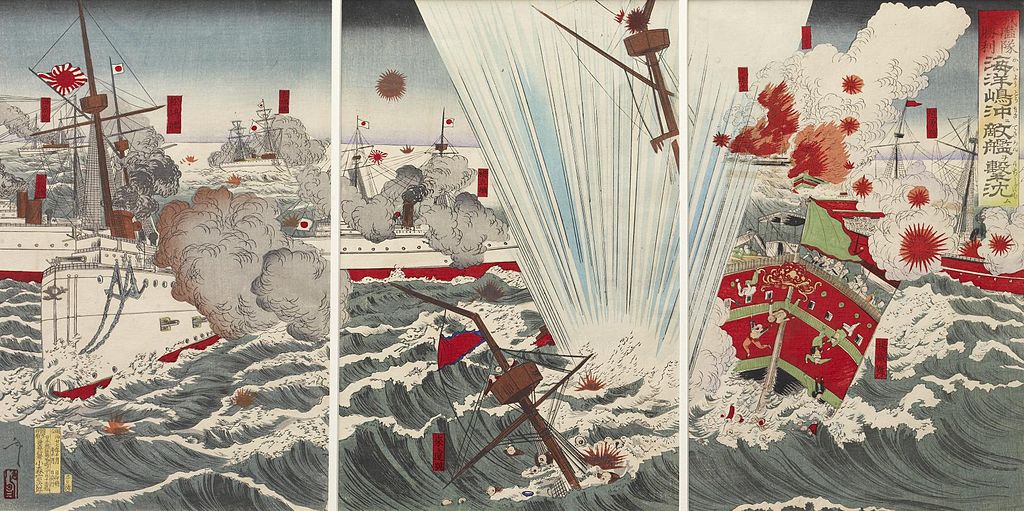

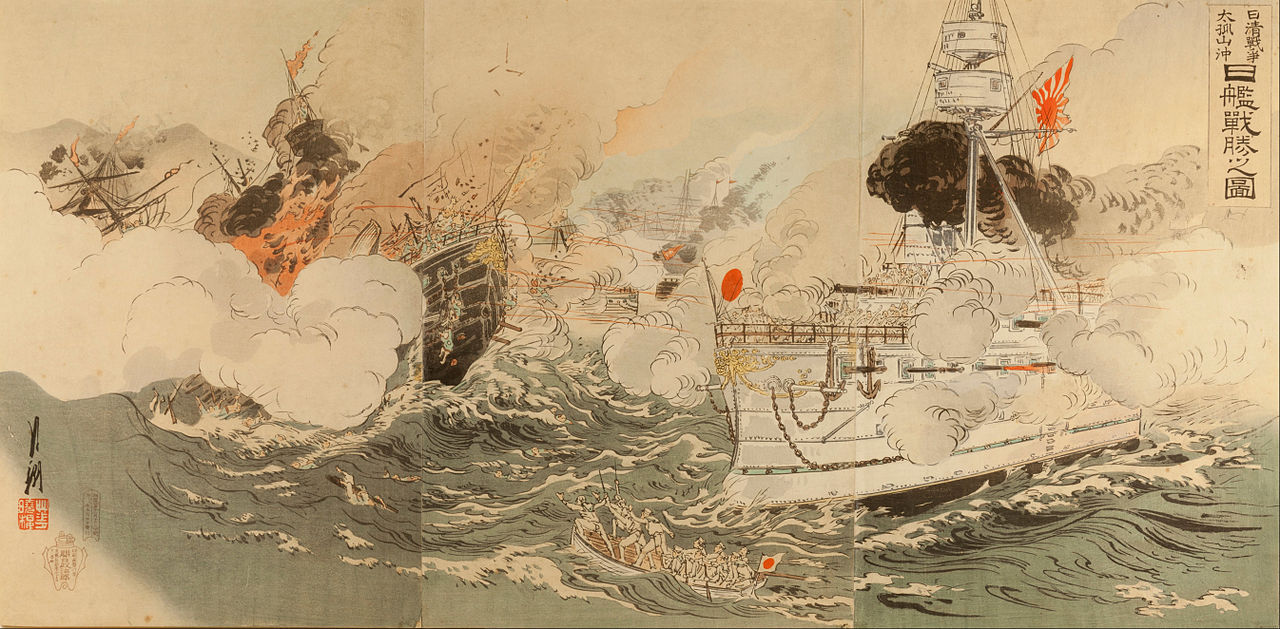

After their victory at Pungdo, the Japanese pursued the Chinese on land, defeating them at Seonghwan. The Chinese response had all the speed and decision that the late Qing Dynasty was famous for, and the Beiyang Fleet spent all of August sitting in port. The Japanese continued to pour troops into Korea, and the Chinese recognized the need to reinforce their garrison, which was only possible by sea. However, they were unable to gather their troops quickly enough to prevent a second defeat at Pyongyang, which drove their forces back to the Yalu River.

