By late 1942, it was obvious that the Liberty Ships would soon be entering service in huge numbers, decisively winning the tonnage war with the U-boats and providing the cargo lift needed to support the Allies' global war effort. But the Maritime Commission had never been particularly happy with the design. The biggest drawback was that it was simply too slow, and as the supply of steel began to throttle the shipyards, the Commission asked if it wouldn't be possible to design a ship that balanced the speed of production of the Liberty with the greater value of the faster C2 cargo ship, both during the war and afterwards.

Lane Victory in San Pedro

This logic proved compelling, and work began on the design, with a target speed of 15 kts. In most other ways, it would be similar to the Liberty, with extensive use of welding and careful design for ease of production. Cargo capacity would remain around 10,000 tons, and the layout was quite similar, with five holds. Each hold would get an extra deck inside it to make it easier to load cargo, and the deck was strengthened to increase capacity there, even though that meant getting new steel shapes out of the recalcitrant steel companies. As the design progressed, some other quality of life features that had been deleted from the Libertys were restored, such as the gyrocompass and searchlights, so long as they wouldn't delay the planned program. Steam auxiliary equipment gave way to electric, and detail design was improved to deal with the threat of cracking.

But the biggest question was engines. When the Liberty had been designed in 1941, the overriding imperative was speed of production, limiting machinery to a reciprocating steam engine churning out only 2,500 hp. This was less than half the power required for the new type, and the Maritime Commission explored several options. In an ideal world, they would use steam turbines, as was common for fast cargo ships, but despite their best efforts to increase production of marine turbines, it seemed that the growing appetite of other shipbuilding programs had kept pace. Instead, they turned to the Lentz Engine, a steam engine that should be capable of higher powers than standard types. The only problem was that, while it was common in Germany, only one company in America had a license. That in and of itself wasn't a big deal, as German patents obviously weren't being enforced, but it did mean that various parties were rather wary of adopting technology that they didn't have experience with.

SS American Victory in Tampa Bay

It was at about this point in early 1943 that the Maritime Commission's plans came into conflict with the War Production Board. The WPB had appointed William Gibbs of Gibbs and Cox as its head of shipbuilding, and he quickly began to push for the curtailment of the Victory program in favor of more Libertys, which they argued would provide more tonnage without the disruption required to retool for the new design. The Commission argued that their production was primarily limited by steel, and that it made sense to spend extra labor to turn said steel into faster ships that could carry more cargo with less crew. Gibbs also pushed for cuts in the C series of ships, which the Commission took great pride in. Those, they fended off by pointing out that the yards were already tooled up and building them quickly, and any long-term benefits would be outweighed by the short-term costs.

The dispute raged for several months, as the delineation of responsibilities between the two organizations was less than clear, and the only one who could referee the fight was FDR, who encouraged clashes between the organizations responsible for the American war effort. The clashes delayed the switch to the Victory Ship, as the WPB refused to authorize needed plant additions for several months before Roosevelt finally sided with the Commission. But the issue reared again as the supply of turbines became an issue, with the WPB proving helpful in producing a new 6,000 shp turbine for the Victory Ship, and the Maritime Commission having to fight off plans to use the cheaper turbine on the C ships. At one point, things got so bad that the Commission had to send letters from its legal department countermanding orders by the WPB to cancel C series turbines. After a truly insane amount of bureaucratic wrangling, the matter was finally decided in the Commission's favor in August 1943 by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

