"I have discovered a marvelous proof of the difference between turrets and barbettes, the margin of which this book is too small to contain" - Scott Alexander

When I wrote about ironclads, pre-dreadnoughts, and the development of heavy guns, I made reference to a rather unusual theory about the development of heavy gun mountings in the 1885-1900 period. Now, I've finally gotten around to writing it up in full. I apologize if this is rather more boring and technical than usual, but I'm challenging the conventional view of the subject, rather than simply reporting it.

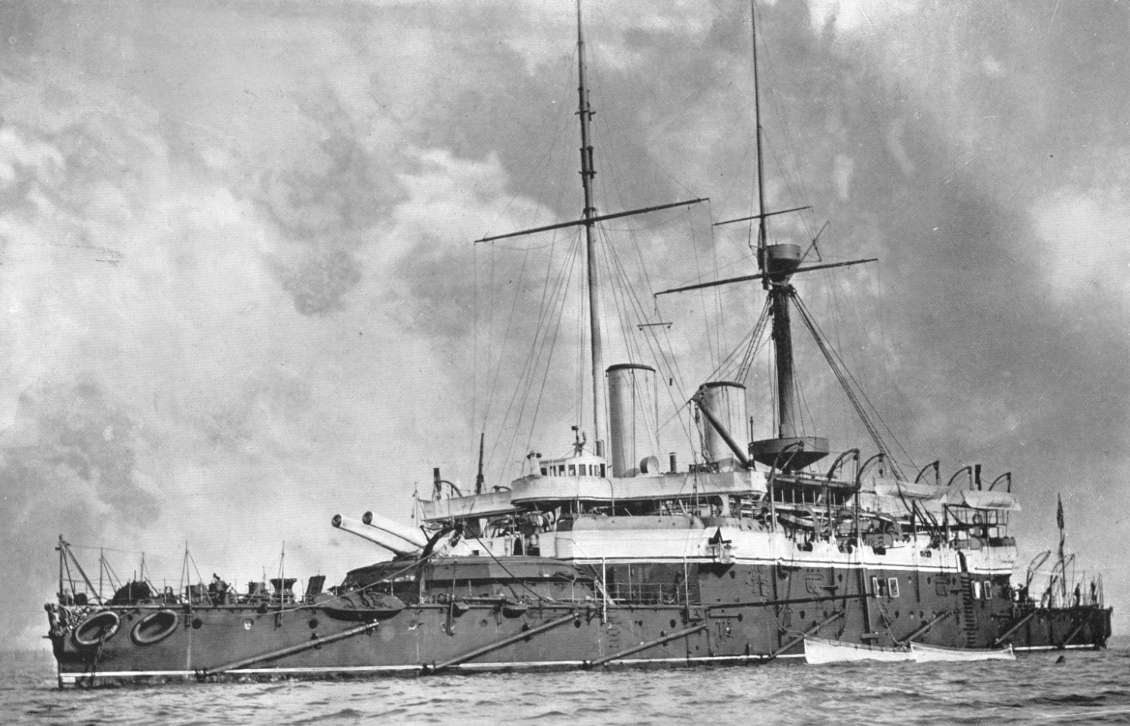

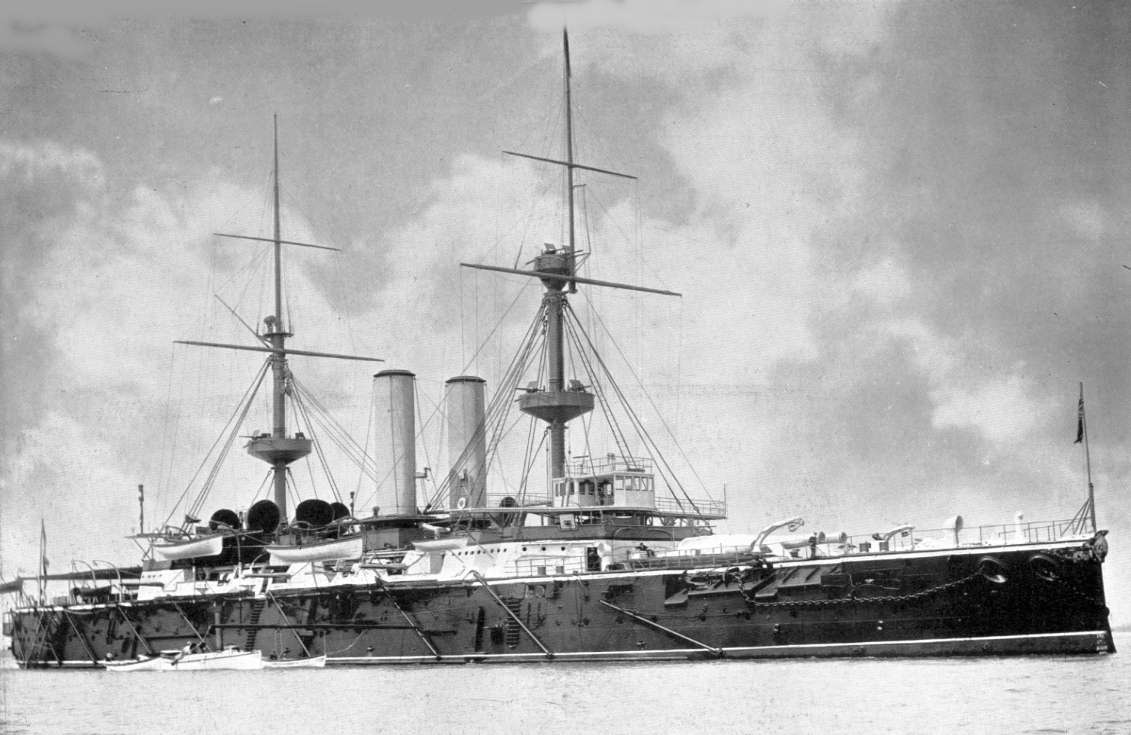

HMS Anson, an early British barbette ship

The conventional wisdom is that original-style turrets were heavy and had to be mounted low, while barbettes allowed guns to be mounted much higher and eventually replaced turrets. Gunhouses were then installed, resulting in mountings that look like turrets but fundamentally differ from the original versions used through the 1800s. I repeated this version in my SSC post on pre-dreadnought history, and several readers started asking probing questions on this. I began to dig, and I've since come to the conclusion that the conventional wisdom is wrong, and that the real picture of how gun mountings developed is much more complicated.