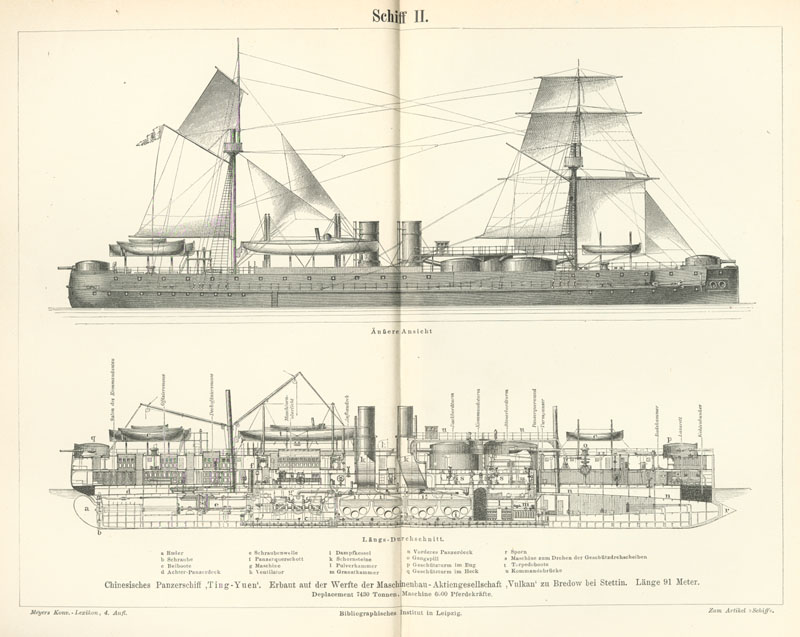

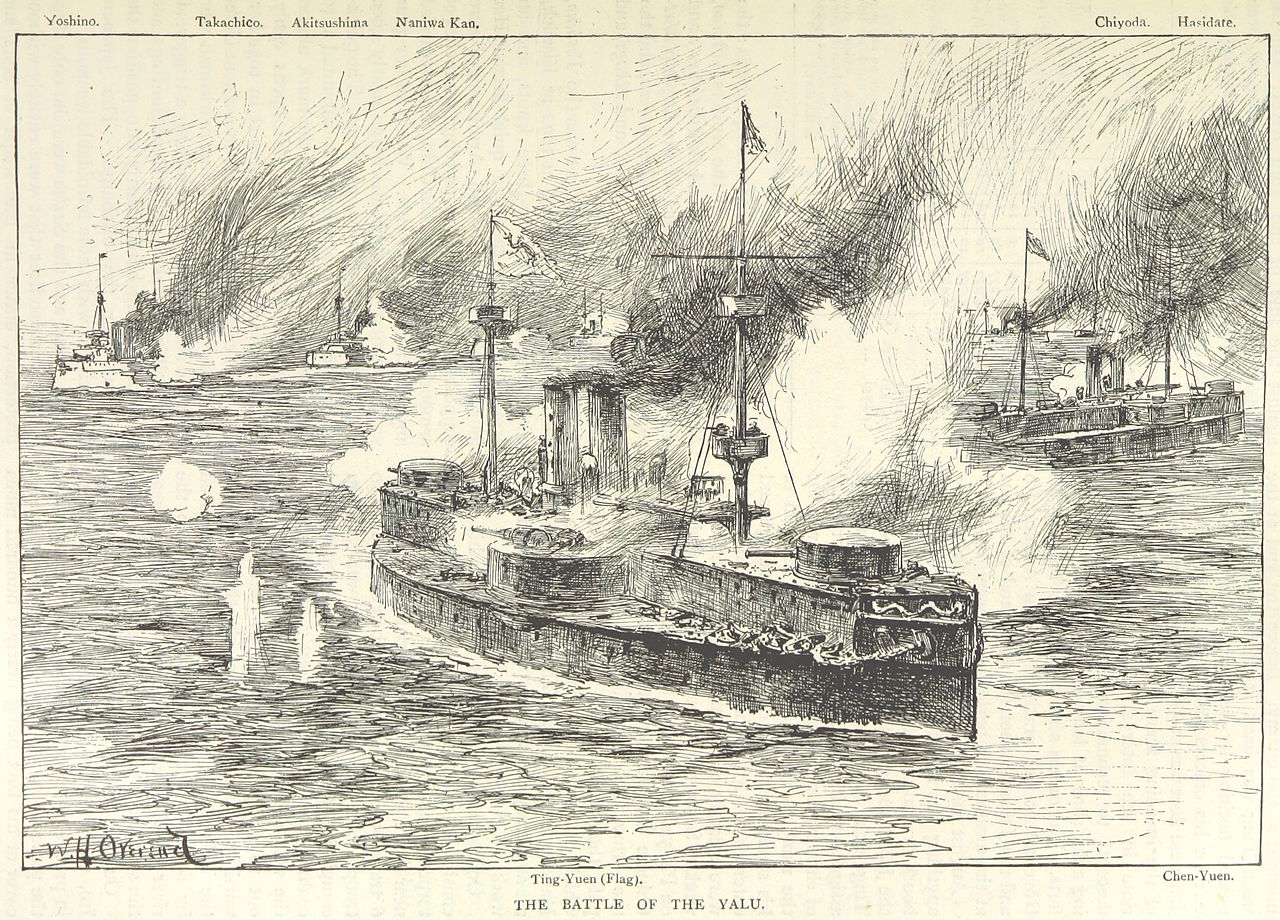

Ding Ruchang, commander of the Beiyang Fleet, had intended to fight the Japanese at sea and defeat their fleet before he took the troops to Korea, but the defeat at Pyongyang forced him to abandon this plan. Instead, he would convoy the troopships with his entire force, which was considerable. His flagship, the ironclad battleship Dingyuan, and her sister Zhenyuan formed the core of his force, supported by three smaller ironclads, five cruisers and four small vessels. The Japanese under Itō Sukeyuki had split their force into two squadrons of four protected cruisers1 each, along with a quartet of support vessels.2

