processed satellite imagery. By matching the two, the missile could figure out where it was with even greater precision, and the technique is fairly robust against changes within the image. This is possible because the missile isn't looking for the target directly, but is instead using the data to update its estimated position, and then flying to the pre-planned target coordinates. To make sure that DSMAC could still work at night, the missile was fitted with a strobe light.

A TLAM-C destroys an A-5 Vigilante during a test

All of this was enough to get the missile within 6-10 m of the target, but it had several serious drawbacks. Producing the TERCOM maps and DSMAC scenes took a great deal of work, which made it impossible to respond to a fast-moving crisis of the type that dominated the post-Cold War world. When Saddam rolled into Kuwait in August 1990, the Navy began working around the clock to build Tomahawk targeting data, an effort that took until December. Even when it was completed, the options available to targeters were still limited. Missiles fired by ships in the Mediterranean had to fly circuitous paths to pick up the necessary TERCOM data, and there were only a few available routes for missiles going into Baghdad, a fact exploited by the Iraqis, who positioned AA guns along them and shot down a number of the incoming missiles.

Nor was building the actual routes a trivial task. The limited computing power of the late-70s targeting systems meant that the work was done at two facilities ashore, one in Virginia and one in Hawaii. The targeters would attempt to build routes that avoided enemy defenses while taking into account the Tomahawk's very limited rate of climb, a result of the small, fuel-efficient turbofan engine. This was essentially a trial-and-error process, and routes often ran into dead ends and had to be thrown out and rebuilt. Once a route was finished, it was loaded on an 80-lb hard drive and delivered to the force flagship, usually a carrier, who would then pass it on to the firing ship via helicopter. The only option available to the firing ship was the exact aimpoint, which could be updated within a limited area.