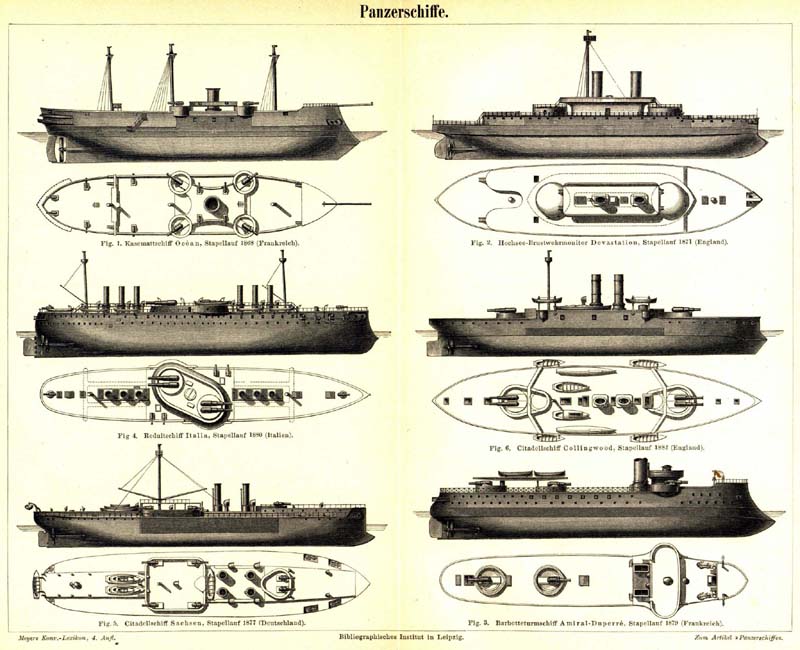

A selection of ironclads with different weapon mountings1

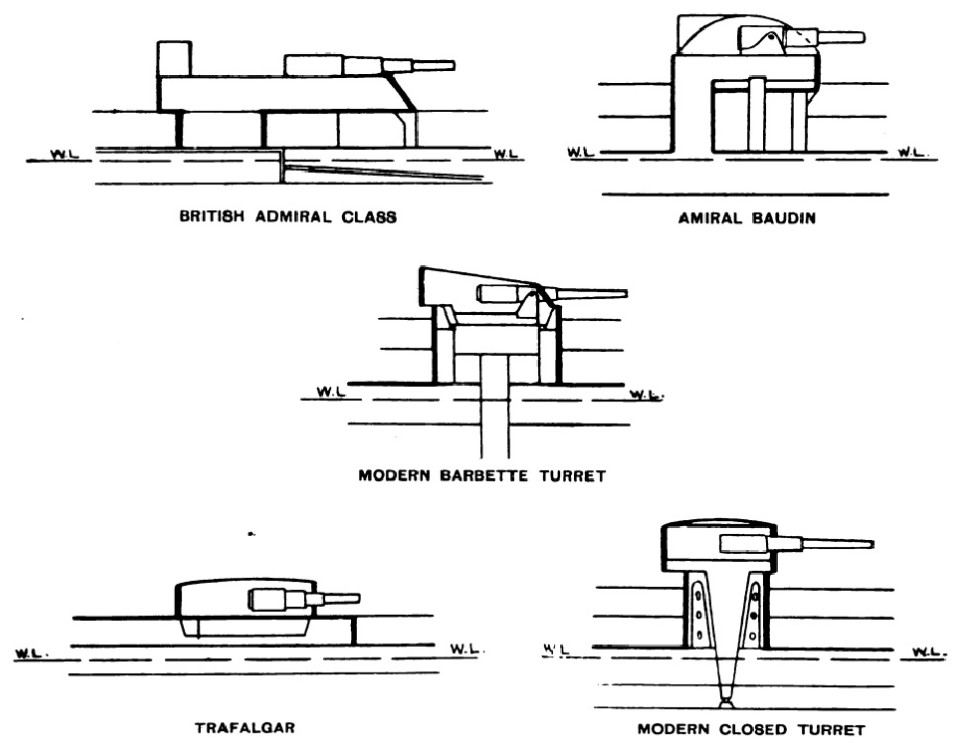

One of the biggest problems is that the use of the term 'barbette' was and is incredibly sloppy. A conventional turret can be more or less defined as a round mounting that is protected with heavy (belt-thickness) armor.2 Anything that isn't a conventional turret is usually called a barbette,3 despite major differences in armor arrangement and mounting design. An outline of the variants will be illustrative.4