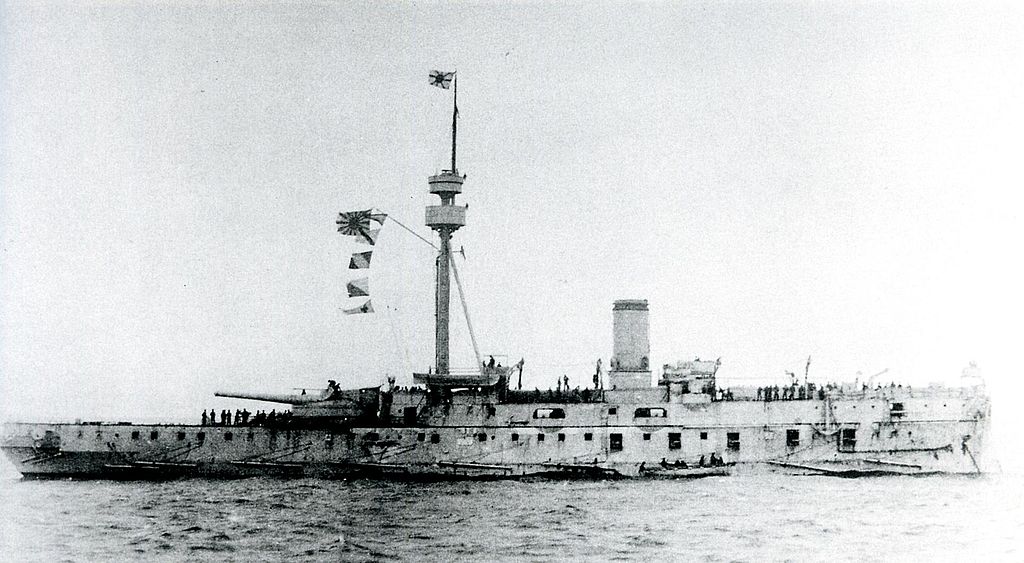

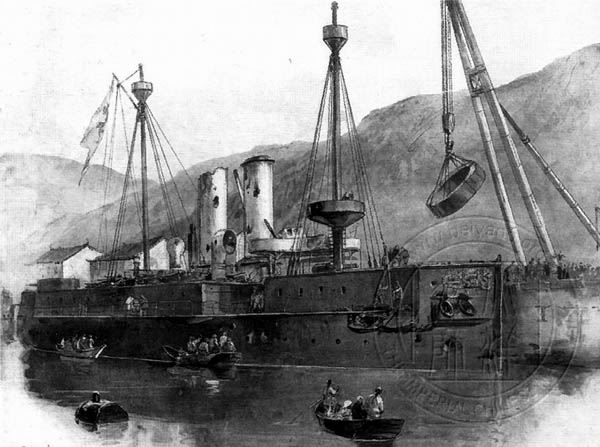

Dingyuan

The Chinese successfully reached the Yalu, and the transports anchored and unloaded overnight. However, the Japanese spotted them there, and began to close. The Chinese fleet got underway, and Ding positioned his forces in a line abreast, with the two battleships in the center. The Chinese had attempted to rectify some of the deficiencies found at Pungdo, reducing flammables and providing extra protection from splinters, but the deeper rot was impossible to tackle in the time available. Possibly the most telling difference between the two fleets was that the Japanese ordered their men fed before battle, while the Chinese didn't bother.

The Chinese line was more like a wedge as a result of poor shiphandling, and the Japanese took advantage, cutting across with their Flying Squadron to strike the Chinese right flank. Dingyuan opened fire with her 12" guns while the Japanese were still well out of range, badly shaking the men on the exposed bridge above. The rest of the Chinese squadron followed suit, while the Japanese held their fire until they reached effective range, counting on their smoke to protect them. Finally, their 4.7" and 6" QF guns opened fire, drenching the Chinese fleet in shells. The armor of the battleships stood up well, but the exposed crew suffered badly, with Dingyuan losing her bridge and signal masts. Admiral Ding was wounded as the bridge collapsed, and had to be taken below. The old cruisers Chaoyong and Yangwei were not so lucky. Both ships quickly caught fire and were forced to withdraw, eventually succumbing to their damage. The Japanese QF guns and their superior crews could fire three or four times as fast as their opponents, and with better accuracy, and the two cruisers were swiftly disabled. The Flying Squadron then reversed course, heading back in front of the Chinese fleet, while the Main Squadron, which had followed the Flying Squadron so far, instead circled the other way, trapping their opponent between two forces.

However, the slower Japaneses vessels at the rear of the squadron had became separated, and found themselves facing their opponents at point-blank range. The ironclad Hiei ended up passing between the enemy battleships, and was saved from destruction only because the Chinese checked fire to avoid hitting each other. The gunboat Akagi and converted passenger liner Saikyo Maru3 suffered even worse damage. Onboard Akagi, a damaged steam pipe blocked the normal route of ammunition supply, forcing an alternate route through an engine-room ventilation shaft to be improvised. Chinese cruisers closed on her, but the timely arrival of the Flying Squadron drove them off, and she managed to make repairs and rejoin the battle.

The Chinese formation disintegrated under the pounding of the Japanese force and the lack of leadership, while the Japanese steamed back and forth on either side, pouring fire into them. The cruisers Zhiyuan and Jingyuan were sunk, and most of the rest of the Chinese ships fled. The Japanese paid a high price, however. The Japanese flagship, Matsushima, was hit by a pair of 12" shells from Zhenyuan. One passed through the ship without detonating, while the other destroyed a 4.7" gun and started a major ammunition fire. The resulting blast and flames killed 57 officers and men, and would have destroyed the ship if not for a few sailors who stuffed their uniforms into the cracks in the magazine bulkhead, blocking the fire from reaching the powder and ammunition. Other crewmen brought the fires under control and even kept fighting the guns, but the damage was severe enough that Admiral Ito was forced to shift his flag to the cruiser Hashidate.

