In 1941, the USN's aviation community was faced with a conundrum. Thousands of new pilots would need to learn the art of taking off from and landing on aircraft carriers, but the previous solution of using an operational carrier would remove a desperately-needed ship from frontline service. Even the new escort carriers, less-capable merchant conversions scheduled to begin entering service in 1942, would be in great demand to fight the Battle of the Atlantic. One enterprising officer came up with a plan to solve this, taking ships and shipbuilding resources otherwise largely useless to the war effort, and turning them into the first decks that thousands of naval aviators would fly from, including future President George H. W. Bush.

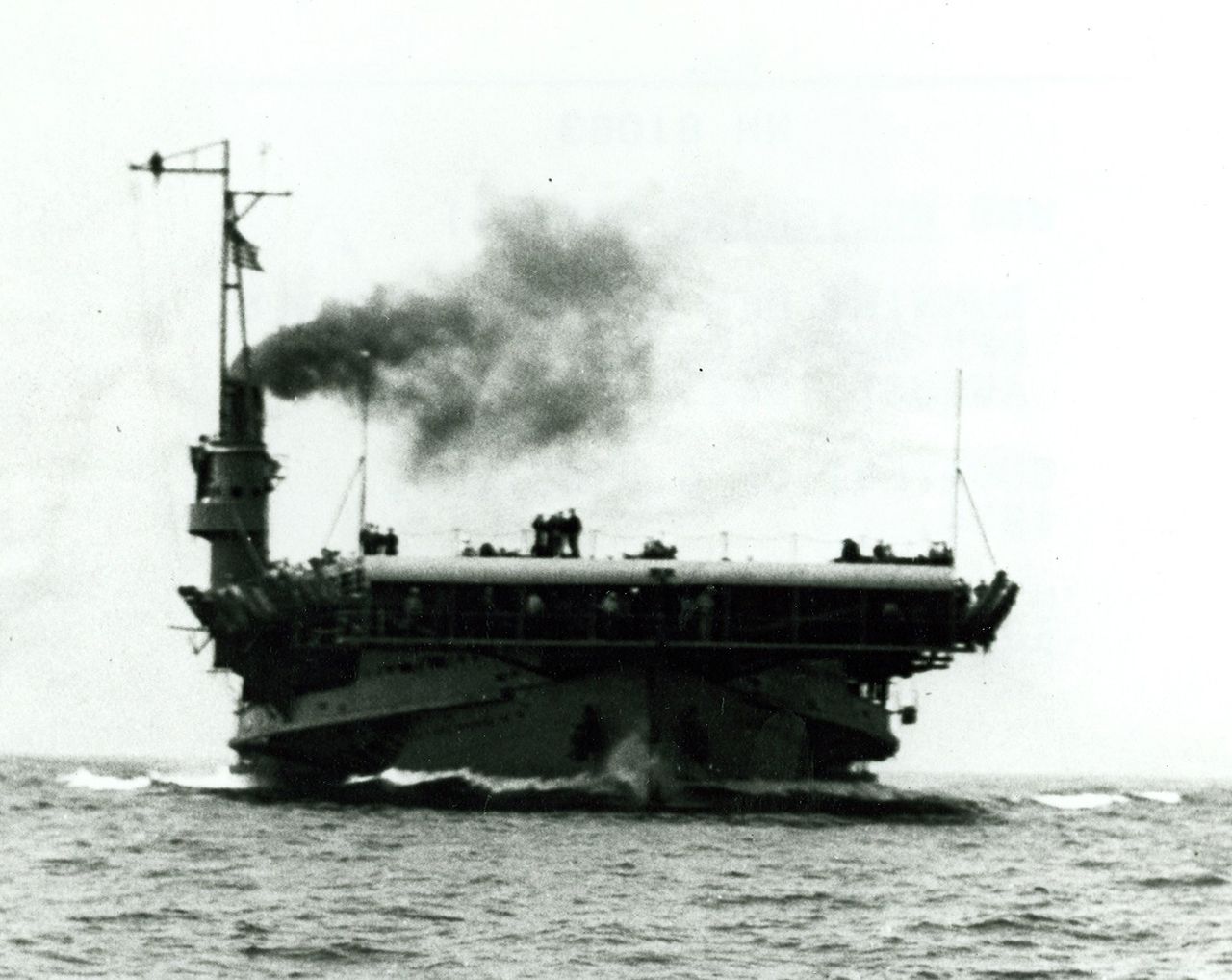

Sable

The plan was simple. Instead of training aviators on the ocean, they would be trained on the Great Lakes. These lakes had long supported a flourishing maritime industry, and while canals did connect them to the ocean, many ships had been built that were too big for the locks.1 A pair of these, the excursion steamers Seeandbee and Greater Buffalo, were to be purchased and quickly fitted with flight decks. The ships that emerged, Wolverine and Sable, were the world's only fresh-water paddle-wheel coal-burning aircraft carriers. Not the only ships with this combination of characteristics, but the only carriers to have any of those traits.2