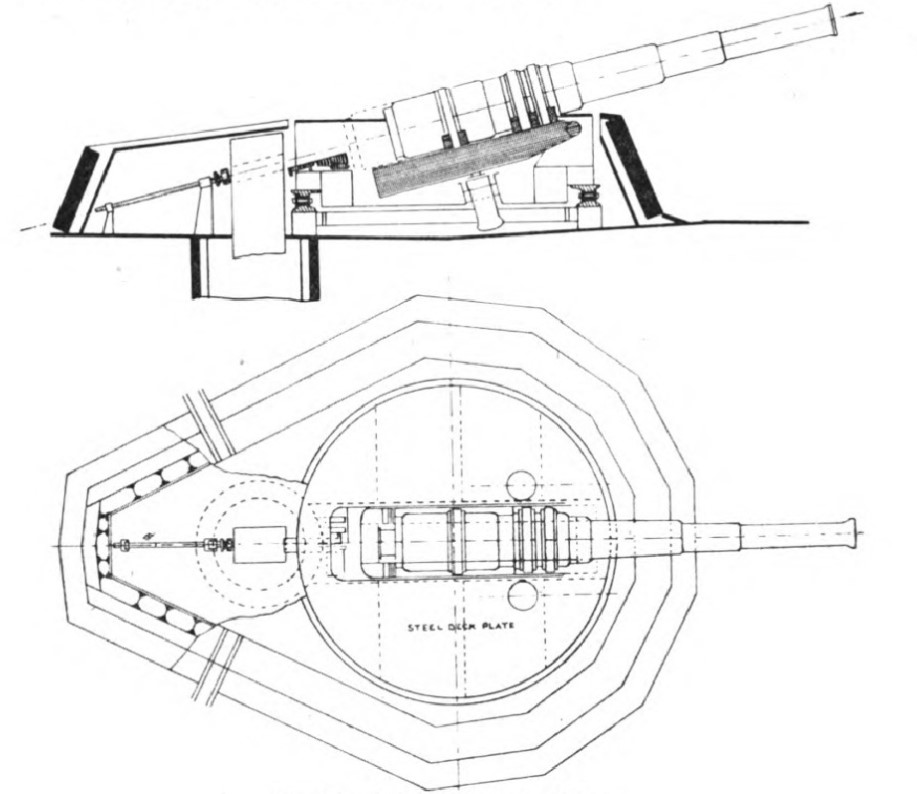

A diagram of a barbette similar to that fitted to the Admiral class

The earliest barbettes were essentially armored tubs on the upper deck of the ship, with small tubes running down to the magazines, most famously used in the British Admiral class. These were open-topped, with the guns firing over the edge. To give the crew at least some protection, the guns were loaded at a high angle of elevation, placing the breeches inside the tub. The bottom of the barbette was often unarmored, making it vulnerable to shells bursting below it, and even when it was armored, the foundations were still exposed to QF gunfire. The French and Russians fitted at least some of the barbettes of this type with thin hoods to provide protection from the very light QF guns of the day, although the British never did.5

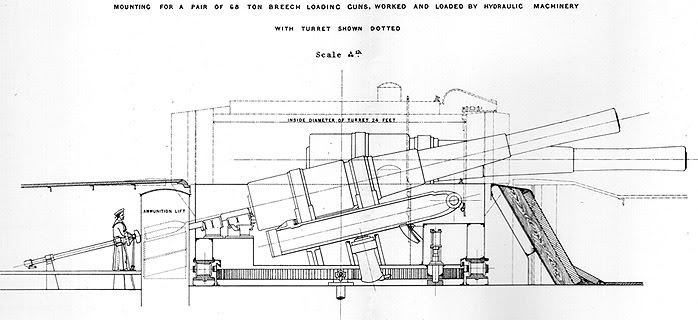

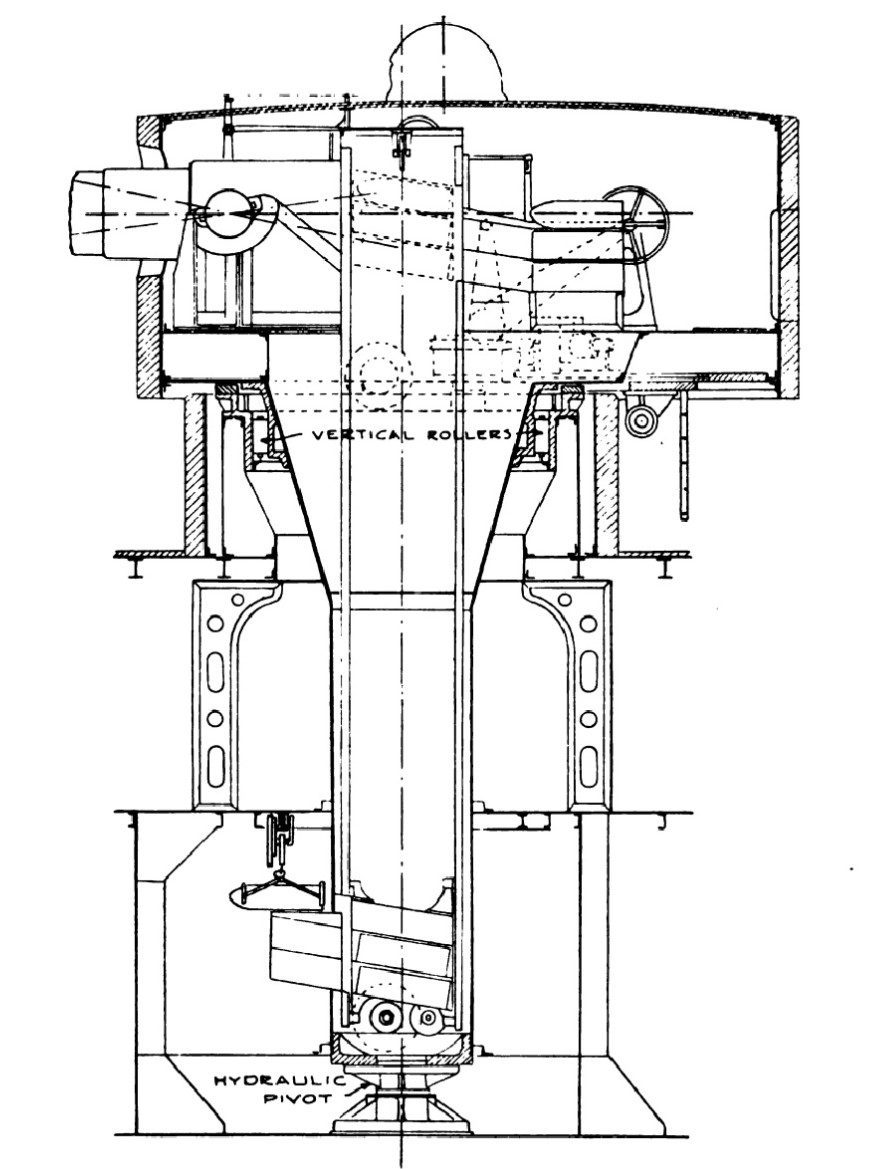

Comparison of turret and barbette mountings for 13.5" gun

The biggest advantage of this arrangement is that it requires significantly less topweight than a turret with the guns at the same height.6 At the time, turrets sat directly on the armored deck, which would have had to be carried, belts and all, to the same height as the barbette was mounted. In addition, the heavy turret body was essentially moved down somewhat to form the body of the barbette, with the net result that a given quantity of firepower could be carried on a significantly smaller (and thus cheaper) barbette ship.