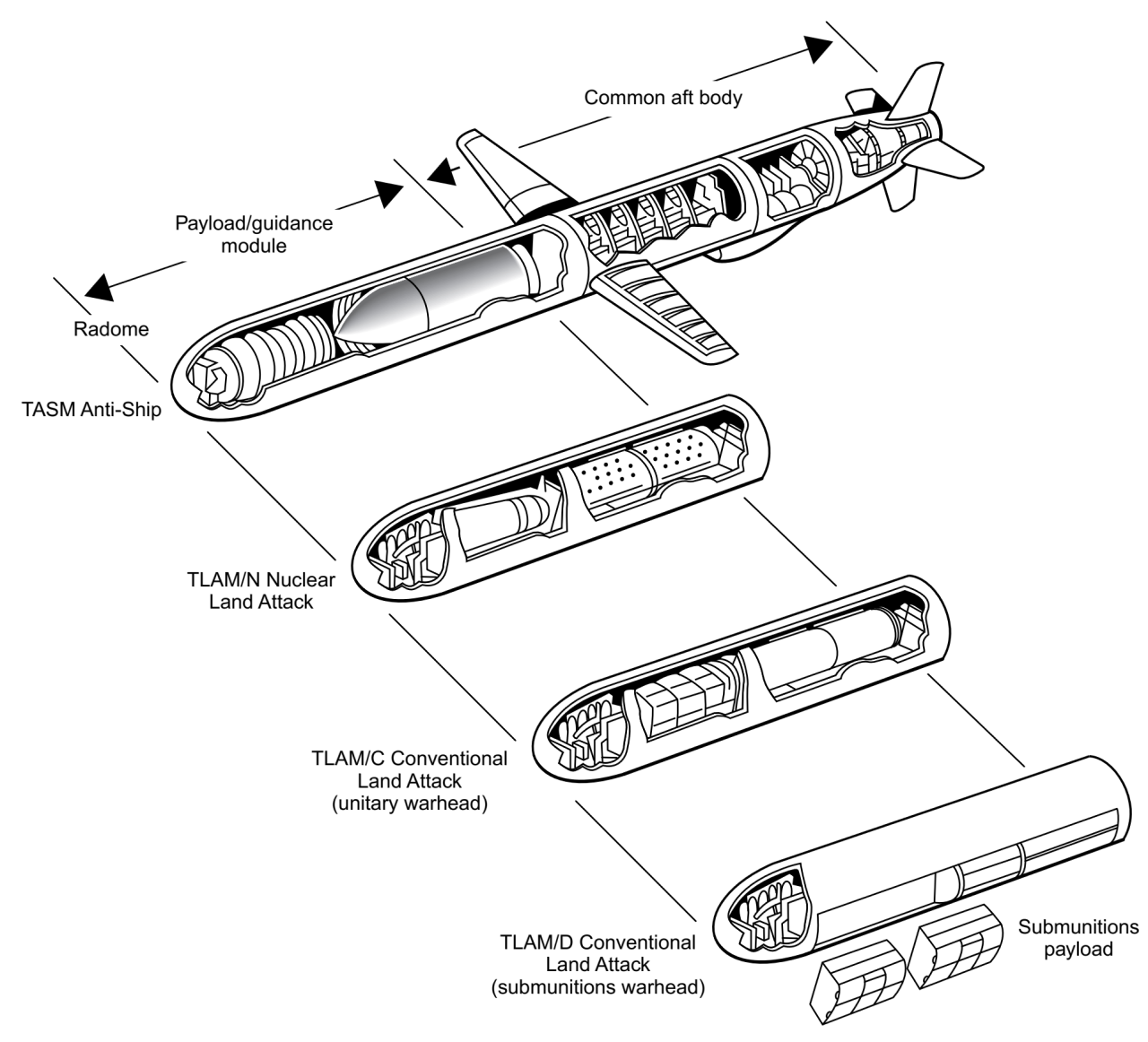

The early Tomahawk variants together

The RGM/UGM-109C TLAM-C entered service in 1986, intended to take out hard unitary targets. It was followed two years later by the RGM/UGM-109D TLAM-D, which replaced the conventional warhead with a submunition dispenser to attack softer area targets like airfields and troop concentrations. It had a total of 166 BLU-97 combined effects bomblets, equipped for anti-personnel, anti-armor and incendiary effects. A few TLAM-Ds were equipped instead with submunitions containing carbon-fiber filaments, intended to short out electrical distribution equipment. Both missiles could reach out to a range of about 600 nautical miles, although this might be reduced by circuitous flight paths, either to pick up TERCOM data or to evade defenses.

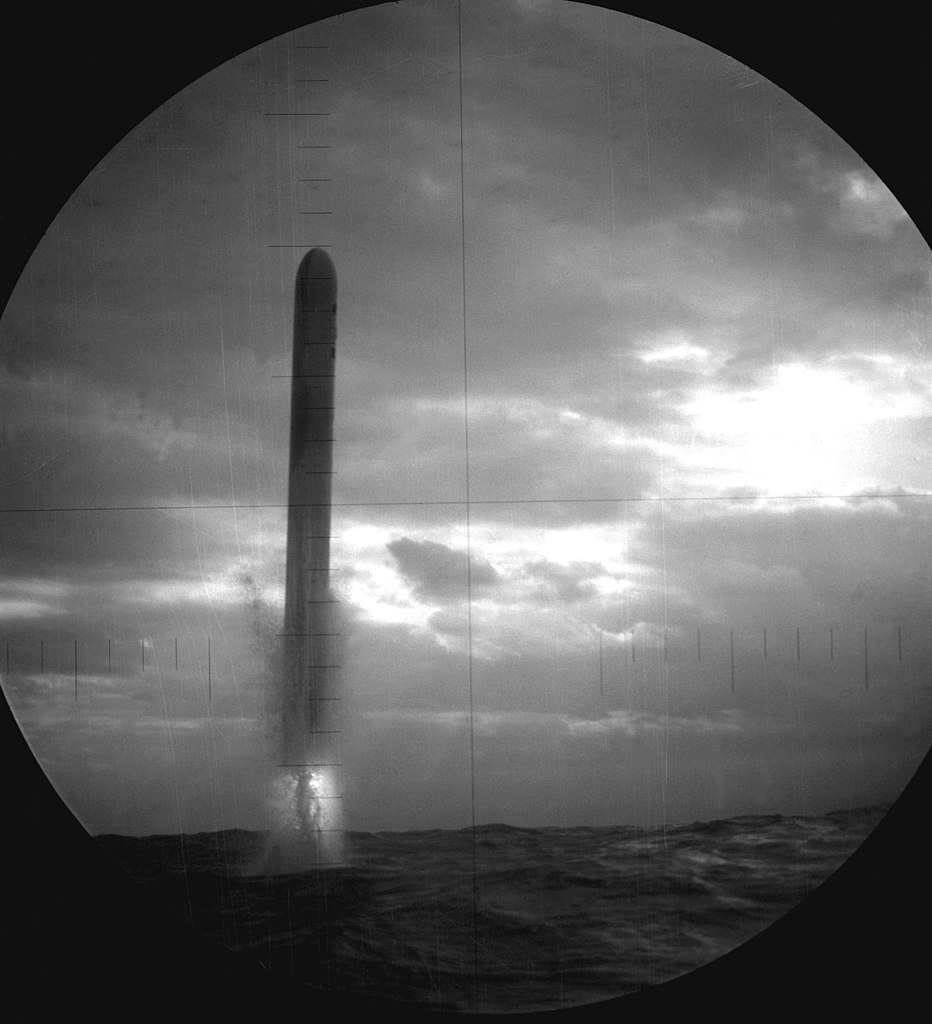

Missouri sends a Tomahawk to Baghdad

Tomahawk's baptism of fire came in 1991, when it played a key part in the air campaign against Saddam's regime. Used for missions judged too hazardous for manned aircraft, it was the only means of striking targets in Baghdad during daylight. The first wave of 52 missiles, fired on the morning of January 17th, saw 51 hits on the targets, and included weapons from the battleships Missouri and Wisconsin. By the end of the 18th, 218 had been launched from 8 ships, and the next day saw the first submarine-launched Tomahawks from Louisville and Pittsburgh. These were some of the 70 launched during the rest of the war, as Saddam's air defenses collapsed. The weapon was judged a major success, with only six missiles failing to transition to cruise, and accuracy equivalent to manned aircraft, without the risk to pilots, and contracts were quickly issued to rebuild the TLAM stockpile, a third of which had been expended.