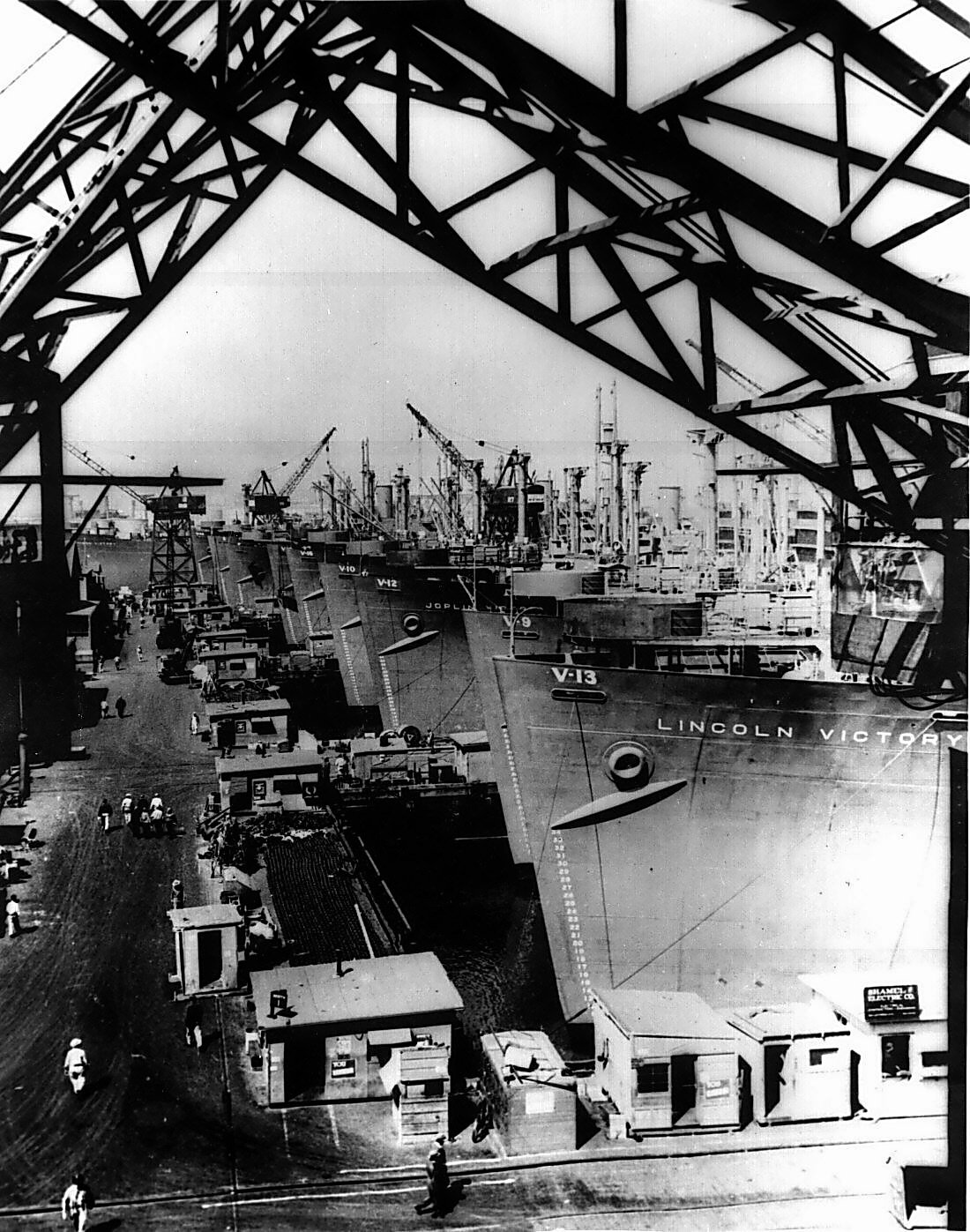

Victory Ships lined up at Oregon Ship

But the result was that the new vessels would be powered by turbine instead of by the Lentz Engine, a mix of the new Victory turbines and turbines designed for the C3 type that were available because the turbine manufacturers were running ahead of the shipbuilding schedule. The new turbine was less efficient than the old one, but significantly easier to build. Among other things, the propeller speed was increased from 92 rpm to 100 rpm, which allowed the gears to be smaller, in turn allowing more gear-cutting machines to be put to use.