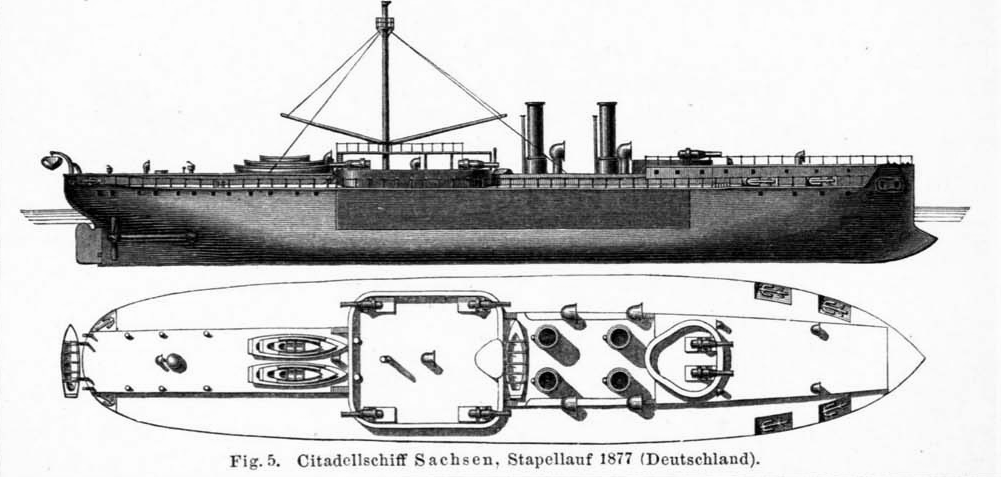

German ironclad Sachsen

The Russians and the Germans used a very different system, where there were no separate barbettes, and the guns were protected by the ship's citadel. This can be seen on the Russian Ekaterina II class and the German Sachsen class. This obviously does not have the same topweight benefit of lowering the citadel, although it does eliminate the turret armor itself. The Russians, at least, adopted this mounting on the Ekaterina II class because they wanted high-angle capability for shore bombardment, which was not possible from turrets at the time. The ship was modified from a turret design relatively late in the design process, which may account for why they chose a citadel design instead of using tub barbettes. I'm not sure of the reasons behind the German decision to adopt it.

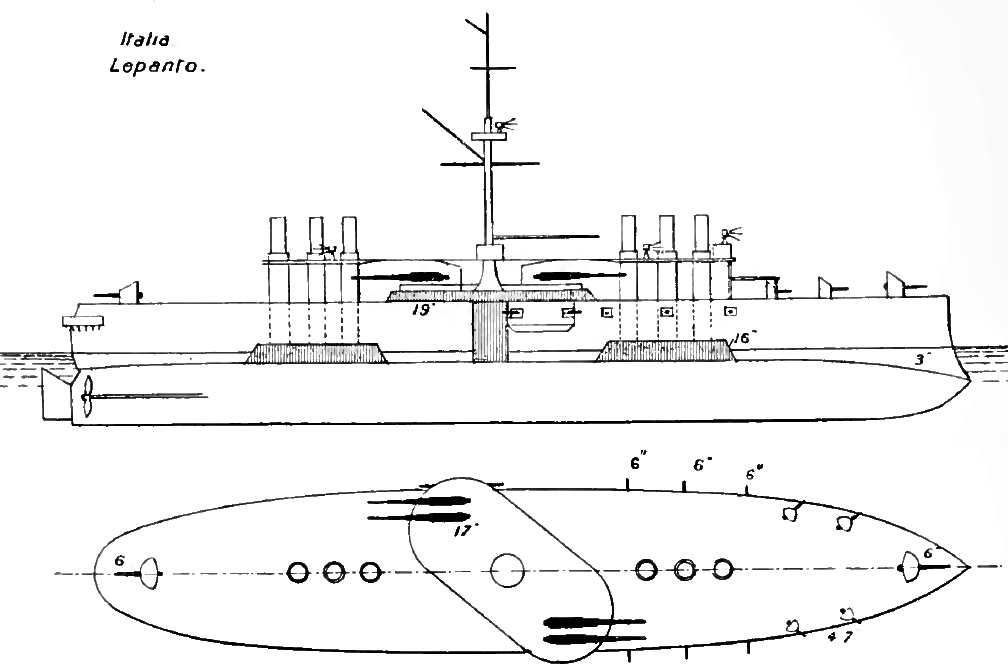

The Italia class

The Italians used a variant of the tub on their Italia class. In this case, the two twin mounts were protected by a common barbette, which ran diagonally across the ship. I have no solid information on the reasons for this choice, but it's possible that because of how close together the guns were, this was more weight-efficient than separate barbettes.

The British developed another style, which struck a balance between the demand for low topweight and the need for protection against shells bursting below. This was first used on the Royal Sovereign class, and essentially extended the barbette down to the armored deck.7 This was called a redoubt barbette, as the area immediately above the armored deck was somewhat larger than the rest of the barbette profile for reasons that are not immediately apparent.

HMS Royal Sovereign

The obvious way to get a turret higher above the waterline was to mount it on a redoubt of its own, and this approach was in fact pioneered on the Cerbere class ironclad rams of the late 1860s by French constructor Dupuy de Lome. For some reason, this innovation was mostly ignored, and it didn't reappear until the sketch designs for HMS Victoria, although that ship's single turret meant that it wasn't apparent in the finished design.8 Some thought this compromised protection, so the Trafalgars didn't use it, but it was used on HMS Hood, a turret-armed version of the Royal Sovereign.