A Tomahawk launch, seen through Pittsburgh's periscope

TLAM's combat debut had been wildly successful, and more was to come for this weapon. Block II would see combat twice more, with President Bush launching 46 against an Iraqi nuclear facility two years to the day after its combat debut. Saddam's regime got another 25 in June in retaliation for a plot to assassinate former President Bush. But even as the missiles filled the skies over Baghdad for the first time, a new version known as Block III was being tested. This would increase the missile's utility and make it a favorite weapon of five successive administrations. We'll look at it next time.

1 Terrain Contour Matching, a system that would read the terrain below the missile and compare it to a digital chart to figure out where the missile was. ⇑

Comments

there were only a few available routes for missiles going into Baghdad, a fact exploited by the Iraqis, who positioned AA guns along them and shot down a number of the incoming missiles.

I guess they just worked this out from observing that all the missiles came the same way? They didn't have actual knowledge of the maps.

It sounds like you could mess up the system using good old fashioned barrage balloons.

I don't know how much they knew about the TERCOM/DSMAC system, so I'd guess it was just someone noticing "hey, the missiles all are coming in the same way". None of my sources indicate anything about them stealing maps, which would have been a lot more difficult.

As for barrage balloons, interesting idea, but probably not. Remember, CEP for TERCOM is ~50m, while DSMAC can't do better than 5. So that's the best positional accuracy you can expect, and it's wide enough (particularly because Tomahawk is a lot smaller than manned aircraft) to make barrage balloons not work quite so well.

That seems like it'd make Tomahawk pretty easy to spot by ground-based visual observers, right? Just look for the bright blinking light and phone HQ, letting them know there's a cruise missile on the way.

DSMAC didn't kick in until it was pretty close to the target, and I'd guess the theory was that it wouldn't give enough warning to make a meaningful difference in terms of letting HQ give useful orders. In terms of giving away the missile's position directly, people are surprisingly bad at pinpointing strobes at night. They'll know the general direction, but not much more.

The idea that the cruise missiles use headlights to see where they are going at night is too amusing to not have crept into popular culture.

Why aren't we seeing cartoon missiles with lights?

@quanticle

If there are no other references, just seeing a strobe flash is not enough to give an observer path information.

If a light is fixed, the viewer can be susceptible to the so called auto kinetic effect/illusion in which the light appears to move. The "moving" smoke detector light in a darkened room demonstrates this.

Related to this effect, is if the light is moving but there are no other reference points. The viewer can get the impression that the light might be moving in any number of directions. Sound can help rectify this a bit as can, obviously, other lights, but even then at night it is still hard and open to gross errors by observers. I am not sure what the Iraqi forces were doing to determine flight paths but they must have had something else to help them.

I mention all this for it was the Navy that started serious research into this in the mid 1940's while studying vertigo and they uncovered a lot of interesting facets to the erroneous interpretations the eyes/brain make in such situations.

Did Baghdad do a proper blackout, or did they decide there was no point due to their enemies night vision capabilities? If the lights were on maybe they'd have been able to use them to get their bearings. Then again, if the missiles could get a 50m CEP without the strobe, then as Bean said, it's turned on so late that it gives no useful warning.

Don't know about the blackout, but I suspect that the strobes would still be used. I think DSMAC relies on reasonably uniform lighting, and having some areas lit up and others in shadow would really throw it.

Ah, no, I meant that the Iraqis could use them to help work out where the strobes were, by giving the spotters some reference points.

That sounds like it would be solvable with a stabilized launcher (copy the Talos or Terrier design? or if intimidating looks are psychologically effective enough to be worth the money, a "gun turret" with torpedo tube barrels?), or possibly by just launching when the ship is level. Which makes it weird that they didn't, ~50 years after they automated both of those for guns. Would that not have worked? Or was sometimes having to wait for better weather unimportant enough for a strike weapon that they didn't really care?

Wisconsin was Tomahawk coordinator for the Gulf War, but I don't know if she had this upgrade. (The Iowas apparently did at least get the ability to download plans by satellite rather than having them physically delivered.) I find it amusing that two fire control systems that both pushed the limits of their time's computing technology, which were very different because those times were ~40 years apart, could have been on the same ship.

Oh, sure, in theory it would be possible to stabilize the missile launcher, but you're looking at a massive increase in the size, weight and cost of the ABL. At some point, it's just not worth the tradeoff.

I'm sure that they took this as far as they could. It takes the missile time to clear the launcher, and if the ship is moving too much and too unpredictably, it could get damaged or thrown into the sea. Keep in mind that I don't have any details on the motion limits for these launchers, just reports that they were sometimes exceeded in the far northern seas, particularly for ships smaller than the Iowas.

Re the coordination system, the exact details and stages of that were quite complicated, and I didn't go into detail to keep from boring everyone to death.