Matsushima

By sunset, the battle was finally petering out. Most of the Chinese ships had fled, badly damaged, with the exception of the battleships. Their 14" belts and 12" barbettes had proven impervious to the Japanese QFs, while the only heavy guns of the Japanese fleet were a few 12.6" Canet guns, which proved incapable of more than 1 round/hour in action. While the Japanese did have torpedoes, neither side's attempts to make use of the new weapons resulted in any hits.4 The Japanese had fired off most of their ammunition, and to have continued the battle after nightfall would have risked the victory they had just won, particularly due to the threat of Chinese torpedo boats.

The battle attracted immediate technical interest as the first large-scale fleet action since Lissa. The power of the QF gun against lightly-armored targets was amply demonstrated, while the performance of the battleships emphasized the need for armor, particularly to the Japanese, who had previously favored lightly-armored gun vessels. Another interesting factor was the role of fire. Almost all of the Chinese vessels caught fire, probably due to poor housekeeping,5 but in most cases the fires were fought effectively and the ships were able to return to action.6

Dingyuan after the battle

Ultimately, the battle ended with five Chinese ships sunk and three badly damaged, 800 sailors dead, and the remaining force withdrawing to Lüshunkou7 for repairs. The Japanese suffered only four ships badly damaged and slightly fewer than 200 men killed. They were lauded for their victory throughout the west, while western advisors to the Chinese, most notably Philo McGiffin, were credited with saving the Beiyang Fleet from total annihilation.8

Yalu River gave the Japanese command of the sea, a command that the Beiyang Fleet would never again dispute. Eventually, the fleet had to be hunted down and destroyed, which will be our story next time.

1 A protected cruiser had no belt, just an armored deck near the waterline to protect magazines and engines. They were generally smaller than armored cruisers. ⇑

2 An interesting statistic is the weight of shell each side could fire in 10 minutes. For the Chinese it was 58,620 lbs, while the Japanese could manage 119,700 lbs. Much of this was due to their extensive use of QF guns, which are credited with 3-4 times the rate of fire of the Chinese guns of a similar caliber. The Chinese had attempted to buy six QF guns for their battleships, but the funds were diverted to the Dowager Empresses's 60th Birthday celebrations. ⇑

3 I'm not entirely sure what Saikyo Maru's role was. Some sources say she was a command ship, others just an armed merchantman. She was carrying an important Admiral, but he wasn't in command of the fleet. ⇑

4 It's possible they didn't attempt to torpedo the battleships because they wished to capture them intact, as they later did with Zhenyuan. ⇑

5 Ships tend to accumulate flammables. During the Solomons Campaign, the USN found that layers of paint were a major fire hazard, and had to be stripped off before going into action. It's possible that the sheer age of the Chinese ships worked against them on that front. ⇑

6 This is also an interesting contrast to the Battle of Santiago three years later. There, the Spanish vessels caught fire very readily, but their crews were unable or unwilling to bring them under control. For all the problems of the Chinese navy, they were probably better than the Spanish. ⇑

7 This port later became famous during the Russo-Japanese war as Port Arthur. ⇑

8 My primary source for this post was Ironclads in Action. It's provided a wealth of information on the actions of the early ironclads, going all the way back to the Lissa post. ⇑

Comments

Were the Chinese battleships suppressed by the non-penetrating damage they took, or was it mostly poor leadership/crew that prevented them from doing more damage?

I think it was more of the latter. AIUI, the ships survived with their physical fighting capability more or less intact, but the crew couldn't/wouldn't fight the ships.

Even for a 32 cm gun how do you make it so that it takes more than an hour to reload?

As best I can tell, the Canet Gun was designed to be the smallest and lightest possible gun of its size. One part of that is a very minimal loading mechanism. So I'd guess they had to manhandle the projectile and powder into the gun, and doing that when you're being shot at, even ineffectively, is not easy.

If I remember correctly from one book I read (which may or may not have been accurate), the rate of fire for the british warships under Francis Drake was something like 2 shots/hour. But they devastated the Spanish armada where the rate was more like 2 shots/day. Picture the muzzle loading cannons along the sides of wooden ships that we all know and love from age-of-sail movies, only this is before they had them mounted on little carriages that rolled back and forth. These are fixed in place. So to muzzle load them, you have to access the muzzle from OUTSIDE the ship.

I'd love to know if this was true, or just a gross exaggeration.