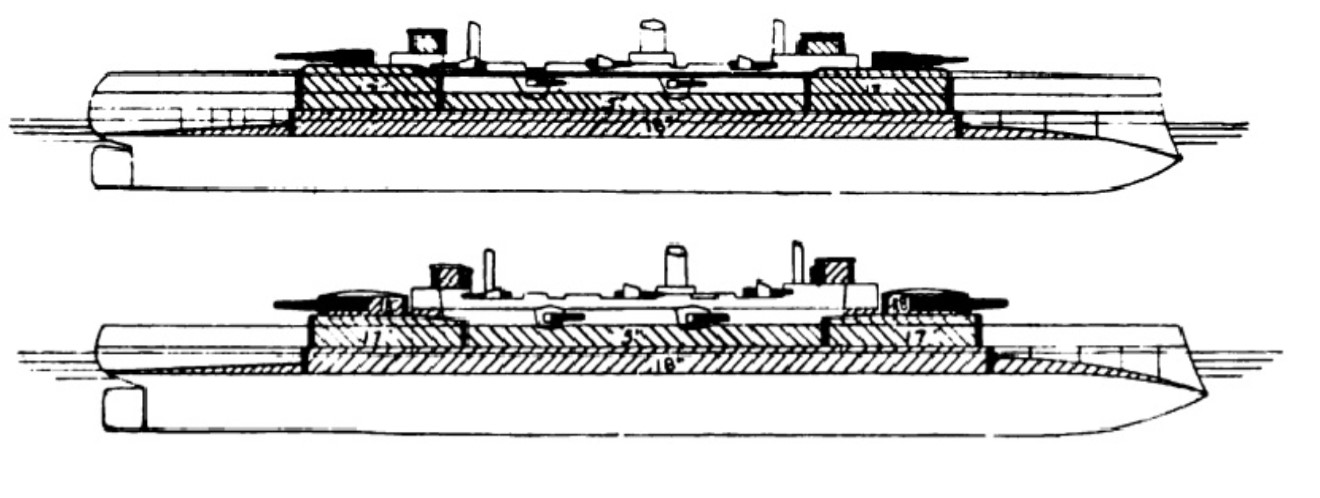

Royal Sovereign (top) and Hood

Hood was a thoughtful gesture on the part of the RN, providing a control for naval historians trying to figure out this question 130 years later. A look at a cross-section of the two classes shows quite clearly that they both carry the same armor to the same height. The only difference is where the guns are mounted relative to the armor. Hood had hers within the armored cylinder, while the barbette-mounted guns were on top of the armor. The weight figures in R. A. Burt, British Battleships 1889-1904, bear this out. The barbettes on the Royal Sovereign weighed 1,345 tons, presumably including the redoubts. The turrets on Hood weighed 1,490 tons.