The first keel of the new type was laid on November 19th, 1943, at Oregon Ship, on a slip that had just seen a Liberty go down the ways. It took 102 days for SS United Victory to be delivered, a significant improvement over the 226 days it took for Oregon Ship's first Liberty. She was followed by 34 more ships, each bearing the name of an Allied nation, followed by "Victory". With those names exhausted, the US turned first to cities and towns, and then to colleges. As with the Libertys, building times plunged, with Oregon's 28th ship, Escanaba Victory, being laid down only 61 days before her delivery on June 29th. In total 413 of the basic cargo Victory ships would be delivered, plus three more completed to a modified design postwar, although many of them were too late to see much action.

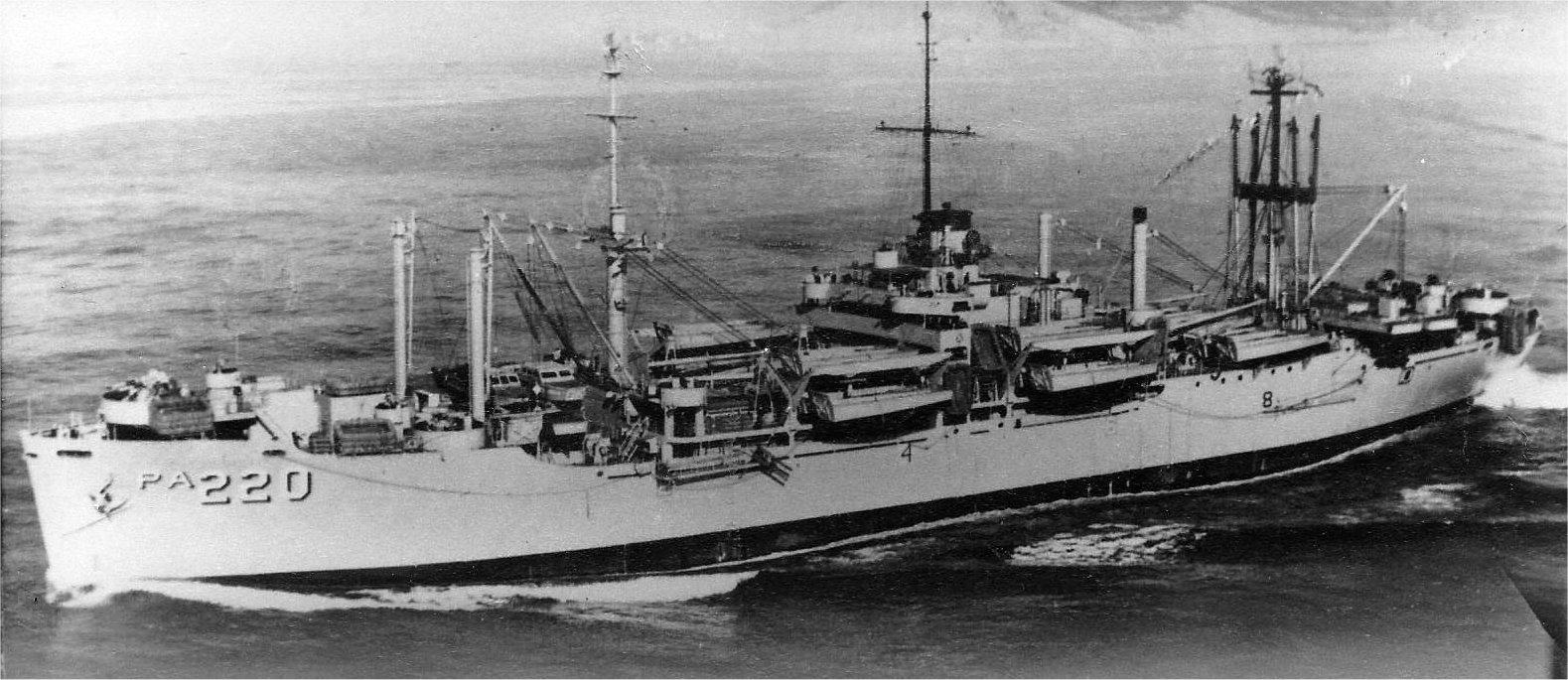

USS Okanogan, a Haskell class attack transport

The speed of the Victory design opened up the possibility of its use as a naval auxiliary, and a total of 117 were built as attack transports of the Haskell class, named after American counties. Each was completed with facilities to carry 1,500 men and to unload them over a hostile beach, although they were quite cramped, as the designers had to cram in as many troops and almost as much cargo as had been carried by the larger C3 troopships the Navy preferred, and the barber, cobbler and tailor shops had to be discarded. To ferry them ashore, each ship carried 23 LCVPs, 2 LCMs, and three other LCVP-sized craft, and the interior was laid out to make it easy to move the troops into their landing craft, a distinct issue with point-to-point troopships when used for amphibious landings. Armament was 1 5"/38, 1 quad Bofors, 4 twin Bofors and 10 Oerlikons. Many of these ships were rushed into service for the later part of the Pacific War, and they made up the majority of the Navy's attack transport fleet into the 60s.

They were far from the only Victory Ships to see postwar service, although production stopped with the defeat of Japan, with the exception of 3 hulls completed for the Alcoa Steamship Company. 72 of the cargo version were sold to American shipowners, and another 100 or so overseas, many of which served on as cargo liners for decades, although their numbers were dwarfed by the Liberty Ship in postwar service. This left the government with about 200 vessels in the reserve fleet, which it used for a variety of purposes. 46 were used postwar by the seagoing cowboys, who carried over 200,000 animals to replenish Europe's war-ravaged herds. Many were reactivated to carry cargo for the wars in Korea and Vietnam. Some had more exciting lives, such as Pratt Victory, torpedoed off Okinawa in the closing days of the war and sailed as an expendable minesweeper to ensure that all the remnants of the American mining campaign against Japan had been removed. This was indeed the case, and she went on to have a long career first in government and then in merchant service.