Not quite. Yes, naval cannons of the day didn't have carriages as later guns did. They simply were strapped to a piece of wood, and had to be manhandled for loading. But rates of fire were ludicrously slow back then, and your numbers are probably in the ballpark.

(Age of sail @Doctorpat.)

Average rates of fire, i.e. (total shots fired, which we often know from records of ammunition issued) / (total duration of battle * number of guns), c.1588 do seem to have been about that low, and faster for the English than the Spanish. For the main (Gravelines) 1588 battle, averaged over >= 9-pounder guns, we have values of ~0.4-0.7/hour for a few Spanish ships, and ~1.7/hour for one probably-above-average English ship.

However, such averages can be well below the maximum the weapon is capable of. For example, the equivalent averages for battleship guns are ~10/hour at Tsushima and ~4/hour at Jutland, ~6x and ~30x slower than they were capable of. Similar guns on land could sustain ~6/hour all day battering down fortress walls

One possible reason for below-maximum rates of fire is that most of the crew were busy with something else, with only ~1/gun (~10% of the total) at the heavy guns. The 1500s were a time of transition from sea battles as mostly infantry combat with little damage to the ships themselves, shooting small arms and light ship-mounted guns at enemy crew and often involving boarding actions, to sea battles mostly decided by serious ship damage from heavy guns. In 1588, the Spanish favoured the older form and the English the newer form, and both knew this. Hence, around 70% of the Spanish crews were infantry, while most of the English crews were assigned to the sails to maximize speed and maneuverability, allowing them to avoid being boarded.

One English tactic (explicitly described in the 1617 and 1625 instructions, but probably older) was to approach, fire while turning (each gun firing once, when the turn aimed it at the enemy), and retreat out of effective range to reload. (This is analogous to the countermarch/caracole for land troops, though in Europe the ship version may have come first. The sharp turns with the gunports open were a potential flooding hazard, but I'm not aware of this happening in 1588.)

Later (possibly in 1653), they switched to sailing in straight-ish lines of battle (i.e. not trying to retreat between salvos), with a larger fraction (~50%) of the crew at the heavy guns. This plausibly increased the maximum rate of fire to a broadside every 5-10min, though the existence of multi-day battles between ships that carried ~40 rounds/gun implies that average rates of fire were at least sometimes still as low as ~1/hour. (Rate of fire continued to improve later, to ~2min around 1800 and ~40sec demonstrated (but probably not the norm) in 1838.)

As far as I can find, that was only ever done with breech-loaders. (Yes, the 1500s had those. They didn't take over because they were structurally weak, and hence had to be too low-powered to do much damage.) The English had 4-wheeled gun carriages, visually resembling the 1800s type, by at least 1536 and probably earlier. The Spanish were using 2-wheeled carriages that somewhat resembled a land carriage (but were distinct from their actual land carriages; the Armada was also transporting some land guns for the planned invasion, but not using them as ship guns).

However, these carriages were probably not allowed to recoil into loading position like 1800s ones, but were instead secured in the run-out position when firing. This was probably because, given the limited space implied by having many long guns on a small ship, it was too likely that a gun allowed to recoil would crash into something or someone. (I don't know whether later ships avoided this problem by simply being bigger with less densely packed guns, or whether there was additional innovation involved.)

It seems likely that they were then unhitched after firing and run in by hand. This allowed more control than letting them recoil, so could be done in tighter spaces (including e.g. not having adjacent guns run in at the same time, and/or turning the gun sideways if necessary), but took more time. A modern replica test (in unrealistically easy conditions) found 2.5min for the English type with a crew of 4 and 5min for the Spanish type with a crew of 6.

Alternatively,

It seems well accepted that that was a real thing at least sometimes. It was done by climbing through the gun port and either sitting astride the gun barrel, or for guns that didn't extend far beyond the port, standing on the gunport edge. Turning away and retreating to reload (as mentioned above) would allow this to be done while the gun was facing away from the enemy, and hence without exposing the loader to small arms fire.

However, it's unclear how widespread it was, or why it was being done at all when gun carriages did exist. Some suggest this method was used when needed because there wasn't enough space to run the guns in, and note that most of the evidence for it is from armed merchants (that would want this space for cargo) not dedicated warships. Some suggest it was actually the preferred method, because with so few gun crew, it was faster to have many small teams doing this, than to have a few larger teams each successively run several guns in and out.