Wolverine. The outside of the circular paddle wheel housing can be seen

Wolverine’s conversion began in March 1942, and she was commissioned that August before transferring to Chicago to begin training pilots on Lake Michigan the next January. Sable began her overhaul in late 1942, and commissioned in May 1943, going to work almost immediately. Both ships were based at Chicago's Navy Pier, gaining the moniker of the "Corn Belt Navy". The conversions were quite rudimentary, with a simple flight deck and a mock-up island like the ones on combat carriers. The 535' deck was about the same as the deck on an escort carrier, although it was considerably lower to the water. Wolverine’s deck was wood, but Sable had the first metal flight deck in USN service, and tested a number of antiskid coatings for it. She also served as the trials ship for the TDN drone, including the first free takeoff of an unmanned aircraft from a carrier.3 There was no hangar or catapult, which meant that any aircraft damaged on landing would be stuck on deck until the ship returned to port. There was some space to store them forward of the island, but if too many planes were banged up by clumsy students, the carrier would have to return to Chicago immediately.

A TDN-1 aboard Sable

The pace of training kept both carriers very busy. Sable qualified 59 pilots in her first 9 hours of service, while Wolverine's 7,000th deck landing came within 5 months of starting to train pilots. By the end of the war, the Corn Belt Fleet had logged over 120,000 landings and qualified 35,000 pilots. One problem was the low speed of the carriers, which meant that when the winds over Lake Michigan were low, the high-performance aircraft they usually operated couldn't fly. If the backlog of pilots to qualify built up, SNJ Texans, with a much lower stall speed, were used instead, even though most pilots had last flown one months before.

An FM Wildcat that crashed aboard Sable.

Despite the dangers that attended naval aviation at the time, only 200 or so aircraft were lost. This is still enough to make the Great Lakes by far the easiest place to find naval warbird wrecks, and a number have been recovered in recent years.

Wolverine, showing the unusual hull form of the paddle-wheel ship

With the end of the war, there was a surplus of escort carriers available for training and both ships were decommissioned on November 7th, 1945. There was some talk of preserving one as a museum, but the immediate postwar years were notable for their lack of concern for such matters, and both ships were scrapped in 1948, bringing to an end one of the more unique sagas in the history of American naval aviation.

1 This industry built a lot of smaller ships during the war, specializing primarily in submarines and landing craft, although some freighters and a few destroyer escorts were produced. ⇑

2 OK, this isn't 100% true. At least one other carrier, HMS Eagle, burned coal, although she used a mix of oil and coal burning. As far as I'm aware, Wolverine and Sable are still the only carriers to burn only coal. ⇑

3 The TDN was somewhere between a drone and a guided missile, and despite promising trials, it never made it into operational use for reasons I'm not entirely sure of. ⇑

Comments

Amusing...I remember reading about those once before. I was surprised that so many Naval aviators of that time did their first aircraft-carrier flights on a converted paddle-wheel steamer on Lake Michigan.

...Something of a coda to this story - Wolverine and Sable were both converted by the American Shipbuilding Company (later AmShip), where my dad worked from 1965 to when they closed the Lorain OH yard in 1983. As AmShip shrank, almost all of the company's archives were consolidated at the Lorain yard - including the plans for Wolverine and Sable.

Dad was very nearly the guy who turned out the lights at Lorain, and just a few days before it was all over he saw a dumpster being filled with what appeared to be blueprints - it was pretty much everything that AmShip had ever done. It wasn't a great loss for military and commercial ships still in service; their users had complete and in many cases far more updated prints. But the blueprints for Wolverine and Sable's conversions were in there, and Dad knew they had to be saved for history. He and a couple other engineers salvaged them - not sure where they're at now (possibly Bowling Green State University in OH) but they did get rescued.

That's an interesting story. I was kind of hoping it would end with "they're on the wall in my basement". But at least they were saved.

I think some of the early British carriers were coal-fired?

HMS Argus was converted from a partially-built Italian liner (which suggests coal to me), but I can't find evidence either way.

HMS Eagle carried both coal and oil as fuel, having been originally begun as the Chilean battleship Almirante Cochrane (those South American dreadnoughts get everywhere!). I don't know why the Chileans wanted to use both fuels- range because of the length of their coastline?

I do know why the British Hawkins-class cruisers used both coal and oil, as they were designed for extremely long range. One of these was briefly converted into the aircraft carrier HMS Vindictive, but I don't know if this counts as it had separate flying-off and landing decks.

What makes it particularly annoying is that I thought to check for that. I’m pretty sure Argus was oil-burning, because I couldn’t find a mention of coal anywhere near her, but I didn’t think to check Eagle. Probably because I didn’t figure they’d take a step backwards. Well, that’s what footnotes are for.

As for the reasoning behind Eagle using coal, remember that she was laid down in mid-1913, several months before the Revenge class, which were also initially designed for mixed firing. Mixed firing was what they did then. As for the Hawkins, it wasn’t a matter of range, because you get 40% more energy per unit weight out of oil than coal. It was fuel supply. You don’t want to pull a cruiser into port after a long chase and have them say “Yeah, we don’t have any oil for you”. But everyone had coal, so that was what you used.

Good point about the difference between range and fuel supply.

As for the Argus, you are right about it being exclusively oil-fired. Some of the commercial (almost certainly coal-fired) machinery was already there when bought, but was replaced with oil-fired "destroyer-type" boilers.