Early gunhouse on HMS Renown

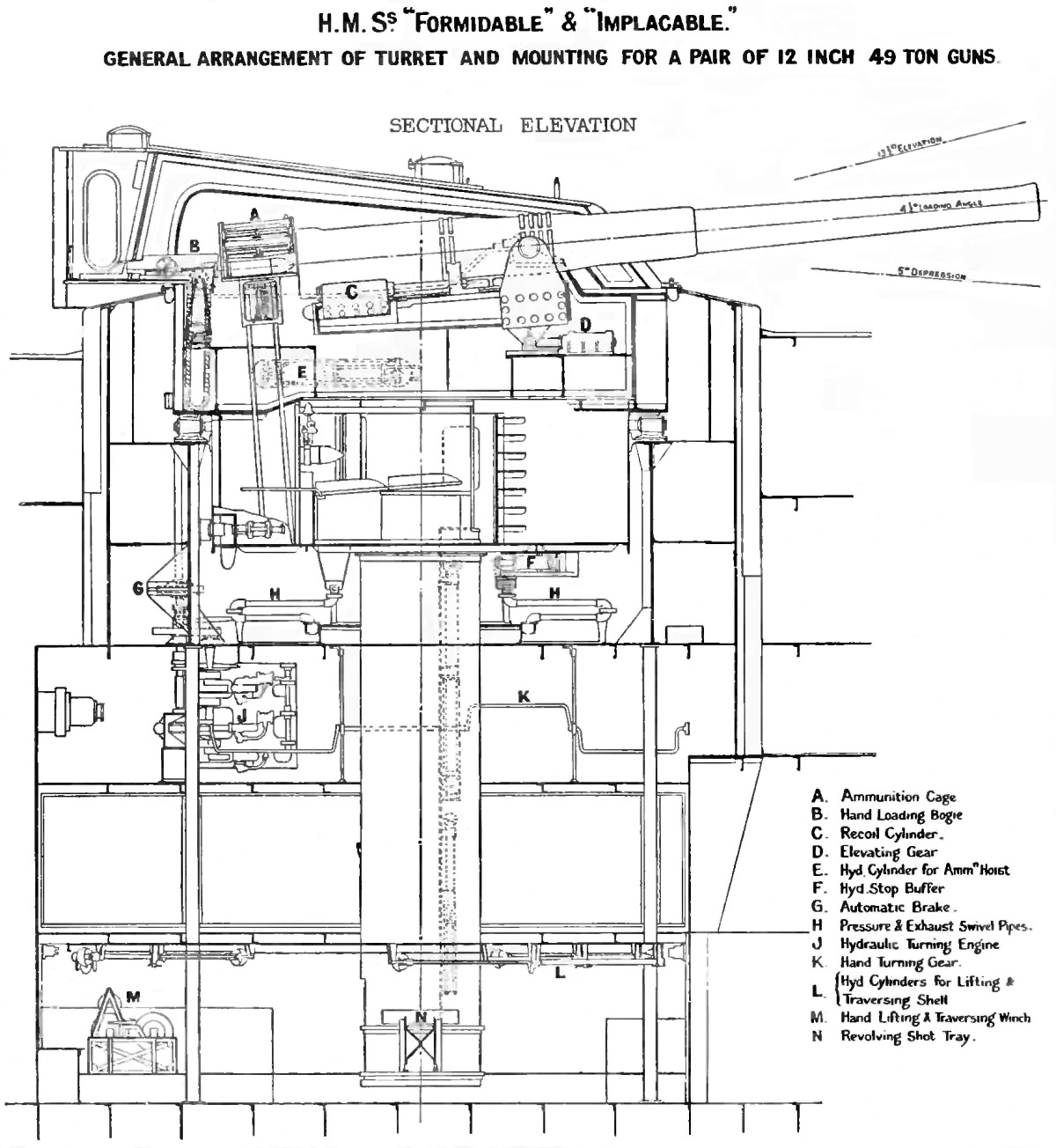

The class after the Royal Sovereigns, the Majestics, were fitted with what were known as gunhouses, somewhat lightly armored compared to the barbettes, but a recognizable step back towards the turret.9 Later British battleships had thicker gunhouses, and the sloped armor on the turret faces provided protection approximately equal to that of the barbettes.10 An inspection of the diagram will show that much of the protection was provided by the barbette, but even as early as Majestic, important functions were being performed entirely within the rotating structure. Friedman ties the gunhouse on the Majestic to the development of all-around loading, which required equipment to be fitted above the level of the barbette.

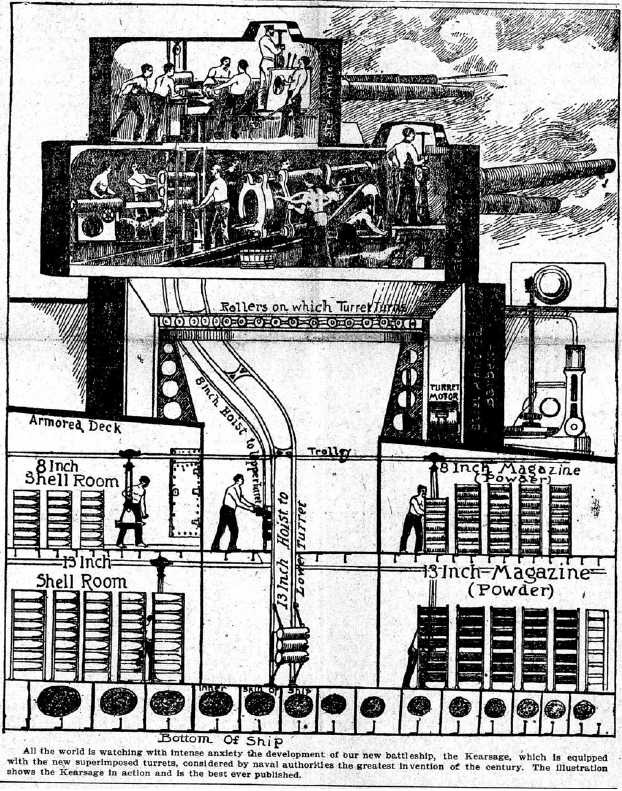

Diagram of turrets on Kearsage class

But why isn't being contained within the rotating structure a good test? Weren't all turrets loaded entirely from within the turret itself?11 This is what Stephen McLaughlin proposed in his Russian & Soviet Battleships, but it fails when it's tried on turrets outside of Russian and France. In the Mk II turrets of the US Indiana class, the loading mechanism was mounted in the non-rotating part of the turret, as it was in the turrets of Victoria. However, these are universally agreed to be turrets, with Norman Friedman, in US Naval Weapons, and Peter Hodges, in The Big Gun, agreeing that it was done in the Illinois class of the mid-1890s. However, American Battleships 1886-1923 says of this that the only major difference between the Mk III mounts of the previous class and the Mk IVs of the Illinois were unequal-length recoil cylinders needed to accommodate the sloped faceplate, and Naval Weapons of WWI describes the mountings in the Iowa class12 as being barbette mounts, despite the loading mechanism having been moved entirely inside the turret body. The definitive US Battleships - An Illustrated Design History doesn't mention any changes in the gun mounts of the Illinois, beyond discarding the superimposed turret of the previous class. On the other side of the Atlantic, the BVII(S) mounts of the King Edward VII class pre-dreadnought had the rammer entirely within the turret.13 For that matter, the turrets on HMS Colossus, one of the first British battleships to use breech-loading guns, had externally-mounted rammers.

A typical French turret

The nation that is most consistently said to have stuck with the turret was France, and its turrets were different from those of other nations. Instead of the shells coming up the hoists into position behind the guns, they came up directly under the guns, then were moved to the side and taken on rails to the loading position. French turrets also had uniquely narrow trunks, significantly smaller than the turret that sat atop them,in contrast to the turrets of the British and Americans. Peter Hodges stated that this arrangement was no heavier than the contemporary British design, but did have a higher center of gravity. This is entirely believable, given the arrangement of both mounts, but also a major blow against the standard theory. The only other user of the French-style turrets was the Russians, and any tests that distinguish it from contemporary British or American mountings produce nonsense results when applied outside that domain.

The turret of a King George V class battleship during WWII. Note the fact that the faceplate is continuous at the bottom of the port, but not the top.

The source I've found that comes closest to my theory is William Hovgaard, who described mounts after Majestic as "barbette-turrets", although he claims that they remained distinct from previous turrets because the gunports went all the way to the bottom of the shield. This meant that the guns technically fired en barbette. In 1920, when his book was published, it was at least arguable that all British turrets were designed this way, but later British turrets, most notably those on the King George V class,14 did not have this feature. It was certainly not ubiquitous on ships of other navies.