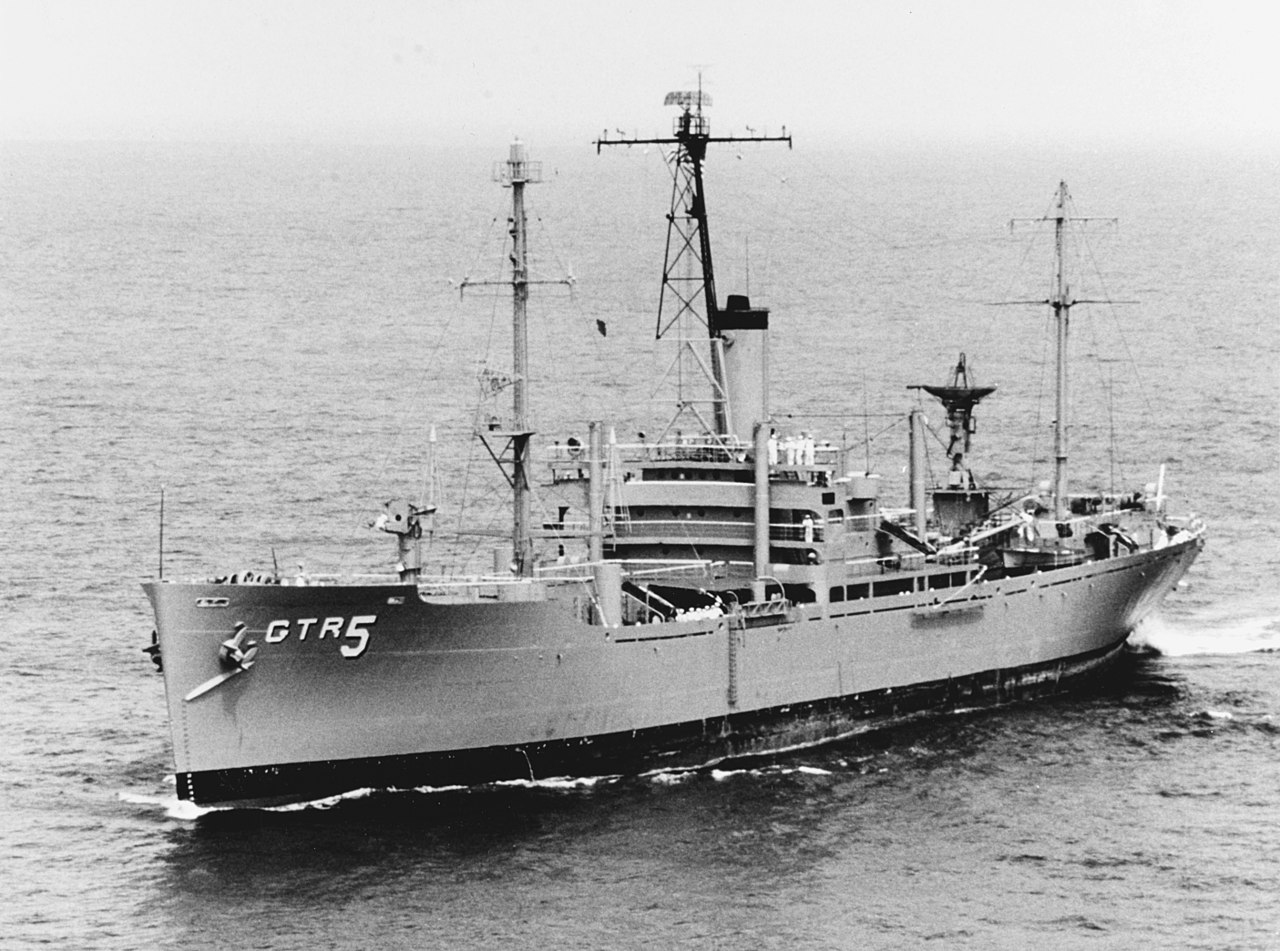

USS Liberty in happier days

Other Victorys were converted into more conventional auxiliary ships, in roles including stores ships, cargo ships for the ballistic missile submarine force, missile tracking and telemetry ships, survey ships and "technical research ships" that researched radar and radio emissions. One of these, USS Liberty, became probably the most famous of the Victory Ships after she was mistakenly attacked by Israeli forces during the Six-Day War, with the loss of 34 of her crew.

Red Oak Victory

But on the whole, the Victory Ship proved an excellent design, if less prominent than its earlier sister. Three remain as museum ships today, American Victory in Tampa, Red Oak Victory in Richmond, California and Lane Victory in San Pedro, not far from the Iowa. All three used to regularly go to sea, although it appears that all three are now crippled by boiler problems. Still, they live on, a reminder of the "bridge of ships" that carried the supplies to fight WWII.

Comments

Should we read anything into there being a SS Czechloslovakia Victory, but not a SS France Victory?

...PRATT VICTORY wasn't the only VICTORY to end up as a minesweeper.

HARRY L. GLUCKSMAN (launched Savannah GA 29 APR 44) was sent to American Shipbuilding in Lorain, OH in 1966 to become the 'ultimate' minesweeper. She was gutted and filled with 140,000 cubic feet of styrofoam.

No, really. My dad was the piping systems supervisor for the job. They spent three years on the conversion, and she was eventually shock tested off Charleston in 1969. Designated MSS-1, she never got a formal hull number or name on the USN roster. Apparently the USN threw everything they could at it and she passed with flying colors - and then the USN cancelled the project, disposing of the ship in '75. Her skipper and crew (she had a total crew of nine) received multiple decorations for their work.

Funny how everyone makes fun of Hitler for doing this, but I don't think I read a single word criticizing Roosevelt's handling of the war in school.

@ike

I had missed that. No clue why France was left out.

@Mike

Glucksman was a Liberty, not a Victory. That said, rather surprised she wasn't used at Hiaphong.

@echo

The US war economy was productive enough that Roosevelt's mismanagement is easy to overlook. Also, dying in office does wonders for a reputation. As for the typo, fixed.