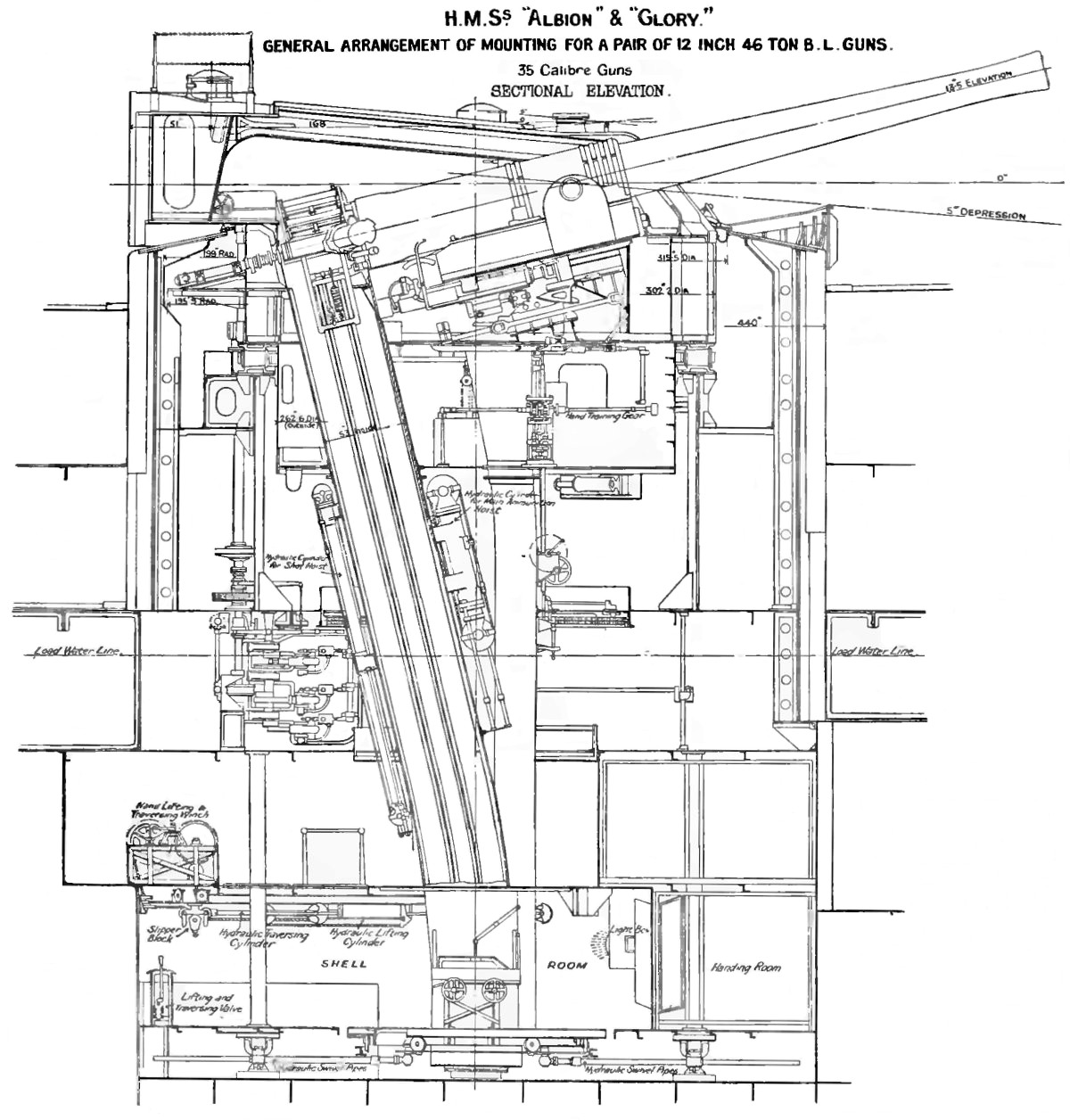

An early British pre-dreadnought turret, from the Canopus class

So what drove the changes in mounting design in the 1890s? Why could turrets suddenly be mounted much higher in the ship? There were several major factors in this change. First, armor was developing rapidly, making protection against battleship guns much lighter. Harvey armor, introduced on the Majestics, allowed their barbettes to be cut from 18" to 14", which alone is probably enough to allow the gunhouses. Second, the round turret became obsolete with the development of all-around loading. Previously, it had made sense to provide equal and heavy protection for all sides of a turret, as an enemy might see the side of the turret as it trained to a different bearing to reload. With all-around loading, a heavy faceplate could be kept trained towards the enemy, and the sides of the turret, which would likely only take glancing hits or smaller-caliber weapons fire, could be made thinner. It's possible that part of the French retention of the round turret was due to the belief that they would be heavily outnumbered in a battle with the British, and subject to fire from multiple angles.15 Third, ships were becoming larger, increasing their ability to carry topweight. Until the introduction of the pre-dreadnought, the British spent most of their time trying to cram as much firepower as possible into a small hull. This meant they were forced to choose between protection and gun height. Majestic, 15% larger than Royal Sovereign and with thinner armor, could provide both.

A later British turret, from the Formidable class

So why do most sources vigorously insist on the distinction between turrets and barbettes? I believe this goes back to British naval politics at the time. There was a faction, lead by First Sea Lord Arthur Hood, who favored the low-freeboard turret ship instead of the high-freeboard barbette ship. For this group, low freeboard was not simply a response to the excessive topweight of high turrets, it was considered important in and of itself to reduce target profile. When Hood retired in 1889, this faction lost almost all of its influence. However, I believe that the conflict caused the term "turret" to be conflated with low freeboard, and as a result, the RN spent the next decade claiming that the new mountings were in no way related to the disgraced turrets.16 By that point, those involved in the conflict had mostly retired, and the word turret came back into general use.

A comparison of different mounting arrangements17

But if this was a purely RN conflict, and had no relevance in other nations, why is the distinction so widespread? The simple answer is that naval design history of that era is the history of the RN. There are only a handful of books which cover even American battleships of the late 1800s, and the situation is worse for non-Anglophone powers, most of which have only a volume or two of relevant history available in English. Even the authors of those works are from the British-derived tradition, and seem to have not reevaluated the traditional narrative in light of worldwide experience.

Ultimately, the designers of warships and gun mountings in the late 1800s had a number of options to choose from. Simplifying these options available into "turret" and "barbette" significantly understates the complexity of the process, and creates a dichotomy where there was none, particularly in countries outside of the United Kingdom.

1 The top-left ship is the French Ocean, the first ship to carry barbettes. They were hung over the side of the ship, to allow end-on fire without interfering with the rigging. ⇑

2 "Is it round?" is by far the best test for whether a reference book will classify something as a turret or a barbette mount. None of them use it explicitly, because it sounds unscientific, but in practice, it's more accurate than any other method. ⇑

3 It also refers to the fixed armored tube that modern turrets sit atop, adding to the confusion when similar structures aboard older ships are discussed. ⇑

4 I've included all of the ones I know about. It's possible that I missed some, which I will add as I learn of them. ⇑

5 There was a school of thought which believed that being exposed would be good for morale because the men could see the enemy, and that turrets were a bad idea because of this. ⇑

6 Higher guns are easier to use in bad weather, and some of the early turret ships had their guns so low they flooded at high speed, even in calm seas. William Hovgaard also suggests that higher guns could fire onto the thin decks of enemy ships, and that this was seen as important. This is an interesting theory, but one I have no confirmation on. ⇑

7 In British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Friedman distinguishes between the barbette and the structure below it, which he calls a "ring bulkhead". Other sources treat this as simply part of the barbette. ⇑

8 Norman Friedman mentions that there was talk of the follow-on Admiral class having turrets above their barbettes. I couldn't find a sketch, and and his description isn't very detailed, but it appears that the turret would be mounted on the existing barbette, which in that class was unprotected below. ⇑

9 This actually began with the 10" weapons on HMS Centurion, a second-class contemporary of the Royal Sovereigns, which had open-backed 6" shields. This was because the 10" guns were hand-worked, and that meant a lot more men exposed than on the power-operated guns of the Royal Sovereigns. The initial plan for the Majestics was to fit a light shield for protection if the emergency hand-loading system had to be used, but detailed design raised the trunions above the barbette, forcing the designers to increase gunhouse thickness. ⇑

10 Actually, this was true even on the Majestic. ⇑

11 Well, apart from the muzzle-loaders of old. ⇑

12 BB-4, not BB-61. ⇑

13 It could be argued that enough of the loading mechanism was in the level below the gun that this doesn't apply, but at that point, we need a model that's a lot finer-grained than just turret/barbette. ⇑

14 Strictly speaking, this is true of either the 1911 or 1939 classes, but the cutout at the bottom of the former was very narrow. ⇑

15 Round turrets were also necessary for their unique loading mechanism, but they substituted a more conventional system on their first dreadnoughts. It's interesting to note that those ships were the first design after the Anglo-French Entente, although I'd be careful about drawing too strong of a correlation there. ⇑

16 There was also other prejudice against turrets, most notably the belief that men inside turrets would not fight as well as those exposed in barbettes. It's possible that the avoidance of the word "turret" was a way of pandering to these beliefs even as they were reintroduced in practice. ⇑

17 This diagram, like several others I've used, comes from Hovgaard's Modern History of Warships. He draws a distinction between proper turrets and barbette-turrets. As best I can tell, this distinction is mostly between single-stage and two-stage hoists, but the US, not shown here, used single-stage hoists on all of its dreadnoughts. ⇑

Comments

Don't apologize, these are the best pieces.

Good God, people are stupid.

@redRover

Much appreciated. I honestly wasn't sure if this would make sense, or if it was just a bunch of rambling on minutiae that nobody cared about.

@Gazeboist

I usually try to find a reason for those kind of ideas, but that one is basically indefensible.

I'm going to try to defend this as best I can, without actually endorsing it. In modern writing about war there is this concept of the "empty battlefield", of infantrymen having so much firepower (both personally and on-call) that they have to spread out very far, and take a lot of cover, and you end up with apparently empty landscapes being immensely dangerous. And this is considered a morale problem, in that when you cannot see the enemy you're fighting, then being unable to see any enemies does not mean you're safe - so, you're never safe.

I suggest, then, that the proposed morale effect of barbettes is not from being exposed, per se, but from being able to see the enemy. (Obviously this assumes fighting at visual range, but that's fair enough for the 1880s and 1890s). The suggestion is, perhaps, that men who are basically industrial workers except that an enemy shell might break in on them at any moment, may have some difficulty thinking of themselves as fighting, relative to men who can see what they're shooting at and perhaps even the effect they're having. This may not be true, but it's not quite as obviously stupid as "being exposed improves morale" - it should be expressed the other way, "being enclosed (and blind) depresses morale".

Being able to see the enemy was definitely the root of that idea, which I guess just didn't make it into the post. (Stuff like that happens, particularly when it takes like 11 months of work to write.)

There are a couple of problems with this theory. The first is the tradeoff between protection and exposure. In 1870 or 1880, there's something to be said for letting the crew know what they're looking at. The gun-loading process is still mostly manual, and the risks aren't nearly what they'd be in 1890. There were some light guns for attacking exposed crew early on, but the torpedo threat kicked that into high gear. Most British pre-dreadnoughts, for instance, had fighting tops with a couple of 3 pdr QF guns in them, perfectly placed to rain fire into a barbette. For that matter, the British fitted the barbettes on the Royal Sovereigns with protective covers, so most of the crew couldn't see anyway.

Second, I think you're missing an important part of the "empty battlefield", namely that it's empty of friends as well as enemies. Men fight better when their friends, their squadmates, can see them. It's a lot harder to stay in a nice, safe hole in the ground when your buddies on either side are getting out of theirs, and will see you if you stay. That obviously doesn't apply here, and I think it's the more important half.

Not to mention that there were a lot of men who couldn't see. Your survival might depend on the engineers who kept the engine running, or the stokers shoveling in coal, and they were much more detached from the actual fighting than the turret crews.

Even today, you see military officers forming cults around weird ideas. The FAC people spring most prominently to mind. Yes, they have some arguments, almost all terrible. I suspect this is a long-ago version of the same tendency.

This is attracting a lot of spam for some reason, so I'm closing the comments. If you have a comment on it, post in the latest OT, and I can unlock them.