I'm going to mildly push back and say that in this case Roosevelt was right not to intervene. Out of all the people involved in the dispute, he was the least informed and therefore most likely to be wrong. Waiting for the two sides to come to agreement, or one to beat the other into submission, wouldn't lose the war.

Most of the time competing groups are arguing because both have good points. Ideally the process will generate a superior final choice as both sides respond to criticism from the other.

Yes, there is always a danger that they'll lose sight of the end goal (here the best ship) and just want to win the argument by any means. Passing the decision up to a higher authority seems attractive from a time perspective, but then the focus tends to shift to persuading the higher authority that they should favour you, not your proposal.

Nazi Germany R&D during WW2 to me suggests that while the Roosevelt style had occasional glitches, such as the delay here, it was way way more effective overall.

With respect to France, it is probably has something to do with US policy recognizing the pre-war government instead of the rebels for most of the war.

The wording around Pratt Victory needs some cleanup. I reread it seven times wondering how she got herself torpedoed after the war.

@Hugh

The point is less that Roosevelt should have intervened, and more that the structure shouldn't have been set up so that his intervention might be necessary to resolve the issue. Someone below him should have had clear responsibility to resolve the issue, but he chose to keep the US war effort split into squabbling fifedoms.

Interestingly, I have a biography of William Gibbs (read it last year as a library check-out; after moving 1/3rd of the way across the country, I found another copy in the library discard sale). I'll have to check out what it says about his actions here.

ike:

By the time of the Victory ships the US had switched position.

@Bean dying in office does wonders for a reputation.

Well, it didn't help Hitler's much.

@Bean "Someone below him should have had clear responsibility to solve the issue" ... AFAIK one of the primary reasons Robert McNamara was appointed US Sec of Def was to eliminate just such wasteful inter-service squabbling and duplication of effort. I don't think you're a fan?

Yes it's always possible to reform for better outcomes, but I think a certain amount of decentralisation, or chaos and disorder if you prefer, does make very large organisations more resilient and less prone to disastrous failure caused by key individuals. "Perfect is the enemy of good enough" often applies in social and political contexts as well as engineering.

That's not how I would describe McNamara's appointment. His job was to massively centralize the DoD and move a bunch of power from the services into the OSD, where it was more answerable to the political branch.

More generally, I agree that there's a certain optimum level of decentralization. I think the US war effort was probably too decentralized (for instance, the lack of any coherent food policy messed up our agricultural efforts), but that doesn't mean that it's impossible to error the other way, and you've picked a good example of a case where the US did exactly that.

Update: A Man and His Ship by Ujifusa doesn't talk too much about it, only noting Gibbs wanted to stick with Liberties and didn't want to change to its replacements (presumably the Victories), and eventually Bernard Baruch got sent in by FDR to be a hatchetman and suggest that Gibbs resign from the WPB. Interesting that it didn't come up.

Weirdly, WWII After WWII just did a blog post where the SS HARRY S. GLUCKMAN came up.

Along with the even weirder case of SS JOHN L. SULLIVAN.

Interesting. I will say that I don't believe ARR was ever in use to try to actually address topweight concerns for safety. It may have been to make ships more comfortable, but no naval architect since Cowper Coles would make a conventional ship dependent on something like that for safety.

Probably the kind of thing you'd only even consider in war and even then it'd be a last resort if you had to modify a ship to be too top heavy.

My father, Wendell H Mixson took command of the newly constructed SS Escanaba Victory and also acted as gunnery officer in June of 1944. In mid Oct.'44, as an essential factor in MacArthur's Return to the Philippines, the SS Escanaba was off loading munitions ashore and came under attack by Japanese Kamakazis as the beginning of Japan's massive battle group began the largest naval battle ever fought: The Battle of Layte Gulf. Following 47 days of grueling combat, The SS Escanaba had repelled and dystoyed numerous Kamakazis attacking that ship or others. The SS Escanaba returned to Honolulu without a stratch.